Breaking Stalin's Nose (2 page)

Read Breaking Stalin's Nose Online

Authors: Eugene Yelchin

I WAKE UP in the middle of the night, worried. Why did he say “Anything ever happens to me, go to Aunt Larisa”? I don't understand. What could happen to him?

I watch the faint shades of the falling snow slide across the ceiling, listening to his even breathing. After a while, I feel better. Nothing could happen to my dad; Stalin needs him.

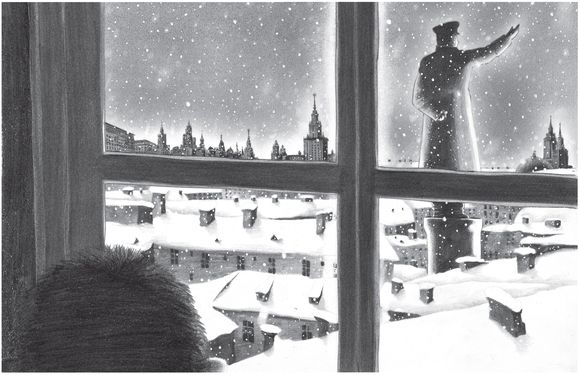

I turn to the window, where a giant statue of Stalin gleams under searchlights. The statue is made from the steel of fighter planes and stands taller than any building. You can see it from every window in Moscow.

Recently, my dad caught a gang of wreckers scheming to blow it up. Wreckers are enemies of the people and want to destroy our precious Soviet property. I can't imagine anybody who would dare to damage a monument to Comrade Stalin, but there are some bad characters out there. Obviously, they're always caught.

I stare at the statue and pretend it is Comrade Stalin himself, watching over Moscow from his great height. His steady eyes track a legion of shiny black dots zipping up and down the snow-white streets. The dots grow larger and larger, until they turn into shiny black automobiles made of black metal and bulletproof glass. These beautiful machines belong to our State Security. I know

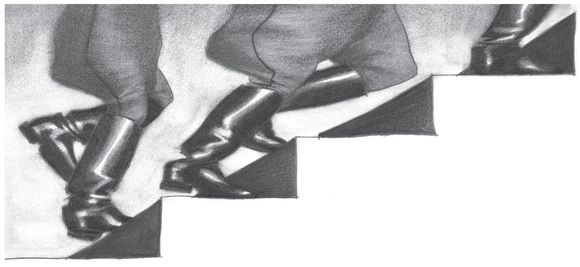

because my dad has one. Night after night, Stalin's urgent orders drive these automobiles past our house, but tonight one turns into our courtyard. I listen to the engine left running, doors slamming, and boots hurrying up the stairs. Then the doorbell rings.

because my dad has one. Night after night, Stalin's urgent orders drive these automobiles past our house, but tonight one turns into our courtyard. I listen to the engine left running, doors slamming, and boots hurrying up the stairs. Then the doorbell rings.

This is how we know who has visitorsâwe count the rings. One for the Shulmans, two for the Ivanovs, three for the Stukachovs, four for the Kozlovs, five for us, and so on, all the way to the Lodochkins, who get twelve.

Ring, ring, ring, ring, ring.

Five. They want us.

Ring, ring, ring, ring, ring.

“Dad, Dad, a car for you. On Stalin's orders!”

Ring, ring, ring, ring, ring.

He sits up, wrapped in the sheet like a ghost, glares at me wildly, and says, “Stay in bed.”

I wait till he leaves, then go after him into the kitchen. What I see in the dull glow of the room is the white sheet, taut and sweaty over his back. The front door is open; he's leaning out, listening to someone on the other side. When he finally turns, he has a face I've never seen before.

“What's wrong, Dad?”

Out of the darkness, three large figures in State Security uniforms stomp into the kitchen. They follow my dad past where I'm standing and into the corridor toward our room. The last in line catches his cap against the laundry line, picks it up, swears,

and clomps after the rest. All this noise in the middle of the night, but our neighbors' doors stay shut. Nobody looks out to complain.

and clomps after the rest. All this noise in the middle of the night, but our neighbors' doors stay shut. Nobody looks out to complain.

