BROWNING'S ITALY (23 page)

Authors: HELEN A. CLARKE

Frescos by Ghirlandajo abound in Flor-ence in the churches of Santa Maria Novella, Santa Trinita and theOgnissanti, some of them in a good state of preservation and some of them much faded. His finest frescos are

THE ARTIST AND HIS ART 233

perhaps those illustrating the history of St. Francis in Santa Trinita, though the scenes from the lives of the Virgin and St. John the Baptist in Santa Maria Novella are extremely interesting because they contain many por-traits of members of distinguished Florentine families.

In the following stanzas, the poet men-tions a number of painters at whose pictures in Florence we must take glimpses with him. Some of the artists he evidently feels are too near greatness for him to trouble their ghosts with his importunities to lend him a helping hand to find stray specimens of their work.

«

«4

Their ghosts still stand, as I said before,

Watching each fresco flaked and rasped, Blocked up, knocked out, or whitewashed o'er:

— No getting again what the church has grasped! The works on the wall must take their chance;

'Works never conceded to England's thick clime!' (I hope they prefer their inheritance

Of a bucketful of Italian quick-lime.)

When they go at length, with such a shaking

Of heads o'er the old delusion, sadly Each master his way through the black streets taking,

Where many a lost work breathes though badly — Why don't they bethink them of who has merited ?

Why not reveal, while their pictures dree

Such doom, how a captive might be out-ferreted ? Why is it they never remember me ?

"Not that I expect the great Bigordi,

Nor Sandro to hear me, chivalric, bellicose; Nor the wronged Lippino; and not a word I

Say of a scrap of Fra Angelico's: But are you too fine, Taddeo Gaddi,

To grant me a taste of your intonaco, Some Jerome that seeks the heaven with a sad eye ?

Not a churlish saint, Lorenzo Monaco ?

"Could not the ghost with the close red cap,

My Pollajolo, the twice a craftsman, Save me the sample, give me the hap,

Of a muscular Christ that shows the draughtsman ? No virgin by him the somewhat petty

Of finical touch and tempera crumbly — Could not Alesso Baldovinetti

Contribute so much, I ask him humbly ?

"Margheritone of Arezzo,

With the grave-clothes garb and swadling barret (Why purse up mouth and beak in a pet so,

You bald old saturnine poll-clawed parrot ?) Not a poor glimmering Crucifixion,

Where in the f oreground kneels the donor ? If such remain, as is my conviction,

The hoarding it does you but little honor.

There are many of Botticelli's most famous pictures in the galleries in Florence, for example, the wonderful "Coronation of the

THE ARTIST AND HIS ART 235

Virgin" in the Academy of Fine Arts, the "Birth of Venus/' and "Primevera," in the Ufizzi, or there is the fresco of St. Augustine in the Ognissanti. Any or all of these the poet might have had in mind, and it is not surprising that he feit some timidity at approaching the ghost of any one so widely discussed as Botticelli. It is quite true as some one has said that he is the most easily understood of any of the early painters to-day; we might add that only a critic of the era of Maeterlinck could fully appreciate his quali-ties. Symonds does not, but the Vasari editors have summed up his characteristics in an outburst of appreciation which all lovers of Botticelli must approve.

"No one has created so intensely personal a type: the very name of Botticelli calls up to one's mental vision the long, thin face; the querulous mouth with its over ripe lips; the prominent chin sometimes a little to one side; the nose, thin at the root and füll, often almost swollen at the nostrils; the heavy tresses of ocher-colored hair, with the frequent touches of gilding; the lank limbs and the delicately undulating outline of the lithe body, under its fantastically embroidered or semi-trans-parent vesture. This stränge type charms us by its introspective quality, its mournful

4

\;

