Camelot (9 page)

Authors: Colin Thompson

âI think I'm on the King's side,' Sewyr muttered and threw the letter into the lake, where it drifted down to lie on a bed of soft mud and wait for the years to pass until a fictional creature called Gollum would find it and use it to wrap up a Very Important Ring he had found.

As Sewyr had pointed out, her family lived in almost total darkness and were usually covered from

head to foot in unpleasantness. So when she got back to Camelot, she sank the coracle by cutting a big gash in it, rubbed herself in dirt, started talking in a deep voice and pretended she was her twin brother. This meant that one month later when Tyrd would have loaded up his coracle and carried the next month's supply of dried gruel over to the Island of Vegetables, no one did. This meant that Tyrd and the Queen had nothing to eat and because no contact with Camelot was allowed, no one realised. So Tyrd and the Queen starved to death.

42

Meanwhile, Sewyr revealed her true identity to Gerald, who fainted fifteen times until she stopped revealing herself. He then declared his undead love

43

for her and she agreed to marry him. They moved into a delightful home under a wet rock and lived happily ever after, surrounded by seventeen gorgeously malformed one-eyed children and a pet rabbit called Lovely.

Â

Lord Pleat of Perivale was the most reluctant of the Royal Messengers. He was so afraid of travelling â in fact, so afraid of everything â that in order to take as long as possible reaching Wales, Lord Pleat paid someone to steal his horse and got his very helpful squire to drop a very heavy rock on Lord Pleat's right foot. He then dropped an even heavier rock on his very helpful squire. The result was that he had a serious limp and his very helpful squire became less helpful, extremely flat and quite a lot dead.

Hopefully,

he thought as he hopped down the road into the darkness,

dragons will be extinct before I reach the Welsh border, or at the very least someone else will have found a Brave Knight.

What he didn't take into account was that every single passing idiot with a horse and cart would insist on giving him a lift.

âExcuse me, my lord,' they would say as they drew alongside the hopping lord, âI can't help noticing that you've got a bad foot.'

âIndeed.'

âSo, noble lord,' the idiot would continue, âI would consider it a great prilivij, privylodge, um, honour, if you'm would allow me to render you some assisstun, assytunce, some help and give you a lift.'

The idiot would then make his family lie in the back of the cart on top of the cow dung to make a comfortable bed for Lord Pleat to sit on.

âNo, no, my good man, it's fine, thank you,' Lord Pleat would reply. âIt's such a nice day I thought I would take a walk.'

âYou bain't walking. You'm 'oppin'.'

âNo, I'm fine, thank you.'

âAnd it bain't a nice day. It be raining cats and them other things.'

âPotatoes,' the idiot's wife would shout from her bed of dung.

âDogs,' the children would cry.

And the more he insisted he didn't want a lift, the more the idiots thought he did. They picked him up and chucked him in the back of the cart, often missing the human cushions. Quite often these lifts only lasted a few minutes because in the Dark Ages it was against the law for peasants to travel more than

two kilometres from their homes. After he had been chucked into the back of fifteen different carts, Lord Pleat just threw himself into a ditch as soon as he saw or heard anyone coming, which at least washed most of the cow dung off him, though he did keep finding fish in his pockets.

As Lord Pleat lay on his back in the ditch, staring up at the stars in the night sky, they began to fall on him. He was about to cry out when he realised there was no night sky and the stars that were falling were very big snowflakes that soon buried him.

âExcuse me,' said a voice. âAre you going to keep lying on me indefinitely or are you going to move?'

There was someone lying in the ditch beneath him. That would explain the strange warmth he felt in his back.

âAnd another thing,' said the voice. âThis is my ditch and I don't remember inviting you to share it with me.'

Lord Pleat tried to sit up. But the sheer weight of the snow on top of him pinned him down.

âCan't move,' he said. âSorry.'

The person underneath wriggled out and sat

up. It was not, as Lord Pleat had assumed, a smelly old tramp, but a woman who wasn't old or even, considering where she had been lying, that smelly. The woman scraped at the snow until the two of them were sitting facing each other in a sort of igloo.

Ever since he had been born, Lord Pleat of Perivale had been so nervous of women that he had even been shy of his own mother. When he became a teenager it had got even worse. If a pretty girl came within a hundred metres of him, he blushed bright red and began to sweat. It was so bad that he had even thought of becoming a monk so he could go away to a closed monastery where no woman would ever set foot. He would have done so, too, but he had a terrible allergy to religion.

And now here he was closer to a female lady woman person than he had ever been, apart from his own mother, and she was smiling at him, which his mother had never done, and she was taking a handkerchief and wiping the mud away from his face.

He felt himself going faint. Then he stopped feeling faint because he had fainted. It was even worse

when he woke up. He was lying on his back with his head in the female lady woman person's lap and she was stroking his forehead with some wet leaves.

This made him stop being awake because he had fainted again. This happened quite a lot of times until finally he managed to stay awake by staring at a lump of snow above him and pretending it was a cloud.

âFear not, my lord,' said the female lady woman person, âfor I mean you no harm.'

Lord Pleat tried to speak, but no words came out. âThese leaves,' the lady said as she continued to wipe them across his forehead, âare the soothing balm of bladderwrack and purslane and shall calm thy nerves.'

And it worked. Lord Pleat of Perivale felt the fear he had known all his life gradually fade until he was no longer terrified of being so close to a female lady woman person. He found himself not only relaxing, but actually enjoying lying there with his head in her lap.

âWho are you?' he said.

âI am Verdygrys, the Lady of the Ditch,' said the woman.

âSurely you mean the Lady of the Lake?' said Lord Pleat.

