Caleb's Crossing

For Bizuayehu,

who also made a crossing.

Contents

Anno 1660 Aetatis Suae 15 Great Harbor

He is coming on the Lord’s Day. Though my father…

Once, on a stormy night two winters since, when we…

The account of my fall must begin three years since,…

That summer, perhaps because of the lean winter that had…

He was the younger son of Nahnoso, the Nobnocket sonquem,…

Not long after, Caleb came upon me reading, before I…

I never did ask Caleb if he was the painted…

Who are we, really? Are our souls shaped, our fates…

As it happened, father did propose a journey, around that…

For over an hour, I waited while father attended upon…

The hour is late. It is gone past midnight, so…

Anno 1661 Aetatis Suae 17 Cambridge

I had not thought to take up this pen, having…

I woke in the blueblack predawn, and got right about…

So it went on, day following day, as the weather…

Yester eve, when I wrote of the ordinary daily doings…

This night, I read over what I have set down…

It was like Zuriel’s death, lived a second time. Father…

On the morning of the day he was to sail,…

In the days that followed the discovery of the wreck,…

Not long after, the court formally pronounced the death of…

I decided that night to give my assent to grandfather’s…

I had never seen a set of indentures, and had…

I woke to a clatter of feet above my head,…

Some weeks later, Makepeace sought me out for a private…

I entered the kitchen only to find the room crowded,…

In the event, it was Samuel Corlett who received me.

To say I did not sleep that night would be…

By the time the boy located the midwife and fetched…

But come morning, the school was still on end, roiling…

“You might have consulted me.” Samuel Corlett’s countenance was severe.

I do not pretend to know what would have happened…

Master Corlett called me into his study as the matriculation…

“Name?”

If I had thought to find a more ample providence…

Anno 1715 Aetatis Suae 70 Great Harbor

This morning, light lapped the water as if God had…

I worked for one year in the buttery of Harvard…

The second, and lesser, shadow upon my life that year…

I was right about that, at least. Ammi Ruhama loves…

The boat that brought me home to the island from…

It strikes me now that I have written so little…

I will not say the Harvard commencement of the Year…

I expect that every person alive today has sat with…

When I walked into Caleb’s room, in the home of…

They pulled the Indian College down. It was, you could…

Other Books by Geraldine Brooks

T

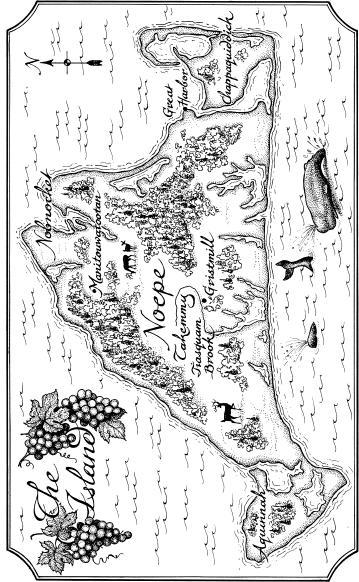

his is a work of imagination, inspired by the life of Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk, a member of the Wôpanâak tribe of Noepe (Martha’s Vineyard), born circa 1646, and the first Native American to graduate from Harvard College.

The character of Caleb as portrayed in this novel is, in every way, a work of fiction. For the facts of Caleb’s life, insofar as they are documented, please see the afterword.

I have presumed to give Caleb’s name to my imagined character in the hope of honoring the struggle, sacrifice and achievement of this remarkable young scholar.

Shown opposite and on the endpapers/inside cover is the only document known to have survived from his hand: a letter, in Latin, to the England-based benefactors who funded his education. In it, Caleb discusses the myth of Orpheus as it relates to his own experience of crossing between two very different cultures.

Anno 1660

Aetatis Suae 15

Great Harbor

H

e is coming on the Lord’s Day. Though my father has not seen fit to give me the news, I have the whole of it.

They supposed I slept, which I might have done, as I do each night, while my father and Makepeace whisper together on the far side of the blanket that divides our chamber. Most nights I take comfort in the low murmur of their voices. But last evening Makepeace’s voice rose urgent and anguished before my father hushed him. I expect that was what pulled me back from sleep. My brother frowns on excessive displays of temperament. I turned on my shakedown then and wondered, in a drowsy way, what it was that exercised him so. I could not hear what my father said, but then my brother’s voice rose again.

“How can you expose Bethia in this way?”

Of course, once I caught my own name that was an end to it; I was fully awake. I raised my head and strained to hear more. It was not difficult, for Makepeace could not govern his tongue, and though I could not make out my father’s words at all, fragments of my brother’s replies were clear.

“Of what matter that he prays? He is only—what is it?—Not yet a year?—removed from paganism, and that man who long had charge of him is Satan’s thrall—the most stiff-necked and dangerous of all of them, as you have said yourself often enough….”

My father cut in then, but Makepeace would not be hushed.

“Of course not, father. Nor do I question his ability. But because he has a facility for Latin does not mean he knows the decencies required of him in a Christian home. The risk is…”

At that moment, Solace cried out, so I reached for her. They perceived I was awake then, and said no more. But it was enough. I wrapped up Solace and drew her to me on the shakedown. She shaped herself against me like a nestling bird and settled easily back to sleep. I lay awake, staring into the dark, running my hand along the rough edge of the roof beam that slanted an arm’s length above my head. Five days from now, the same roof will cover us both.

Caleb is coming to live in this house.

In the morning, I did not speak of what I had overheard. Listening, not speaking, has been my way. I have become most proficient in it. My mother taught me the use of silence. While she lived, I think that not above a dozen people in this settlement ever heard the sound of her voice. It was a fine voice, low and mellow, carrying the lilt of the Wiltshire village in England where she had passed her girlhood. She would laugh, and make rhymes full of the strange words of that place and tell us tales of things we had never seen: cathedrals and carriages, great rivers wide as our harbor, and streets of shops where one who had the coin might buy all manner of goods. But this was within the house, when we were a family. When she went about in the world, it was with downcast eyes and sealed lips. She was like a butterfly, full of color and vibrancy when she chose to open her wings, yet hardly visible when she closed them. Her modesty was like a cloak that she put on, and so adorned, in meekness and discretion, it seemed she passed almost hidden from people, so that betimes they would speak in front of her as if she were not there. Later, at board, if the matter was fit for childish ears, she would relate this or that important or diverting news she had gleaned about our neighbors and how they did. Oft times, what she learned was of great use to father, in his ministry, or to grandfather in his magistracy.

I copied her in this, and that was how I learned I was to loose her. Our neighbor, Goody Branch, who is midwife here, had sent me off to her cottage to fetch more groaning beer, in the hope that it would cool my mother’s childbed fever. Anxious as I was to fetch it back for her, I stood by the latch for some minutes when I heard my mother speaking. What she spake concerned her death. I waited to hear Goody Branch contradict her, to tell her all would be well. But no such words came. Instead, Goody Branch answered that she would see to certain matters that troubled my mother and that she should make her mind easy on those several accounts.