Bully for Brontosaurus (6 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Evolution is continual change, but not insensibly gradual transition; in any continuum, some points are always more interesting than others. The conventional nomination for most salient point in this particular continuum goes to Alexander Joy Cartwright, leader of a New York team that started to play in Lower Manhattan, eventually rented some changing rooms and a field in Hoboken (just a quick ferry ride across the Hudson), and finally drew up a set of rules in 1845, later known as the New York Game. Cartwright’s version of town ball is much closer to modern baseball, and many clubs followed his rules—for standardization became ever more vital as the popularity of early baseball grew and opportunity for play between regions increased. In particular, Cartwright introduced two key innovations that shaped the disparate forms of town ball into a semblance of modern baseball. First, he eliminated plugging and introduced tagging in the modern sense; the ball could now be made harder, and hitting for distance became an option. Second, he introduced foul lines, again in the modern sense, as his batter stood at a home plate and had to hit the ball within lines defined from home through first and third bases. The game could now become a spectator sport because areas close to the field but out of action could, for the first time, be set aside for onlookers.

The New York Game may be the highlight of a continuum, but it provides no origin myth for baseball. Cartwright’s rules were followed in various forms of town ball. His New York Game still included many curiosities by modern standards (twenty-one runs, called aces, won the game, and balls caught on one bounce were outs). Moreover, our modern version is an amalgam of the New York Game plus other town-ball traditions, not Cartwright’s baby grown up by itself. Several features of the Massachusetts Game entered the modern version in preference to Cartwright’s rules. Balls had to be caught on the fly in Boston, and pitchers threw overhand, not underhand as in the New York Game (and in professional baseball until the 1880s).

Scientists often lament that so few people understand Darwin and the principles of biological evolution. But the problem goes deeper. Too few people are comfortable with evolutionary modes of explanation in any form. I do not know why we tend to think so fuzzily in this area, but one reason must reside in our social and psychic attraction to creation myths in preference to evolutionary stories—for creation myths, as noted before, identify heroes and sacred places, while evolutionary stories provide no palpable, particular object as a symbol for reverence, worship, or patriotism. Still, we must remember—and an intellectual’s most persistent and nagging responsibility lies in making this simple point over and over again, however noxious and bothersome we render ourselves thereby—that truth and desire, fact and comfort, have no necessary, or even preferred, correlation (so rejoice when they do coincide).

To state the most obvious example in our current political turmoil: Human growth is a continuum, and no creation myth can define an instant for the origin of an individual life. Attempts by anti-abortionists to designate the moment of fertilization as the beginning of personhood make no sense in scientific terms (and also violate a long history of social definitions that traditionally focused on the quickening, or detected movement, of the fetus in the womb). I will admit—indeed, I emphasized as a key argument of this essay—that not all points on a continuum are equal. Fertilization is a more interesting moment than most, but it no more provides a clean definition of origin than the most intriguing moment of baseball’s continuum—Cartwright’s codification of the New York Game—defines the beginning of our national pastime. Baseball evolved and people grow; both are continua without definable points of origin. Probe too far back and you reach absurdity, for you will see Nolan Ryan on the hill when the first ape hit a bird with a stone, or you will define both masturbation and menstruation as murder—and who will then cast the first stone? Look for something in the middle, and you find nothing but continuity—always a meaningful “before,” and always a more modern “alter.” (Please note that I am not stating an opinion on the vexatious question of abortion—an ethical issue that can only be decided in ethical terms. I only point out that one side has rooted its case in an argument from science that is not only entirely irrelevant to the proper realm of resolution but also happens to be flat-out false in trying to devise a creation myth within a continuum.)

And besides, why do we prefer creation myths to evolutionary stories? I find all the usual reasons hollow. Yes, heroes and shrines are all very well, but is there not grandeur in the sweep of continuity? Shall we revel in a story for all humanity that may include the sacred ball courts of the Aztecs, and perhaps, for all we know, a group of

Homo erectus

hitting rocks or skulls with a stick or a femur? Or shall we halt beside the mythical Abner Doubleday, standing behind the tailor’s shop in Cooperstown, and say “behold the man”—thereby violating truth and, perhaps even worse, extinguishing both thought and wonder?

THE BRIEF STORY

of Jephthah and his daughter (Judg. 11:30–40) is, to my mind and heart, the saddest of all biblical tragedies. Jephthah makes an intemperate vow, yet all must abide by its consequences. He promises that if God grant him victory in a forthcoming battle, he will sacrifice by fire the first living thing that passes through his gate to greet him upon his return. Expecting (I suppose) a dog or a goat, he returns victorious to find his daughter, and only child, waiting to meet him “with timbrels and with dances.”

Handel’s last oratorio,

Jephtha

, treats this tale with great power (although his librettist couldn’t bear the weight of the original and gave the story a happy ending, with angelic intervention to spare Jephthah’s daughter at the price of her lifelong chastity). At the end of Part 2, while all still think that the terrible vow must be fulfilled, the chorus sings one of Handel’s wonderful “philosophical” choruses. It begins with a frank account of the tragic circumstance:

How dark, O Lord, are thy decrees!…

No certain bliss, no solid peace,

We mortals know on earth below.