/

ardor, its fragility, even by its morbidness, and it so charmed the painter that he repro-duced it continually and saw it or certain dis-tinctive features of it in every human creature that he painted. Like all the artists of his time his paganism was somewhat timid and ascetic, his Christianity somewhat paganized and eclectic, but to this fusion of the waning ideals common to all the workers of his age, he added something of his own — a fantas-tic elfin quality as impossible to define as it is to resist. His Madonnas, his goddesses, his saints have a touch of the sprite or the Undine in them. Saint Augustine in his study is a Doctor Faustus who has known forbidden love; his fantastic people of the 'Primevera' have danced in the mystic ring. We feel in his painted folk and his attitude toward them a subtle discord that is at once poignant and alluring, the crowned Madonna dreams somewhat dejectedly in the midst of her glories, and seems rather the mother of Seven Sorrows than a triumphant Queen; the Venus, sailing over the flower-strewn sea is no radiant goddess, but an ansemic, nervous, medieval prüde longing for her mantle; the graces who accompany the bride in the Lemni frescos are highly strung, self-conscious girls, who have grown

THE ARTIST AND fflS ART 237

up in the shadow of the cloister, but to them all Botticelli has lent the same subtle, suggestive charm."

Fiiippino, too, inspires awe in the poet as he well may with his extraordinary frescos in the Santa Maria Novella, which depict many sacred legends with amazing if some-what exaggerated dramatic power; or there are the impressive examples of his work in his earlier manner in the Brancacci chapel of the Carmine; the martyrdom of St. Peter and St. Paul, and St. Paul before the Pro-consul — pictures that rival Masaccio's won-derful frescos in the same chapel. Speaking of Filippino's place in art, the Vasari edi-tors say of him, "He remains the third of the great Florentine trio of Middle Renaissance painters; but while Ghirlandajo and Botticelli were always intensely personal and always developed along the same lines, Fiiippino seems to be three different men at three different times: first the painter of St. Bernard, equaling Botticelli in grace and surpassing him in a certain fervor of feeling, secondly, the painter of the Brancacci frescos, imitating Masaccio, passing beyond him in scientific acquirement, but falling far behind his grand style and last of all, the painter of the cycle of St. Thomas, leaving

behind him his quattro cento charm, still retaining some of his quattro cento awkward-ness, but attaining dramatic composition and becoming a precursor of Raphael."

It seems a little curious that while Browning was calling up so many of these old artists, that he should have omitted to mention Masaccio, who is by general consent con-sidered one of the greatest — the link indeed between Giotto and Raphael. Lafenestre, the art critic, says of him that "he deter-mines anew the destiny of painting by setting it again, but this time strengthened by a perfected technique in the broad straight path which Giotto had opened. In technique he added to art a fuller comprehension of perspective, especially of aerial perspective, the differences in the planes of figures in the same composition. Simplicity and style were both his to such an extent that the Chapel of the Brancacci became a school room to the masters of the fifteenth Century. His color was agreeable, gray and atmos-pheric, his drawing direct and simple/'

Another critic adds to this "He was at once an idealist and a realist, having the merit, not of being the only one to study familiär reality, but of understanding better than any of his predecessors the conditions

THE ARTIST AND HIS ART 239

in virtue of which reality becomes worthy of art.

We may get over the difficulty by imagin-ing that Masaccio was one of those painters between Ghiberti and Ghirlandajo who had not "missed" his "critic meed."

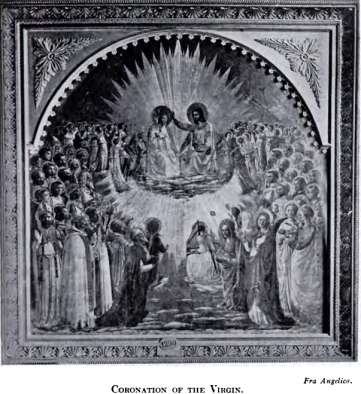

The poet also Stands in some awe of Fra Angelico, who is a figure dwelling apart in the art of the time. Intensely religious by nature, he thought it a sin to paint the nude human figure, consequently his pictures are füll of beings always decorously draped, and with almost naively angelical counte-nances. There is, however, such great charm in his work and such a wonderful spiritual uplift that, with few exceptions, he is the beloved of the critics as well as of the people of his own times and the people of to-day. His place in the evolution of art is so difficult to define that Symonds says of him, he is like a placid and beautiful lake off from the shore of the great river of art that flows from Giotto to Raphael. There are many, indeed most of his pictures are in the galleries in Florence, for the poet to take his fill of. We choose for illustration of his style, not a fresco, but an easel picture, which is regarded by some as his finest work. Lord Lindsay says of this picture in his "Christian Art."

