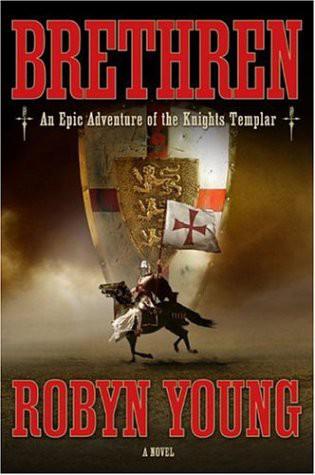

Brethren: An Epic Adventure of the Knights Templar

Read Brethren: An Epic Adventure of the Knights Templar Online

Authors: Robyn Young

BRETHREN

ROBYN YOUNG

DUTTON

DUTTON

Published by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.); Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England; Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd); Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd); Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India; Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd); Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Published by arrangement with Hodder & Stoughton Limited

Published by Dutton, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © 2006 by Robyn Young

All rights reserved

| REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA |

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Young, Robyn, 1975–

Brethren / Robyn Young.

p. cm.

ISBN: 1-4295-4150-4

1. Templars—Fiction. 2. Quests (Expeditions)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3625.O97B74 2006

813'.6—dc22 2006009066

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, thank you, reader, for reading this page when you have no idea who these people are. Just know that without them this book would not be here.

Thanks and love to my mum and dad for all the support over the years. You both made following this dream much easier. Thanks also to the rest of my family, in particular my grandfather, Ken Young, for the stories.

Big thanks to all my friends (you know who you are) for continual encouragement and for helping me to have a life away from my computer, with special thanks to Jo and my second family, Sue and Dave. Much love to fellow writers, Clare, Liz, Niall and Monica, for their invaluable support, emotionally and editorially. Also thanks to my friends and tutors at Sussex University for their excellent guidance and to Sophia for correcting a certain Latin slip.

My gratitude to my agent, Rupert Heath, for the act of faith, tireless, insightful advice, extracting my Yoda-isms and much laughter. Much appreciation to my editor, Nick Sayers, his assistant, Anne Clarke, and the rest of the fantastic team at Hodder & Stoughton for the warm welcome, their enthusiasm and commitment, and Nick’s editorial gems. Thanks also to my American editor, Julie Doughty, at Dutton, for coming in at the eleventh hour with some great suggestions.

Thanks to Amal al-Ayoubi at the School of Oriental and African Studies for checking my Arabic and a huge thank you to Mark Philpott of the Centre for Medieval & Renaissance Studies and Keble College, Oxford for checking the manuscript and saving an amateur from looking too historically challenged. Any mistakes within these pages remain, unfortunately, my own.

Lastly, and most of all, my love to Lee, for all the above and everything else.

From

The Book of the Grail

Brighter than the sun this lake,

Boiling as a cauldron deep,

And though no thing alive could stand

This fiery furnace, molten hot,

Perceval glimpsed creatures there,

Most dark and dreadful to behold.

Writhing beneath the seething surface,

Flames of crimson; amber; gold,

Were things of wing and fang and talon,

As though from the abyss had crawled.

But on the shore there stood a knight,

Adorned in mantle, vestal white,

A red cross on his chest emblazoned,

A holy light around him shining.

To Perceval this knight did turn,

He raised his arm towards the lake,

And in a stern, commanding tone

Bade Perceval cast the treasures in.

Perceval stood still as stone,

His heart went cold, his fingers froze,

He felt he couldn’t bear to throw

The precious treasures from his hands.

Then the knight did speak once more

His voice an arrow driving deep;

We are brothers, Perceval,

Your Brethren would not lead you wrong.

All that is lost will be restored.

All that is dead will live again.

And Perceval, his faith returned,

Did lean and cast the treasures in.

The cross of bright, unalloyed gold

Yellow as the morning sun;

The candlestick of seven prongs

Of beaten silver, shimmering;

Last the crescent of hammered lead

Its rough-hewn surface shadow-dark.

All at once there rose a song

From many voices joined as one.

Borne on a breeze, sweet and pure,

They filled the sky like breaking dawn.

Now the lake was fire no more

But tranquil blue of water clear,

And from it came a man of gold

With silver eyes and lead-black hair.

Perceval fell upon his knees

And wept and wept for utter joy.

He raised his head and thrice aloud,

Hail to thee O Lord!

he cried.