Yet the last two lines, in a curious about-face, proclaim (with magnificent musical solidity as well):

Yet on this maxim still obey:

WHATEVER IS, IS RIGHT

This odd reversal, from frank acknowledgment to unreasonable acceptance, reflects one of the greatest biases (“hopes” I like to call them) that human thought imposes upon a world indifferent to our suffering. Humans are pattern-seeking animals. We must find cause and meaning in all events (quite apart from the probable reality that the universe both doesn’t care much about us and often operates in a random manner). I call this bias “adaptationism”—the notion that everything must fit, must have a purpose, and in the strongest version, must be for the best.

The final line of Handel’s chorus is, of course, a quote from Alexander Pope, the last statement of the first epistle of his

Essay on Man

, published twenty years before Handel’s oratorio. Pope’s text contains (in heroic couplets to boot) the most striking paean I know to the bias of adaptationism. In my favorite lines, Pope chastises those people who may be unsatisfied with the senses that nature bestowed upon us. We may wish for more acute vision, hearing, or smell, but consider the consequences.

If nature thunder’d in his op’ning ears

And stunn’d him with the music of the spheres

How would he wish that Heav’n had left him still

The whisp’ring zephyr, and the purling rill!

And my favorite couplet, on olfaction:

Or, quick effluvia darting thro’ the brain,

Die of a rose in aromatic pain.

What we have is best for us—whatever is, is right.

By 1859, most educated people were prepared to accept evolution as the reason behind similarities and differences among organisms—thus accounting for Darwin’s rapid conquest of the intellectual world. But they were decidedly not ready to acknowledge the radical implications of Darwin’s proposed mechanism of change, natural selection, thus explaining the brouhaha that the

Origin of Species

provoked—and still elicits (at least before our courts and school boards).

Darwin’s world is full of “terrible truths,” two in particular. First, when things do fit and make sense (good design of organisms, harmony of ecosystems), they did not arise because the laws of nature entail such order as a primary effect. They are, rather, only epiphenomena, side consequences of the basic causal process at work in natural populations—the purely “selfish” struggle among organisms for personal reproductive success. Second, the complex and curious pathways of history guarantee that most organisms and ecosystems cannot be designed optimally. Indeed, to make an even stronger statement, imperfections are the primary proofs that evolution has occurred, since optimal designs erase all signposts of history.

This principle of imperfection has been a major theme of my essays for several years. I call it the panda principle to honor my favorite example, the panda’s false thumb. Pandas are the herbivorous descendants of carnivorous bears. Their true anatomical thumbs were, long ago during ancestral days of meat eating, irrevocably committed to the limited motion appropriate for this mode of life and universally evolved by mammalian Carnivora. When adaptation to a diet of bamboo required more flexibility in manipulation, pandas could not redesign their thumbs but had to make do with a makeshift substitute—an enlarged radial sesamoid bone of the wrist, the panda’s false thumb. The sesamoid thumb is a clumsy, suboptimal structure, but it works. Pathways of history (commitment of the true thumb to other roles during an irreversible past) impose such jury-rigged solutions upon all creatures. History inheres in the imperfections of living organisms—and thus we know that modern creatures had a different past, converted by evolution to their current state.

We can accept this argument for organisms (we know, after all, about our own appendixes and aching backs). But is the panda principle more pervasive? Is it a general statement about all historical systems? Will it apply, for example, to the products of technology? We might deem this principle irrelevant to the manufactured objects of human ingenuity—and for good reason. After all, constraints of genealogy do not apply to steel, glass, and plastic. The panda cannot shuck its digits (and can only build its future upon an inherited ground plan), but we can abandon gas lamps for electricity and horse carriages for motor cars. Consider, for example, the difference between organic architecture and human buildings. Complex organic structures cannot be reevolved following their loss; no snake will redevelop front legs. But the apostles of post-modern architecture, in reaction to the sterility of so many glass-box buildings of the international style, have juggled together all the classical forms of history in a cascading effort to rediscover the virtues of ornamentation. Thus, Philip Johnson could place a broken pediment atop a New York skyscraper and raise a medieval castle of plate glass in downtown Pittsburgh. Organisms cannot recruit the virtues of their lost pasts.

Yet I am not so sure that technology is exempt from the panda principle of history, for I am now sitting face to face with the best example of its application. Indeed, I am in most intimate (and striking) contact with this object—the typewriter keyboard.

I could type before I could write. My father was a court stenographer, and my mother is a typist. I learned proper eight-finger touch-typing when I was about nine years old and still endowed with small hands and weak, tiny pinky fingers. I was thus, from the first, in a particularly good position to appreciate the irrationality of placement for letters on the standard keyboard—called QWERTY by all aficionados in honor of the first six letters on the top letter row.

