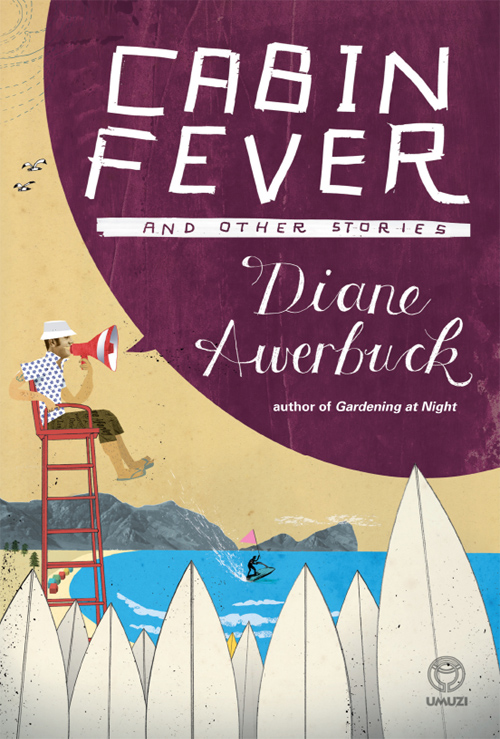

Cabin Fever

A

LSO BY

D

IANE

A

WERBUCK

Gardening at Night

Diane Awerbuck

Published in 2011 by Umuzi

an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Company Reg No 1966/003153/07

80 McKenzie Street, Cape Town 8001, South Africa

PO Box 1144, Cape Town 8000, South Africa

[email protected]

www.randomstruik.co.za

© 2011 Diane Awerbuck

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and recording, or be stored in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN

978-1-4152-0111-4 (Print)

ISBN

978-1-4152-0219-7 (ePub)

ISBN

978-1-4152-0220-3 (

PDF

)

Cover design by Patrick Latimer

Text design by Chérie Collins

Set in 11 on 15 pt Adobe Garamond

For wally whyton

And we’ll go

In and out the windows,

In and out the windows,

In and out the windows,

As we have done before.

8. There is a Light That Never Goes Out

‘L

OOK

,’

HE SAID

,

WHILE SHE WAS STILL

panting behind him on the path. Their shoes had crushed the oils from the fynbos as they went, and the smell settled sharply in her skull so that she remembered being sick as a small child, with her mother propping her up like a doll and rubbing Vicks on her back with warm hands. Her head ached with the tension of holding the past and the present in place.

‘Here.’ He was touching the cliff face.

Trillions of quartz shards were embedded in the rock, shaded from transparent to the deepest brown of the earth, all blinking out from behind his fingers. The girl was sun-struck, wanting to hold his hand. She sat down to free her gritty feet instead, alert to the flapping of his boardshorts. He stood with his back to her, looking at the water, and then he jumped in without waiting.

He surfaced and called back, his voice echoing in the empty space. She shook her head. The water was only warm near the surface: she knew that as soon as her arms or legs sprawled out they would go numb. She thought, People have drowned here. She could see it as if it had already happened – the shout that was equal joy and fear, the boy’s boardshorts billowing out, the flat impact, his body bobbing face-down, the distressed air trapped in the material.

How could he just jump in like that? On the floor of the dam there must be layers and layers of powdery quartz that no light ever reached. When the dam was made that great heart had been uncovered, but it only sank down again slowly in hundreds and thousands, glittering, and recast itself. The secret of the rocks was that they built themselves up again over the centuries. It was impossible to imagine men with machines excavating this place, making space where before there was matter, sinking pylons and pillars to feed the holidaymakers and retirees multiplying like algae over the town below. We have no idea where our water comes from, she thought. There could be anything in it. We just turn on the taps and put our mouths to them.

The water was very dark. The boy looked like he was swimming in Coke: it swirled reddish around his shoulders while his limbs tapered whitely off into points. She watched him stroke out heavily to the other side of the dam, still splashing, taunting her. He hauled himself up and clambered over the old bones of the jetty that sagged into the water. The planks creaked and sighed under his weight. The river changed from red to brown in the dam, and then to green and blue as it ran towards the sea. One day it would take the jetty away with it. When the wind died in gusts at sunset she thought of the wood rotting softly, leaning into the water: in the morning she woke up and wondered if it was gone.

The boy was heading for the jumping rocks, the successive platforms where you threw yourself, screaming, into space. He shrank as he ascended, inserting his fingers into impossible crevices, insinuating his toes. As he went he doubled over his own tracks, starting again from the straining jetty and jumping from higher and higher rocks, keeping his arms tucked close to his ribs so that he entered the water cleanly. He grew bolder, trying to recall the exact places he had jumped from when they were teenagers here in Hermanus, trying to leap back in time. Once he fell backwards and her heart plummeted with him until she understood that it was deliberate. Every time he came up again, whole and alive, replicated. His wet head reappeared, then his chest: he pinwheeled his arms and stretched his red grin at her.

‘The water levels must have changed!’ he called out. ‘See how they’ve dropped here!’ He flung out his arm again and she saw the line of green against the sheer white rock, the residue of childhood summer on this last day of their holiday. The new shallows were endlessly cold, impenetrable.

He kept splashing at her, laughing, so that at last she slipped in and paddled near the edge for a few minutes, avoiding the skeleton of the old pylons that poked out, rusty and jagged. She ducked her aching head under the water and opened her eyes wide, as she always did, searching for whiskery weeds, for anything that might brush curiously against her thigh.