Ayn Jalut (The Pools of Goliath), the Kingdom of Jerusalem

SEPTEMBER

3, 1260

AD

T

he sun was approaching its zenith, dominating the sky and turning the deep ocher of the desert to a bleached bone-white. Buzzards circled the crowns of the hills that ringed the plain of Ayn Jalut and their abrasive cries hung on the air, caught in the solidity of the heat. On the western edge of the plain, where the hills stretched their bare limbs down to the sands, were two thousand men on armored horses. Their swords and shields gleamed, the steel too hot to touch, and although their surcoats and turbans did little to protect them from the sun’s savagery no one spoke of his discomfort.

Mounted on a black horse at the vanguard of the Bahri regiment, Baybars Bundukdari, their commander, reached for the water skin that was fastened to his belt beside two sabers, the blades of which were notched and pitted with use. After taking a draft he rolled his shoulders to loosen the stiffened joints. The band of his white turban was wet with sweat and the coat of mail that he wore beneath his blue cloak felt unusually heavy. The morning was wearing on, the heat gaining in strength, and although the water soothed Baybars’s dry throat it couldn’t quench a deeper thirst that blistered within him.

“Amir Baybars,” murmured one of the younger officers mounted beside him. “Time is passing. The scouting party should have returned by now.”

“They will return soon, Ismail. Have patience.” As Baybars retied the water skin to his belt, he studied the silent ranks of the Bahri regiment that lined the sands behind him. The faces of his men all wore the same grim expression he had seen in many front lines before battle. Soon those expressions would change. Baybars had seen the boldest warriors pale when confronted with a line of enemy fighters that mirrored their own. But when the time came they would fight without hesitation, for they were soldiers of the Mamluk army: the slave warriors of Egypt.

“Amir?”

“What is it, Ismail?”

“We’ve heard no word from the scouts since dawn. What if they’ve been captured?”

Baybars frowned and Ismail wished he had remained silent.

On the whole, there was nothing particularly striking about Baybars; like most of his men he was tall and sinewy with dark brown hair and cinnamon skin. But his gaze was exceptional. A defect, which appeared as a white star in the center of his left pupil, gave his stare a peculiar keenness; one of the attributes that had earned him his sobriquet—the Crossbow. The junior officer Ismail, finding himself the focus of those barbed blue eyes, felt like a fly in the web of a spider.

“As I said, have patience.”

“Yes, Amir.”

Baybars’s gaze softened a little as Ismail bowed his head. It wasn’t many years ago that Baybars himself had waited in the front line of his first battle. The Mamluks had faced the Franks on a dusty plain near a village called Herbiya. He had led the cavalry in the attack and within hours the enemy was crushed, the blood of the Christians staining the sands. Today, God willing, it would be the same.

In the distance, a faint twisting column of dust rose from the plain. Slowly, it began to take the shape of seven riders, their forms distorted by the rippling heat haze. Baybars kicked his heels into the flanks of his horse and surged out of the ranks, followed by his officers.

As the scouting party approached, riding fast, the leader turned his horse toward Baybars. Pulling sharply on the reins he came to a halt before the commander. The beast’s tan coat was stained with sweat, its muzzle flecked with foam. “Amir Baybars,” panted the rider, saluting. “The Mongols are coming.”

“How large is the force?”

“One of their toumans, Amir.”

“Ten thousand. And their leader?”

“They are led by the general, Kitbogha, as our information suggested.”

“They saw you?”

“We made certain of it. The advance isn’t far behind us and the main army follows them closely.” The patrol leader trotted his horse closer to Baybars and lowered his voice, so that the other officers had to strain to hear him. “Their might is great, Amir, and they have brought many engines of war, yet our intelligence suggests it is but one-third of their army.”

“If you cut off the head of the beast, the body will fall,” replied Baybars.

The strident wail of a Mongol horn sounded in the distance. Others quickly joined it until a shrill, discordant chorus was ringing across the hills. The Mamluk horses, sensing the tension in their riders, began to snort and whinny. Baybars nodded to the leader of the patrol, then turned to his officers. “On my signal sound the retreat.” He motioned to Ismail. “You will ride with me.”

“Yes, Amir,” replied Ismail, the pride clear in his face.