Clearly, QWERTY makes no sense (beyond the whiz and joy of typing QWERTY itself). More than 70 percent of English words can be typed with the letters DHIATENSOR, and these should be on the most accessible second, or home, row—as they were in a failed competitor to QWERTY introduced as early as 1893. But in QWERTY, the most common English letter, E, requires a reach to the top row, as do the vowels U, I, and O (with O struck by the weak fourth finger), while A remains in the home row but must be typed with the weakest finger of all (at least for the dexterous majority of right-handers)—the left pinky. (How I struggled with this as a boy. I just couldn’t depress that key. I once tried to type the Declaration of Independence and ended up with: th t ll men re cre ted equ l.)

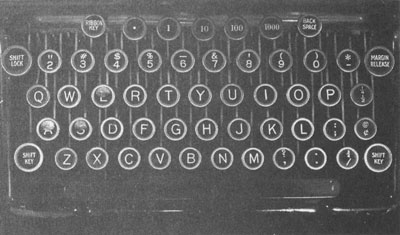

As a dramatic illustration of this irrationality, consider the accompanying photograph, the keyboard of an ancient Smith-Corona upright, identical with the one (my dad’s original) that I use to type these essays (a magnificent machine—no breakdown in twenty years and a fluidity of motion unmatched by any manual typewriter since). After more than half a century of use, some of the most commonly struck keys have been worn right through the surface into the soft pad below (they weren’t solid plastic in those days). Note that E, A, and S are worn in this way—but note also that all three are either not in the home row or are struck with the weak fourth and pinky fingers in QWERTY.

This claim is not just a conjecture based on idiosyncratic personal experience. Evidence clearly shows that QWERTY is drastically suboptimal. Competitors have abounded since the early days of typewriting, but none has supplanted or even dented the universal dominance of QWERTY for English typewriters. The best-known alternative, DSK, for Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, was introduced in 1932. Since then, virtually all records for speed typing have been held by DSK, not QWERTY, typists. During the 1940s, the U.S. Navy, ever mindful of efficiency, found that the increased speed of DSK would amortize the cost of retraining typists within ten days of full employment. (Mr. Dvorak was not Anton of the

New World Symphony

, but August, a professor of education at the University of Washington, who died disappointed in 1975. Dvorak was a disciple of Frank B. Gilbreth, pioneer of time and motion studies in industrial management.)

Since I have a special interest in typewriters (my affection for them dates to childhood days of splendor in the grass and glory in the flower), I have wanted to write such an essay for years. But I never had the data I needed until Paul A. David, Coe Professor of American Economic History at Stanford University, kindly sent me his fascinating article, “Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: The Necessity of History” (in

Economic History and the Modern Economist

, edited by W. N. Parker, New York, Basil Blackwell Inc., 1986, pp. 30–49). Virtually all the nonidiosyncratic data in this essay come from David’s work, and I thank him for this opportunity to satiate an old desire.

The puzzle of QWERTY’s dominance resides in two separate questions: Why did QWERTY ever arise in the first place? And why has QWERTY survived in the face of superior competitors?

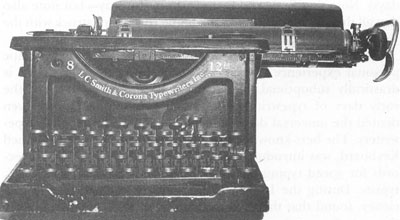

A classic upright typewriter of World War I vintage. Brother to the machine that I use to write these essays.

Notice the patterns of wear for most frequently used keys, as illustrated by breakage through the surface after so many years of striking. In QWERTY, all the most common keys are either not in the home row, or are hit by weak fingers in the home row—thus illustrating the suboptimality of this standard arrangement.

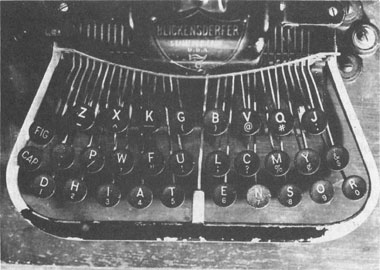

A keyboard for a typewriter made in the 1880’s, illustrating one of the many competing non-QWERTY arrangements so common at the time.

My answers to these questions will invoke analogies to principles of evolutionary theory. Let me, then, state some ground rules for such a questionable enterprise. I am convinced that comparisons between biological evolution and human cultural or technological change have done vastly more harm than good—and examples abound of this most common of all intellectual traps. Biological evolution is a bad analogue for cultural change because the two systems are so different for three major reasons that could hardly be more fundamental.

First, cultural evolution can be faster by orders of magnitude than biological change at its maximal Darwinian rate—and questions of timing are of the essence in evolutionary arguments. Second, cultural evolution is direct and Lamarckian in form: The achievements of one generation are passed by education and publication directly to descendants, thus producing the great potential speed of cultural change. Biological evolution is indirect and Darwinian, as favorable traits do not descend to the next generation unless, by good fortune, they arise as products of genetic change. Third, the basic topologies of biological and cultural change are completely different. Biological evolution is a system of constant divergence without subsequent joining of branches. Lineages, once distinct, are separate forever. In human history, transmission across lineages is, perhaps, the major source of cultural change. Europeans learned about corn and potatoes from Native Americans and gave them smallpox in return.