The face that swam briefly up to hers had no lips, no nose or eyes. The small silvery scales that covered it were peeling back, like a second-hand snakeskin handbag, and the hair floating out from the skull was stained rusty red from the tannins in the water.

The girl, without thinking, drew in a shocked mouthful of river water. She felt her throat close in protest: the thought of that water inside her body choked her. She flailed to the surface, trailing bubbles in the murk, and the thing whisked back past her, scales scraping against her hip. She stroked for the side of the dam and tried to push herself back onto the rock face, but it resisted, crumbling in her grip, and she had to force herself out by the power of her biceps, so that she grazed her torso in her panic. She sat on the rock, shivering and hugging her knees while the water streamed off her and flowed back over the rocks into the dam. The hairs on her body tried to stand up in their follicles.

The boy had tired of diving. He swam back and sat next to her for a few minutes while they crouched like rock rabbits and her heart slowed its hammering. I should warn him, she thought, but the walls of her throat felt bruised. She swallowed and began.

‘There was something—’

‘I think—’ he said.

She stopped and deferred to him.

‘You go.’

He fingered a pebble.

‘We’re thinking the same thing.’

She waited, the iron taste of the water coming back up.

‘We should see other people.’

The pebble clinked, given back to the rock.

‘What did you want to say?’

‘Nothing.’

She got up and walked back along the path, alone. The quartz glinted wherever she looked, blinding.

That night she went to bed early, itching in the raw places on her skin, watching the moon with the windows closed so that the baboons wouldn’t get in. She waited to fall into sleep the way the boy had fallen into the dam, happily, trusting that it would be dreamless and ordinary asnd complete, but she couldn’t unclench her fingers from the wakeful cliff. Somewhere outside the house, beyond the mountain scrub, the jetty was leaning out further, slowly splitting its sides.

The bed squeaked as she swung her legs off its edge. She felt her way to the other room with her bare toes, her feet slipping a little in the puddles on the parquet floor.

The watery track soaked reddish into the wood. It led all the way out to the cement patio where they had baked during the day like lizards, lazy and jewelled with sweat, and in the evenings they had watched their meat blistering over the coals.

In the darkness where he had made a humped outline the night before, the boy’s sleeping bag lay empty. She lifted it, ducking down into the sweet smell of his old sleep. She inhaled and held her breath, and she heard the faint effortful dragging sounds outside.

As the creature went it slipped and sighed, its burden sometimes catching fast on the buchu. The scales on its tail twinkled like quartz in the moonlight. The boy’s eyes were blank. When it reached the jetty the last planks disintegrated under its monstrous skittering weight and the creature plopped back into its element, replete. The splinters floated away on the current.

B

RENDA WAS LATE

. S

HE WAS ALWAYS LATE

. Her producers lied to her about the time the recording sessions started so that by the time she turned up, growling and red-eyed, the session musicians had only just arrived and were nodding their heads agreeably at each other, fingers fiddling their instruments: behind them the snare-like windscreen wipers, in front guitar chords soft rain. Brenda would be charmed out of herself, and step neatly into the music. Everyone was happy, including Nicky.

Today was the same, except that they had exactly six hours to film the video. Her song was number one, permeating Nicky’s last summer at home, weaving itself into the weather until it was the sound of the season, of December, of school holidays and lying in the hollows that his body made in the squeaking-hot sand on the beach. Even the white stations were playing it.

Instead of sweeping the stage, Nicky sat where he was hidden by the wings, smoking. Someone on set was playing a beatbox and the chorus floated over to him, squeezing between the dusty black screens. The song played itself over and over, but only in bits: the phantom bootlegger who’d taped it off the radio had tried to wait until the DJ’s intro was finished, but by then Brenda was into the first notes, and they’d given up. Nicky inhaled and jogged his skinny knees as he heard Alex Jay growling, over and over,

Here it is, folks, the tune that’s taking over the townnnnn

. He pictured the man in his cramped studio at night, with his hair peroxided yellow at the tips so that he looked like he’d been shocked. He would be hunched forward, spinning the record until Brenda’s face in the centre merged in on itself, her short ’fro the boundary of her bones.

Nicky popped his jaw and exhaled blue smoke as her voice spooled out over the air, a bright ribbon binding them to the here and now. He wondered what she actually looked like. On the album covers and in the magazines she was changeable, half-princess, half-pug, her hair braided, then shaven, then bleached white like the froth on beer. Brenda was everywhere and nowhere. She cruised the streets with her retinue of bodyguards in black suits,

the boyfriends

, driving a little way behind her in her lowslung red Nissan so they wouldn’t cramp her style. He wondered if she would even say hello to him when she arrived at the studio. Most of all, he wondered what it was like to have a voice like that, to know what it was that you did well. His throat burned.

Nicky stubbed out his cigarette. He was still learning how to hold it properly; his fingers weren’t yellow yet, like Manny’s. He was teaching himself the tricks: how to flip a smoke out of the pack so that it landed between your lips; how to blow rings over people’s heads. Nicky had time on his hands. His friends were in Plett for Matric Rage. They seemed to know exactly what they were going to do in 1984, and all he could think about was that book they’d had to study, the one by Orwell, and that everyone’s future had arrived except his. He expected to find his call-up papers each day that he mooched home from the studio where they had said he could start as a runner. Manny had already been to basic training. He was somewhere up north: everyone just called it The Border.