âSadly no,' said Verdygrys. âI was up for that job, but my rival placed me under a curse that doomed me to forever live in this ditch far from home and the land I love.'

Lord Pleat of Perivale felt his heart twitter. Not only had this beautiful enchantress charmed away his shyness, she had even filled him with thoughts of love and the incredible idea that he might not have to spend the rest of his life on his own with nothing but his collection of home-made cardboard castles and interesting feathers.

âThere is no curse that cannot be lifted,' he said, blushing bright red, âby love.'

âMy lord,' said Verdygrys, melting into his arms.

And as they kissed the snow melted too, the ditch dried up and the sun came out, which was very strange as it was the middle of the night.

In the Middle Ages, which were also called the Dark Ages, especially at night-time, there was a very

good law which said that no matter what you were doing and who you were doing it for, even the King, if you met your one true love (as long as they weren't from Wales

44

), you could stop doing whatever it was and go home and live happily ever after.

It turned out that Verdygrys was actually Lady Verdygrys of Aquitaine, which was a bit of France, but Lord Pleat of Perivale was in love and prepared to forgive his wife for being anything, even French.

So Lord Pleat of Perivale and Lady Verdygrys of Aquitaine knocked two passing peasants off their horses, which lords were not only allowed but even encouraged to do, mounted up and rode back to Camelot, where they were married and lived happily ever after, except for the bits when they weren't happy, which everyone has. They had seventeen children, which meant most of the time they were far too tired to live happily or unhappily ever after as all they really wanted to do was go to sleep unconsciously ever after.

Â

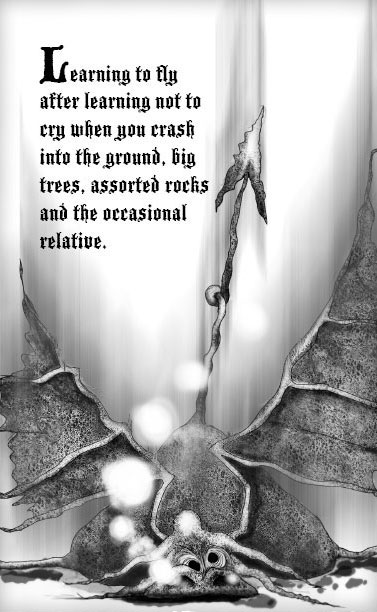

It's hard to imagine that something as big and ungainly as a dragon can fly. All dragons have fat bottoms and short legs so running along like a bird and soaring up into the sky does not come easily to them. Even most young dragons find it hard to imagine they will ever be able to fly.

It's traditional for the father to teach his children flying, while the mother handles the cooking â roasting small animals without frying them to a crisp or getting their hooves stuck up your nose, how to make a delicious pour-over sauce from simple insects, and managing it all without thumbs.

So it was that when Bloat was ten years old, Spikeweed took him to the edge of an extremely tall cliff for his first flying lesson.

âI'm scared, Dad,' said Bloat.

âSo was I,' said Spikeweed. âIt's only natural, son, but believe me, once you've learnt, you'll wonder how you enjoyed life before. Flying is the most exciting thing you can do. It's what us dragons are all about. Just imagine swooping down out of a cloud,

both nostrils blazing fifty-foot flames as a group of terrified pathetic humans run for cover.'

âI suppose,' said Bloat, trying not to look over the edge.

âNo doubt about it, son,' said Spikeweed. âIdiot humans thinking they'll be safe under a big tree, thinking their stupid thumbs will save them. There's nothing like it.'

âBut shouldn't we all try to live together in peace and harmony?' said Bloat, who had been thinking about writing poetry and wondering how he could do it without thumbs.

âRoarin' hippy!' said Spikeweed and pushed his son off the cliff.

Bloat realised very, very quickly that noises coming out of his mouth were not going to help him and as he rolled over and over he looked up and realised his dad wasn't going to help him either. So he began flapping his wings as hard as he could and slowly the ground that had been coming towards

him in a very fast blur began to come into focus and slow down. He would have preferred it to slow down a lot more before he hit it, but he ran out of time.

âNot bad, my boy,' said Spikeweed, landing beside him. âFor a first attempt it was actually pretty good. Only one shattered ankle unless I'm mistaken. That'll soon heal. Why, my first time I killed my Auntie Maud, but then if I hadn't landed on her I suppose I'd have broken more than my kneecaps.'

Bloat lay whimpering quietly to himself until night fell and brought rain. He dragged himself back to the cave and tucked his sore leg under his old great-granny.

But like many things in life, the more you do them, the easier they get. The next time his dad threw him off the cliff, Bloat glided towards the ground like a sack of bricks. The first time he had gone down like a sack with a hundred bricks in it. This time there were twenty and he only broke one of his claws.

The third time there were only three bricks in the sack and he didn't even get a bruise because he landed on Gorella, who had been making one of her rare excursions outside.

After that Bloat threw himself off the cliff without waiting for his dad to do it, and within six months he had even learned how to take off by running along the ground and waving his wings.

When Bloat had fallen on her, Gorella had undergone a strange transformation. Instead of talking to the stain on the cave wall she thought was her dead husband, she thought she was a geography teacher and began swearing at the wall for not doing its homework on the river systems of Brazil. This was more than strange because geography would not be invented for several hundred years.

Bloat's sister, Depressyng, took to flying like a duck takes to water, though at first it was like a roast duck in apple and mushroom sauce. But she was smaller and lighter than her brother so she got fewer broken bones and bruises, and soon the two young dragons were soaring through the skies, dropping unmentionable things on terrified travellers and dribbling down the chimneys of peasants' cottages into the cauldrons of soup they had roasting on their fires.

Â