For ten, twenty seconds the only sounds that could be heard were the distant horns and the restless sighing of the wind across the plain. A pall of dust cloaked the sky in the east as the first lines of the Mongol force appeared on the ridges of the hills. The riders paused briefly on the summit and then they came, flowing onto the plain like a sea of darkness, the flash of sunlight on steel glittering above the black tide.

Behind the advance came the main army, led by light-horsemen wielding spears and bows, and then Kitbogha himself. Flanking the Mongol leader on all sides were veteran warriors, clad in iron helms and lamellar armor fashioned from sheets of rawhide, bound with strips of leather. Each man had two spare horses and behind this thundering column rolled siege engines and wagons laden with the riches pillaged in the Mongols’ raids on towns and cities. The wagons were driven by women who carried great bows upon their backs. The Mongols’ founder, Genghis Khan, had died thirty-three years ago, but the might of his warrior empire lived on in the force that now faced the Mamluks.

Baybars had been anticipating this confrontation for months, but his hunger for it had gnawed at him for much longer. Twenty years had passed since the Mongols had invaded his homeland, ravaging his tribe’s lands and livestock; twenty years since his people had been forced to flee the attack and request the aid of a neighboring chieftain who had betrayed them and sold them to the slave traders of Syria. But it wasn’t until several months ago, when a Mongol emissary had arrived in Cairo, that an opportunity for Baybars to seek revenge upon the people who had precipitated his delivery into slavery had arisen.

The emissary had come to demand that Kutuz, the Mamluk sultan, submit to Mongol rule and it was this imposition, above and beyond the Mongols’ recent devastating assault on the Muslim-ruled city of Baghdad, that had finally spurred the sultan to act. The Mamluks bowed to no one except Allah. While Kutuz and his military governors, Baybars included, had set about planning their reprisal, the Mongol emissary had had a few days to reflect upon his mistake buried up to his neck in sand outside Cairo’s walls, before the sun and the buzzards had finished their work. Now Baybars would teach a similar lesson to those who had sent him.

Baybars waited until the front lines of the heavy cavalry were halfway across the plain, then wheeled his horse around to face his men. Drawing one of his sabers from its scabbard he thrust it high above his head. Sunlight caught the curved blade and it shone like a star.

“Warriors of Egypt,” he shouted. “Our time is now at hand and with this victory we will build of our enemy a pile of corpses that will be higher than these hills and wider than the desert.”

“To victory!” roared the soldiers of the Bahri regiment. “In the name of Allah!”

As one, they turned from the approaching army and urged their horses toward the hills. The Mongols, thinking their enemy was fleeing in terror, whooped as they gave chase.

The western line of hills that bordered the plain was shallow and broad. A cleft divided them, forming a wide gorge. Baybars and his men plunged through this opening, riding furiously, and the first riders of the Mongol advance came charging through the clouds of dust that choked the air in the wake of the Mamluk horses. The main Mongol army followed, funneling through into the gorge, causing loose rock and sand to shower down from the hillsides with the tremor of their passing. The Bahri regiment, at a signal from Baybars, reined in their horses and turned, forming a barrier to block the Mongols’ approach. Suddenly, the blare of many horns and the cacophonous thudding of kettledrums echoed through the gully.

A figure, dark against the glare of the sun, had appeared on one of the ridges above the gorge. The figure was Kutuz. He was not alone. With him on the ridge, poised above the valley floor, were thousands of Mamluk soldiers. The cavalry, many of them archers, were ranked in sections of color, marking the various regiments: purple; scarlet; orange; black. It was as if the hills wore a vast patchwork cloak that was threaded with silver wherever spearheads or helms caught the light. Infantry waited bearing swords, maces and bows, and a small but deadly corps of Bedouin and Kurdish mercenaries flanked the main force in two wings, bristling with seven-foot-long spears.

Now that the Mongols were caught in Baybars’s trap all he had to do was tighten the noose.

After the sounding of the horns came a war cry from the Mamluks, the roar of their combined voices drowning, momentarily, the kettledrums’pulse. The Mamluk cavalry charged. Some horses fell on the descent in a billow of dust, the cries of riders lost in the ground-shuddering thunder of hooves. Many more hurtled toward their targets as two Mamluk regiments swept onto the plain of Ayn Jalut to herd the last of the Mongol forces into the passage. Baybars swung his saber above his head and yelled as he charged. The men of the Bahri regiment took up his cry.