"The Madonna crossing her arms meekly on her bosom and bending in humble awe to receive the crown of heaven, is very lovely, — the Saviour is perhaps a shade less excel-lent: the angels are admirable and many of the assistant saints füll of grace and dignity, but the characteristic of the picture is the flood of radiance and glory diffused over it, the brightest colors — gold, azure, pink, red, yellow, pure, and unmixed, yet harmonizing and blending, like a rieh burst of wind-music, in a manner incommunicable in recital — distinet and yet soft, as if the whole scene were mirrored in the sea of glass that burns before the throne."

The remaining painters whom Browning dares to ask for something are of a distinctly inferior order of genius. Taddeo Gaddi is chiefly famous as the favorite pupil of Giotto, whom he imitates but does not equal in any way, and, furthermore, time has destroyed his frescos and diminished his title to fame by showing him not to be the architect of the Ponta Vecchio, the Ponta Santa Trinita, and not to have helped in the Campanile.

The Poet, himself, very well describes the qualities of Pollajolo. The two brothers — Antonio and Pietro, belonged to the extremely realistic type, and as such had their place in

THE ARTIST AND HIS ART 241

the development of art. Critics have decided they were neither of them great artists. But, in the words of one of these, "The brothers, especially Antonio, were important contribu-tors to the Renaissance movement in the direction of anatomical study." Antonio is accused by Perkins of absence of imagination and affectation of originality, by Symonds of almost brutal energy and bizarre realism. Müntz declares that in his pictures of St. Sebastian, every one of the qualities which make up the Renaissance harmony, rhythm, beauty is outrageously violated. Finally, Lafenestre says he is "frank even to brutality, vigorous even to ferocity, yet his stränge art impresses by its virility."

Antonio like many of the artists of the time was a trained goldsmith, and with him the training developed a taste for anatomy, while in an artist of Botticelli's temperament it developed a taste for delicate ornamentation. In the former instance it resulted in a pre-deiiction for exaggerated and coarse forms; such artists were interested chiefly in con-struction. Over-developed muscles, strained tendons and violent action, recorded with brutal truth were therefore the distinguishing characteristics of their art.

Pictures by these and also the remaining

minor lights were probably examined by Browning in Florence, though his memory here may have dwelt upon two in his own possession which he describes in these stanzas.

Of these minor lights, perhaps the most interest attaches to Margheritone, because he was among the first to show some departure from the Byzantine manner. Crucifix paint-ing was his especial work. His sour expres-sion refers to mixed disdain and despair aroused in him by Giotto's innovations, which made him take to his death-bed in vexation.

One other painter of true distinction is mentioned in the poem, Orcagna.

"This time well shoot better game and bag 'em hot —

No mere display at the stone of Dante, But a kind of sober Witanagemot

(Ex.: 'Casa Guidi/ quod videas ante) Shall ponder, once Freedom restored to Florence,

How Art may return that departed with her. Go, hated house, go each trace of the Loraine's

And bring us the days of Orgagna hither!"

There are wonderful frescos of his in the Santa Maria Novella, among them the Inferno and Paradise suggested by Dante. The beauty and variety in the expressions of his faces is so noticeable a feature of his work that one wonders why Symonds says it can

THE ARTIST AND BIS ART 243

only be discovered after long study. He be-came more impressed with their beauty after examining some tracings, taken chiefly by the Right Hon. A. H. Layard, of these and other frescos of the early masters. He de-clares that by the selection of simple form in outline is demonstrated "not only the grand composition of these religious paintings, but also the incomparable loveliness of their types. How great they were as draughtsmen, how imaginative was the beauty of their con-ception, can be best appreciated by thus artificially separating their design from their coloring. The semblance of archaism dis-appears, and leaves a vision of pure beauty, delicate and spiritual."