When I get to the room, Dad is sitting on the floor, holding his ear. The officer's leather belt creaks as he turns to look at me, his eyes bloodshot. “Nothing to worry about, little boy,” he says in a hoarse voice. “A friendly chat, that's all.”

The guards pull out the drawers and dump our things on the floor. They shake loose pages out of our books. They cut up Dad's mattress and feel inside it. They tap on the walls, listening for hidden places, and open part of the floor where the nails are loose. Soon what we have is in a pile, torn and wrecked. The only thing they don't touch is a framed picture of Stalin. But they look behind it.

My dad is still pulling on a shirt when the guards yank him out of the room. I grab his arm and hang on to him as tight as I can. This close, I see his ear is bleeding. “It's more important to join the Pioneers

than to have a father,” he whispers hurriedly. “You hear me?”

than to have a father,” he whispers hurriedly. “You hear me?”

“No talking,” orders the officer in his scratchy voice. “Move on.” He shoves me aside.

In the corridor stands our neighbor Stukachov. “It's me, Stukachov. I made the report,” he says, smiling and bobbing his head at the passing uniforms.

“Comrade Stalin appreciates your vigilance, citizen,” says the officer, and without looking at Stukachov, he pushes on, my dad's briefcase under his arm. Then all of us togetherâthe officer, the guards, my dad, Stukachov, and me, closing the rearâmarch down the corridor to the dimly lit kitchen. I notice we are walking in step. Left, right, left, right, left, right, like on parade.

“Comrade Senior Lieutenant?” calls Stukachov. “Regarding the boy?”

“The state will bring him up,” says the officer. “They'll collect him first thing in the morning.”

“Wise,” Stukachov says. “We'll be moving in, then?”

The officer doesn't answer. Stukachov halts and I bump into him, and by the time I loop around and reach the front door, they are trotting down the steps.

“Dad! Dad! Wait!”

The officer spins and slams the front door shut with such force, I have to pull back fast so it won't smash my face. I try opening it, but the lock is jammed. I kick and kick, but the door won't budge. I dart to the window. Down below, the guards shove my dad into the car and slam the door. The engine revs up, tires spin in the snow, and, when the car leaps forward, the headlights blast across the windows. The icy glass before me flares up, turning white. When it's clear again, the courtyard is empty.

SOON THE COURTYARD turns blurry, warped at the edges. I rub at my eyes and my knuckles come away wet. Then I hear a broom sweeping the floor somewhere. I turn and listen. It's coming from our room.

When I get there, the door is open. Stukachov's wife is in our room, sweeping. What a good woman, rising from her sleep, helping to clean up.

“Move it, Vasya,” she says. “They've changed their minds before.”

I look into the room, and Stukachov is there,

too. He smiles at me briefly. He's piling our broken things on top of my dad's bedsheet, which is still stained with his sweat. Then he lifts the edges and ties the corners together. He takes the sack out and sets it in the corridor next to our other things, all broken. Then, as though I'm not there, they start moving their things into our room. Stukachov's mother comes in fast, carrying her pillow. It doesn't take them long to set up their furniture, make the beds, and bring their sleeping kids one by one and tuck them in.

too. He smiles at me briefly. He's piling our broken things on top of my dad's bedsheet, which is still stained with his sweat. Then he lifts the edges and ties the corners together. He takes the sack out and sets it in the corridor next to our other things, all broken. Then, as though I'm not there, they start moving their things into our room. Stukachov's mother comes in fast, carrying her pillow. It doesn't take them long to set up their furniture, make the beds, and bring their sleeping kids one by one and tuck them in.

It all happens so quickly, I don't even know yet how I feel about sharing our room with them. I start to walk in, but Stukachov blocks the door. I reach for the door handle, but his hand is clutching it. He leans in close. “Your daddy's been arrested,” he says. “There's no room for you here.”

I step back. He nods approvingly, steps into the

room, and closes the door. “He'll enjoy the orphanage,” he says to his wife. “All nice children.”

room, and closes the door. “He'll enjoy the orphanage,” he says to his wife. “All nice children.”

The lock clicks.

