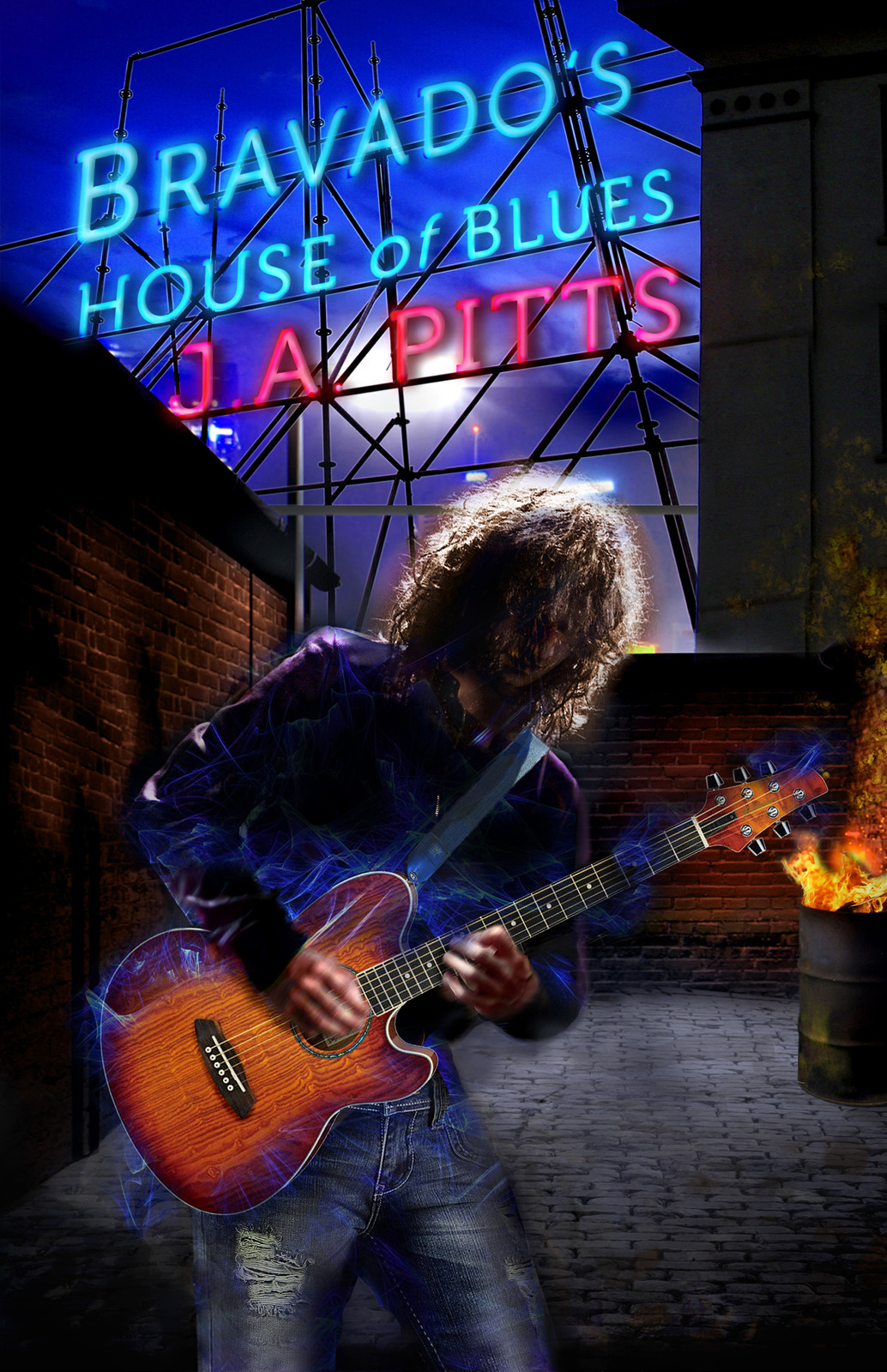

Bravado's House of Blues

Read Bravado's House of Blues Online

Authors: John A. Pitts

- The HEART and BONES of STORY and LIFE

- THREE CHORDS and the TRUTH

- THERE ONCE WAS a GIRL from NANTUCKET (A Fortean Love Story)

- TOWFISH BLUES

- HOW JACK GOT HIS SELF a WIFE

- The HARP

- LUCK MUSCLE

- The HANGING of the GREENS

- F*CKING NAPALM BASTARDS

- MUSHROOM CLOUDS and FAIRY RINGS

- DEAD POETS

- BLACK BLADE BLUES

- CROW and TURTLE

- HOWLING

- BONES of my FATHER

- STORY NOTES

- ABOUT the AUTHOR

J. A. PITTS

FAIRWOOD PRESS

Bonney Lake, WA

Also by John Pitts

Black Blade Blues

Honeyed Words

Forged in Fire

Bravado’s House of Blues

A Fairwood Press Book

November 2013

Copyright © 2013 by John A. Pitts

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Fairwood Press

21528 104th Street Court East

Bonney Lake, WA 98391

www.fairwoodpress.com

Cover illustration by Paul Swenson

Cover Design by Paul Swenson

Book Design by Patrick Swenson

ISBN13: 978-1-933846-41-5

First Fairwood Press Edition: November 2013

Printed in the United States of America

eISBN: 978-1-62579-255-6

Electronic Edition by Baen Books

COPYRIGHTS

“Three Chords and the Truth” first appeared in

Talebones

(Winter 2009)

“There Once Was a Girl From Nantucket” first appeared in

Fortean Bureau

(April 2006)