“Allahu akbar! Allahu akbar!”

The two armies met in a storm of dust and screams and the clang of steel. In the first seconds, hundreds from both sides went down and the dead clogged up the ground, making treacherous footing for those left standing. Horses reared, throwing their riders into the chaos and men shrieked as they died, spraying the air with blood. The Mongols were renowned for their horsemanship, but the passage was too narrow for them to maneuver effectively. Whilst the Mamluks drove relentlessly into the main body of the army, a line of Bedouin cavalry prevented the Mongol advance from outflanking them. Arrows hissed down from the hillsides and once in a while an orange ball of flame would explode across the melee as the Mamluk troops hurled clay pots filled with naphtha. The Mongols hit by these missiles flamed like torches, screaming hideously as their horses ran wild, spreading fire and confusion through the ranks.

Baybars swung one of his sabers in a vicious arc as he swept into the fray, taking a man’s head clean from his shoulders with the momentum of the blow. Another Mongol, face splattered with the blood of his fallen comrade, took the dead man’s place immediately. Baybars lashed out with his blades as his horse was knocked and jostled beneath him and more and more men poured into the turmoil. Ismail was at Baybars’s side, drenched in blood and shrieking as he thrust his sword through the visor of a Mongol’s helm. The blade stuck fast for a moment, buried in the man’s skull, before the officer wrenched it free and searched for another target.

Baybars’s sabers danced in his hands, two more warriors falling under his hammering blows.

Kitbogha, the Mongol general, was fighting savagely, swinging his sword in tremendous haymaker strokes that were cleaving skulls and tearing limbs and even though he was surrounded no one seemed able to touch him. Baybars’s thoughts were on the bounty that awaited the man who captured or killed the enemy lord, but a wall of fighting and a hedge of arcing blades blocked his path. He ducked as a feral youth rushed him, whirling a mace, and forgot about Kitbogha as he concentrated on staying alive.

After the first lines had fallen or been beaten back, Mongol women and children were fighting alongside the men. Although the Mamluks knew that the wives and daughters of the Mongol men fought in battle, it was a sight, nonetheless, that caused some to falter. The women, with their long, wild hair and snarling faces, fought just as well as and perhaps even more fiercely than the men. A Mamluk commander, fearing the effect on the troops, raised his voice above the din and sent out a rallying cry that was soon taken up by others. The name of Allah filled the air, reverberating off the hills and ringing in the ears of the Mamluks, as their arms found new strength and their swords new purchase. Any compunction was lost in the heat of battle and the Mamluks cut through all those who stood against them. To the slave warriors, the Mongol army had become an anonymous beast, ageless and sexless, that had to be taken piece by piece if it were to perish.

Eventually, the sword strokes grew sluggish. Men, unhorsed and locked together in combat, leaned on one another for support as they parried each blow. Groans and cries were punctuated by screams as swords found slowing targets. The Mongols had led a final storm against the infantry, hoping to break through the barrier and ride in behind the Mamluks, but the foot soldiers held their ground and only a handful of the Mongol cavalry had penetrated the line of spears. They had been met by Mamluk riders and were dispatched instantly. Kitbogha had gone down, his horse pulled over by the sheer press of men around him. Victorious, the Mamluks had severed his head and flaunted it before his broken forces. The Mongols, who had been called the terror of nations, were losing. But, more important, they knew it.

Baybars’s horse, pierced in the neck by a stray arrow, had thrown him and bolted. He fought on foot, his boots slick with blood. The blood was everywhere. It was in the air and in his mouth, it was dripping through his beard and the hilts of his sabers were slippery with it. He lunged forward and hacked at another man. The Mongol slumped to the sand with a cry that ceased abruptly and when no one took his place Baybars paused.

Dust had obscured the sun and turned the air yellow. A gust of wind scattered the clouds and Baybars saw, flying high above the Mongols’ carts and siege engines, the flag of surrender. Looking around him, all he could see were piles of bodies. The reek of blood and opened corpses was thick on the air and already the carrion eaters were shrieking their own triumph in the skies above. The fallen lay sprawled across one another, and among the leather breastplates of the enemy were the bright cloaks of the Mamluks. In one pile, close by, Ismail lay on his back, his chest cleaved by a Mongol sword.