I'VE NEVER BEEN out alone in the middle of the night. A wind rattles the courtyard's gate as I peer into the dark street. Not a citizen in sight. I know there's nothing to be afraid of, and yet I don't go out there; I step back into the courtyard and look up at our dark window. The Stukachovs are sleeping, warm and cozy in our room. Tomorrow they'll throw away our broken things. That doesn't matter, of course. My dad and I oppose personal property on principle. Personal property will disappear when Communism comes. But still.

I need to think things over. I could go back and sleep on the floor in the kitchen, next to the stove; I bet it's still warm after all the day's cooking. It's a large iron stove with twelve ringsâone ring per family. After my mom died, we put a little Primus stove into our room for warming things up and gave our ring on the stove to the Stukachovs; with so many dependants to feed, they needed it more. Maybe that's what my dad meant when he said, “Don't talk to Stukachov. He'll use it.” First we gave him the stove ring; now he's taken our room.

Maybe I don't need a room. Not everybody has one. Marfa Ivanovna doesn't have a room. She lives in a cubbyhole next to the toilet. Semenov sleeps behind the curtain in the corridor, and nobody's complaining. I feel better already. I'm staying in the kitchen until my dad returns.

Walking back to the door, I step over some tracks frozen into the snow. When I see these are the tire

tracks from the car that took away my dad, I stop. Going back in that apartment is a weakness, not fit for a future Pioneer. They clearly arrested my dad by mistake. Wait till Stalin finds out.

tracks from the car that took away my dad, I stop. Going back in that apartment is a weakness, not fit for a future Pioneer. They clearly arrested my dad by mistake. Wait till Stalin finds out.

But how long will it take before they tell Stalin? Stalin is busy; he has to take care of all of us, millions all over the country. And what if they don't tell him for a long time? Could be several days even. Who knows? My dad has to be at our Pioneers rally tomorrow by noon. There's no time to waste. I will tell Stalin myself.

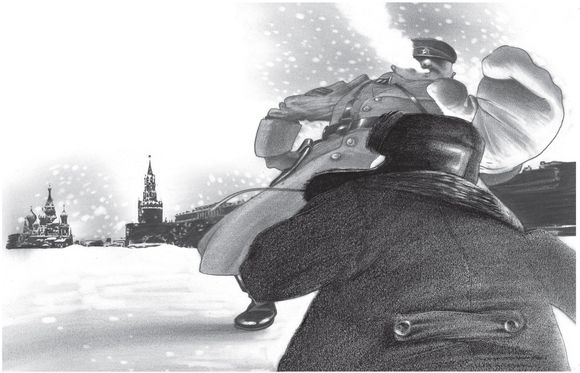

RED SQUARE is deserted, layers of cobblestones under thick black ice. To go faster, I slide, my boots skimming over reflections of ruby stars that glow atop the Kremlin towers. The Kremlin is where Comrade Stalin's office is. Everybody knows his windowâit's lit all night long. Our Leader works hard.

I imagine I'm there already, in Stalin's office. He is sitting behind his desk, smoking his pipe. “No time to lose, Comrade Stalin,” I say. “My dad has been arrested!” He raises his eyebrows. He grabs

the telephone. “Special unit! Emergency!” he says. “Wrench Zaichik's dad from the traitors' claws!”

the telephone. “Special unit! Emergency!” he says. “Wrench Zaichik's dad from the traitors' claws!”

But when the Kremlin guards see me, they run across the square, shouting and tugging at their sidearms. One slides on the ice and bumps into me. He swears, steam bursts out of his mouth, and he plunges his enormous mitten into my face. I duck under and run. The guard blows a whistle and other whistles join in. Suddenly, guards are everywhere. One slips and falls, and his pistol goes off like a whip crack. At the far end of the square, a black automobile turns the corner, headlights slashing me in half.

Other books

Amanda Scott by Ladys Choice

War of Power (The Trouble with Magic Book 3) by B. J. Beach

The Ghost of Cutler Creek by Cynthia DeFelice

Taking Jana (Paradise South #2) by Rissa Brahm

Don't Cry Over Killed Milk by Kaminski, Stephen

Never Tied Down (The Never Duet #2) by Anie Michaels

Beware the Black Battlenaut by Robert T. Jeschonek

Buried for Pleasure by Edmund Crispin

Goodnight, Beautiful: A Novel by Dorothy Koomson

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum