Bridge to Terabithia (10 page)

Read Bridge to Terabithia Online

Authors: Katherine Paterson

No!

Something whirled around inside Jess's head. He opened his mouth, but it was dry and no words came out. He jerked his head from one face to the next for someone to help him.

Finally his father spoke, his big rough hand stroking his wife's hair and his eyes downcast watching the motion. “They found the Burke girl this morning down in the creek.”

“No,” he said, finding his voice. “Leslie wouldn't drown. She could swim real good.”

“That old rope you kids been swinging on broke.” His father went quietly and relentlessly on. “They think she musta hit her head on something when she fell.”

“No.” He shook his head. “No.”

His father looked up. “I'm real sorry, boy.”

“No!” Jess was yelling now. “I don't believe you. You're lying to me!” He looked around again wildly for someone to agree. But they all had their heads down except May Belle, whose eyes were wide with terror.

But, Leslie, what if you die?

“No,” he said straight at May Belle. “It's a lie. Leslie ain't dead.” He turned around and ran out the door, letting the screen bang sharply against the house. He ran down the gravel to the main road and then started running west away from Washington and Millsburgâand the old Perkins place. An approaching car beeped and swerved and beeped again, but he hardly noticed.

Leslieâdeadâgirl friendâropeâbrokeâfellâyouâyouâyou

. The words exploded in his head like corn against the sides of the popper.

GodâdeadâyouâLeslieâdeadâyou.

He ran until he was stumbling but he kept on, afraid to stop. Knowing somehow that running was the only thing that could keep Leslie from being dead. It was up to him. He had to keep going.

Behind him came the

baripity

of the pickup, but he couldn't turn around. He tried to run faster, but his

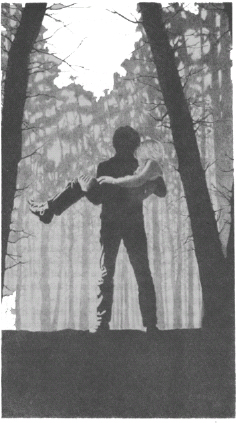

father passed him and stopped the pickup just ahead, then jumped out and ran back. He picked Jess up in his arms as though he were a baby. For the first few seconds Jess kicked and struggled against the strong arms. Then Jess gave himself over to the numbness that was buzzing to be let out from a corner of his brain.

He leaned his weight upon the door of the pickup and let his head thud-thud against the window. His father drove stiffly without speaking, though once he cleared his throat as though he were going to say something, but he glanced at Jess and closed his mouth.

When they pulled up at his house, his father sat quietly, and Jess could feel the man's uncertainty, so he opened the door and got out, and with the numbness flooding through him, went in and lay down on his bed.

Â

He was awake, jerked suddenly into consciousness in the black stillness of the house. He sat up, stiff and shivering, although he was fully dressed from his windbreaker down to his sneakers. He could hear the breathing of the little girls in the next bed,

strangely loud and uneven in the quiet. Some dream must have awakened him, but he could not remember it. He could only remember the mood of dread it had brought with it. Through the curtainless window he could see the lopsided moon with hundreds of stars dancing in bright attendance.

It came into his mind that someone had told him that Leslie was dead. But he knew now that that had been part of the dreadful dream. Leslie could not die any more than he himself could die. But the words turned over uneasily in his mind like leaves stirred up by a cold wind. If he got up now and went down to the old Perkins place and knocked on the door, Leslie would come to open it, P.T. jumping at her heels like a star around the moon. It was a beautiful night. Perhaps they could run over the hill and across the fields to the stream and swing themselves into Terabithia.

They had never been there in the dark. But there was enough moon for them to find their way into the castle, and he could tell her about his day in Washington. And apologize. It had been so dumb of him not to ask if Leslie could go, too. He and Leslie

and Miss Edmunds could have had a wonderful dayâdifferent, of course, from the day he and Miss Edmunds had had, but still good, still perfect. Miss Edmunds and Leslie liked each other a lot. It would have been fun to have Leslie along.

I'm really sorry, Leslie.

He took off his jacket and sneakers, and crawled under the covers.

I was dumb not to think of asking.

S'OK,

Leslie would say.

I've been to Washington thousands of times.

Did you ever see the buffalo hunt?

Somehow it was the one thing in all Washington that Leslie had never seen, and so he could tell her about it, describing the tiny beasts hurtling to destruction.

His stomach felt suddenly cold. It had something to do with the buffalo, with falling, with death. With the reason he had not remembered to ask if Leslie could go with them to Washington today.

You know something weird?

What?

Leslie asked.

I was scared to come to Terabithia this morning.

The coldness threatened to spread up from his

stomach. He turned over and lay on it. Perhaps it would be better not to think about Leslie right now. He would go to see her the first thing in the morning and explain everything. He could explain it better in the daytime when he had shaken off the effects of his unremembered nightmare.

He put his mind to remembering the day in Washington, working on details of pictures and statues, dredging up the sound of Miss Edmunds' voice, recalling his own exact words and her exact answers. Occasionally into the corner of his mind's vision would come a sensation of falling, but he pushed it away with the view of another picture or the sound of another conversation. Tomorrow he must share it all with Leslie.

The next thing he was aware of was the sun streaming through the window. The little girls' bed was only rumpled covers, and there was movement and quiet talking from the kitchen.

Lord! Poor Miss Bessie. He'd forgotten all about her last night, and now it must be late. He felt for his sneakers and shoved his feet over the heels without tying the laces.

His mother looked up quickly from the stove at the sound of him. Her face was set for a question, but she just nodded her head at him.

The coldness began to come back. “I forgot Miss Bessie.”

“Your daddy's milking her.”

“I forgot last night, too.”

She kept nodding her head. “Your daddy did it for you.” But it wasn't an accusation. “You feel like some breakfast?”

Maybe that was why his stomach felt so odd. He hadn't had anything to eat since the ice cream Miss Edmunds had bought them at Millsburg on the way home. Brenda and Ellie stared up at him from the table. The little girls turned from their cartoon show at the TV to look at him and then turned quickly back.

He sat down on the bench. His mother put a plateful of pancakes in front of him. He couldn't remember the last time she had made pancakes. He doused them with syrup and began to eat. They tasted marvelous.

“You don't even care. Do you?” Brenda was watching him from across the table.

He looked at her puzzled, his mouth full.

“If Jimmy Dicks died, I wouldn't be able to eat a bite.”

The coldness curled up inside of him and flopped over.

“Will you shut your mouth, Brenda Aarons?” His mother sprang forward, the pancake turner held threateningly high.

“Well, Momma, he's just sitting there eating pancakes like nothing happened. I'd be crying my eyes out.”

Ellie was looking first at Mrs. Aarons and then at Brenda. “Boys ain't supposed to cry at times like this. Are they, Momma?”

“Well, it don't seem right for him to be sitting there eating like a brood sow.”

“I'm telling you, Brenda, if you don't shut your mouthâ¦.”

He could hear them talking but they were farther away than the memory of the dream. He ate and he chewed and he swallowed, and when his mother put three more pancakes on his plate, he ate them, too.

His father came in with the milk. He poured it carefully into the empty cider jugs and put them

into the refrigerator. Then he washed his hands at the sink and came to the table. As he passed Jess, he put his hand lightly on the boy's shoulder. He wasn't angry about the milking.

Jess was only dimly aware that his parents were looking at each other and then at him. Mrs. Aarons gave Brenda a hard look and gave Mr. Aarons a look which was to say that Brenda was to be kept quiet, but Jess was only thinking of how good the pancakes had been and hoping his mother would put down some more in front of him. He knew somehow that he shouldn't ask for more, but he was disappointed that she didn't give him any. He thought, then, that he should get up and leave the table, but he wasn't sure where he was supposed to go or what he was supposed to do.

“Your mother and I thought we ought to go down to the neighbors and pay respects.” His father cleared his throat. “I think it would be fitting for you to come, too.” He stopped again. “Seeing's you was the one that really knowed the little girl.”

Jess tried to understand what his father was saying to him, but he felt stupid. “What little girl?” He

mumbled it, knowing it was the wrong thing to ask. Ellie and Brenda both gasped.

His father leaned down the table and put his big hand on top of Jess's hand. He gave his wife a quick, troubled look. But she just stood there, her eyes full of pain, saying nothing.

“Your friend Leslie is dead, Jesse. You need to understand that.”

Jess slid his hand out from under his father's. He got up from the table.

“I know it ain't a easy thingâ” Jess could hear his father speaking as he went into the bedroom. He came back out with his windbreaker on.

“You ready to go now?” His father got up quickly. His mother took off her apron and patted her hair.

May Belle jumped up from the rug. “I wanta go, too,” she said. “I never seen a dead person before.”

“No!” May Belle sat down again as though slapped down by her mother's voice.

“We don't even know where she's laid out at, May Belle,” Mr. Aarons said more gently.

Stranded

They walked slowly across the field and down the hill to the old Perkins place. There were four or five cars parked outside. His father raised the knocker. Jess could hear P.T. barking from the back of the house and rushing to the door.

“Hush, P.T.,” a voice which Jess did not know said. “Down.” The door was opened by a man who was half leaning over to hold the dog back. At the sight of Jess, P.T. snatched himself loose and leapt joyfully upon the boy. Jess picked him up and rubbed the back of the dog's neck as he used to when P.T. was a tiny puppy.

“I see he knows you,” the strange man said with a funny half smile on his face. “Come in, won't you.” He stood back for the three of them to enter.

They went into the golden room, and it was just the same, except more beautiful because the sun was pouring through the south windows. Four or five people Jess had never seen before were sitting about, whispering some, but mostly not talking at all. There was no place to sit down, but the strange man was bringing chairs from the dining room. The three of them sat down stiffly and waited, not knowing what to wait for.

An older woman got up slowly from the couch and came over to Jess's mother. Her eyes were red under her perfectly white hair. “I'm Leslie's grandmother,” she said, putting out her hand.

His mother took it awkwardly. “Miz Aarons,” she said in a low voice. “From up the hill.”

Leslie's grandmother shook his mother's and then his father's hands. “Thank you for coming,” she said. Then she turned to Jess. “You must be Jess,” she said. Jess nodded. “Leslieâ” Her eyes filled up with tears. “Leslie told me about you.”

For a minute Jess thought she was going to say something else. He didn't want to look at her, so he gave himself over to rubbing P.T., who was hanging

across his lap. “I'm sorryâ” Her voice broke. “I can't bear it.” The man who had opened the door came up and put his arm around her. As he was leading her out of the room, Jess could hear her crying.

He was glad she was gone. There was something weird about a woman like that crying. It was as if the lady who talked about Polident on TV had suddenly burst into tears. It didn't fit. He looked around at the room full of red-eyed adults.

Look at me,

he wanted to say to them.

I'm not crying.

A part of him stepped back and examined this thought. He was the only person his age he knew whose best friend had died. It made him important. The kids at school Monday would probably whisper around him and treat him with respectâthe way they'd all treated Billy Joe Weems last year after his father had been killed in a car crash. He wouldn't have to talk to anybody if he didn't want to, and all the teachers would be especially nice to him. Momma would even make the girls be nice to him.

He had a sudden desire to see Leslie laid out. He wondered if she were back in the library or in Millsburg at one of the funeral parlors. Would they

bury her in blue jeans? Or maybe that blue jumper and the flowery blouse she'd worn Easter. That would be nice. People might snicker at the blue jeans, and he didn't want anyone to snicker at Leslie when she was dead.

Bill came into the room. P.T. slid off Jess's lap and went to him. The man leaned down and rubbed the dog's back. Jess stood up.

“Jess.” Bill came over to him and put his arms around him as though he had been Leslie instead of himself. Bill held him close, so that a button on his sweater was pressing painfully into Jess's forehead, but as uncomfortable as he was, Jess didn't move. He could feel Bill's body shaking, and he was afraid that if he looked up he would see Bill crying, too. He didn't want to see Bill crying. He wanted to get out of this house. It was smothering him. Why wasn't Leslie here to help him out of this? Why didn't she come running in and make everyone laugh again?

You think it's so great to die and make everyone cry and carry on. Well, it ain't.

“She loved you, you know.” He could tell from Bill's voice that he was crying. “She told me once

that if it weren't for you⦔ His voice broke completely. “Thank you,” he said a moment later. “Thank you for being such a wonderful friend to her.”

Bill didn't sound like himself. He sounded like someone in an old mushy movie. The kind of person Leslie and Jess would laugh at and imitate later.

Boo-hooooooo, you were such a wonderful friend to her.

He couldn't help moving back, just enough to get his forehead off the stupid button. To his relief, Bill let go. He heard his father ask Bill quietly over his head about “the service.”

And Bill answering quietly almost in his regular voice that they had decided to have the body cremated and were going to take the ashes to his family home in Pennsylvania tomorrow.

Cremated.

Something clicked inside Jess's head. That meant Leslie was gone. Turned to ashes. He would never see her again. Not even dead. Never. How could they dare? Leslie belonged to him. More to him than anyone in the world. No one had even asked him. No one had even told him. And now he was never going to see her again, and all they could

do was cry. Not for Leslie. They weren't crying for Leslie. They were crying for themselves. Just themselves. If they'd cared at all for Leslie, they would have never brought her to this rotten place. He had to hold tightly to his hands for fear he might sock Bill in the face.

He, Jess, was the only one who really cared for Leslie. But Leslie had failed him. She went and died just when he needed her the most. She went and left him. She went swinging on that rope just to show him that she was no coward.

So there, Jess Aarons.

She was probably somewhere right now laughing at him. Making fun of him like he was Mrs. Myers. She had tricked him. She had made him leave his old self behind and come into her world, and then before he was really at home in it but too late to go back, she had left him stranded thereâlike an astronaut wandering about on the moon. Alone.

Â

He was never sure later just when he left the old Perkins place, but he remembered running up the hill toward his own house with angry tears streaming down his face. He banged through the door. May

Belle was standing there, her brown eyes wide. “Did you see her?” she asked excitedly. “Did you see her laid out?”

He hit her. In the face. As hard as he had ever hit anything in his life. She stumbled backward from him with a little yelp. He went into the bedroom and felt under the mattress until he retrieved all his paper and the paints that Leslie had given him at Christmastime.

Ellie was standing in the bedroom door fussing at him. He pushed past her. From the couch Brenda, too, was complaining, but the only sound that really entered his head was that of May Belle whimpering.

He ran out the kitchen door and down the field all the way to the stream without looking back. The stream was a little lower than it had been when he had seen it last. Above from the crab apple tree the frayed end of the rope swung gently.

I am now the fastest runner in the fifth grade.

He screamed something without words and flung the papers and paints into the dirty brown water. The paints floated on top, riding the current like a

boat, but the papers swirled about, soaking in the muddy water, being sucked down, around, and down. He watched them all disappear. Gradually his breath quieted, and his heart slowed from its wild pace. The ground was still muddy from the rains, but he sat down anyway. There was nowhere to go. Nowhere. Ever again. He put his head down on his knee.

“That was a damn fool thing to do.” His father sat down on the dirt beside him.

“I don't care. I don't care.” He was crying now, crying so hard he could barely breathe.

His father pulled Jess over on his lap as though he were Joyce Ann. “There. There,” he said, patting his head.

“Shhh. Shhh.”

“I hate her,” Jess said through his sobs. “I hate her. I wish I'd never seen her in my whole life.”

His father stroked his hair without speaking. Jess grew quiet. They both watched the water.

Finally his father said, “Hell, ain't it?” It was the kind of thing Jess could hear his father saying to another man. He found it strangely comforting, and it made him bold.

“Do you believe people go to hell, really go to hell, I mean?”

“You ain't worrying about Leslie Burke?”

It did seem peculiar, but stillâ“Well, May Belle said⦔

“May Belle? May Belle ain't God.”

“Yeah, but how do you know what God does?”

“Lord, boy, don't be a fool. God ain't gonna send any little girls to hell.”

He had never in his life thought of Leslie Burke as a little girl, but still God was sure to. She wouldn't have been eleven until November. They got up and began to walk up the hill. “I didn't mean that about hating her,” he said. “I don't know what made me say that.” His father nodded to show he understood.

Everyone, even Brenda, was gentle to him. Everyone except May Belle, who hung back as though afraid to have anything to do with him. He wanted to tell her he was sorry, but he couldn't. He was too tired. He couldn't just say the words. He had to make it up to her, and he was too tired to figure out how.

That afternoon Bill came up to the house. They were about to leave for Pennsylvania, and he wondered if Jess would take care of the dog until they got back.

“Sure.” He was glad Bill wanted him to help. He was afraid he had hurt Bill by running away this morning. He wanted, too, to know that Bill didn't blame him for anything. But it was not the kind of question he could put into words.

He held P.T. and waved as the dusty little Italian car turned into the main road. He thought he saw them wave back, but it was too far away to be sure.

His mother had never allowed him to have a dog, but she made no objection to P.T. being in the house. P.T. jumped up on his bed, and he slept all night with P.T.'s body curled against his chest.