“Towfish Blues” first appeared in

Talebones

(Winter 2008)

“How Jack Got His Self a Wife” first appeared in

The Trouble With Heroes

(Tekno Books, 2009)

“The Harp” first appeared in

10Flash

(October 2011)

“Luck Muscle” appears here for the first time

“The Hanging of the Greens” first appeared in

Aeon

(August 2011)

“F*cking Napalm Bastards” first appeared in

From the Trenches

(Carnifex, 2007)

“Mushroom Clouds and Fairy Rings” first appeared in

Courts of the Fey

(Tekno Books, 2011)

“Dead Poets” first appeared in

Zombie Raccoons & Killer Bunnies

(Tekno Books, 2009)

“Black Blade Blues” first appeared in

Swordplay

(Tekno Books, 2009)

“Crow and Turtle” appears here for the first time

“Howling” appears here for the first time

“Bones of My Father” appears here for the first time

To Kenny for sharing the walk

To Jay for leaving bread crumbs

and Kathy who winced every time I got an SASE in the mail over the last 25 years, but loves me anyway and believes in my dreams.

The HEART and BONES

of STORY and LIFE

by Ken Scholes

I

n 1997, just a few years after my slow return to writing, I discovered the existence of critique groups. I’d started sending stories out, collecting the fair share of rejection slips that all beginning writers are obligated to collect, and I decided to see what other support was out there.

I had no idea what I was going to find.

I learned about a crit group in Seattle open to whoever wanted to participate, so I decided to give it a try. I distributed my story to its members and waited for Saturday’s session to come around. Now, this group was a large, diverse cast of writers, most unpublished. The styles and genres present were wide and vast, as was the quality of feedback. And one writer in particular took great issue with my use of religion in a science fiction story. “Religion,” he said, “has no place in science fiction.” There were lots of wonderful things said by others, but all I heard was this single writer’s opinion.

It must’ve showed on my face. Because as I was leaving (never, of course, to return), another writer stopped me in the yard. He was earnest, he was enthusiastic, and he wanted to make sure that I knew my story’s religious aspects were certainly a welcome and important part of the genre. I think it was the first time I heard John “J.A.” Pitts tell me, “Well, their vote doesn’t count.” He’s said it to me so many times over the years that it’s now part of my own vocabulary. We were instant friends, and it’s one of those bedrock friendships you count on like the rising of the sun.

Truth be told, he was my first writing friend.

So imagine my delight to be here, introducing you to him and his work.

John and I were instant friends, and right away he became my very first “beta reader.” For the most part, with the exception of our more recent writing, we’ve had our eyes on one another’s words since that October Saturday when we first met. We’ve broken in together, slowly and painfully, over a long course of years. And that brings us to today.

Right now, you’re holding a book that I watched born over the course of sixteen years, story by story landing in my inbox fresh from the hot skillet of John’s imagination. It shows what happens when an astute observer of human interaction with an ear for beautiful language and an intrinsic sense of how to use the full range of sensory data uses imagination to tap into life and show us what is important, beautiful, true and tragic.

I dare you to read the embalming scene in “Luck Muscle” and not twitch a bit at the visceral but matter-of-fact deliver of detail. Or to not fall under the poetic spell of his Southern voice in “How Jack Got His Self a Wife.” And across the landscape of stories like “Three Chords and the Truth” and “The Hanging of the Greens” we see a gentle morality play—choices and consequences—juxtaposed against the romantic, playful nature of stories like “The Harp” and our collaboration, “There Once Was a Girl from Nantucket: A Fortean Love Story.”

These days, John has been spending his writing time mostly as “J.A.” Pitts, chronicling the life and adventures of one Sarah Beauhall—a modern day blacksmith wrestling with her sexual identity and her unexpected part in Norse mythology. His series has won awards for his portrayal of this complex, layered character, and that recognition shows the one thing I’ve always known about John: He loves his characters like he loves the people in his life, and embraces, without judgment, the whole picture of who they are and seeks to understand them. Fans of that series will be delighted to see three stories from that universe here, including “Black Blade Blues,” the story that started it all. I was in the room when Dean Wesley Smith told John that it looked like an excellent beginning to a novel. I chuckled when he said it because it was something John had been hearing from me and others about a lot of his short stories. He’s proved us right with his transition into novels. But the heart and bones of story and life lived here in his short fiction long before the novels came out, and I’m honored to have watched each born over the years and to now introduce them to you.

So settle in and get ready to meet a cast of characters so diverse that you’ll see people there you’re sure you know . . . or maybe even see yourself. Get ready to feel and think things you never quite felt or thought before. And get ready for a voice that plays to a wide audience in its fluid strength and stories that sing the human spirit in all its beauty, fear and sadness.

It’s showtime at

Bravado’s House of Blues

and you, my lucky friend, have a first row seat.

Ken Scholes

Saint Helens, OR

September 2013

THREE CHORDS

and the TRUTH

E

than careened around the fountain where the water fell in sixteenth notes. His boots thudded along the cobblestone square as he picked up speed, his backpack bouncing on his left shoulder. Crowds of college students flowed between the buildings of the University of Washington campus, forming a slalom course for his flight. Their voices arced outward in shimmering bursts of song, violets and pale blues streaming through the bright clear morning.

Class had not yet ended, when the itching at the tips of his fingers had begun to grow, throbbing with the punctuated musical tones that reverberated through him. When the increasing cacophony drowned the professor’s voice, he fled the classroom. The calling slammed into him like a hurricane, overwhelming with incomprehensible strength.

The sounds of the city distorted, confusing his senses. Spikes of pain flashed down his arms by the time he crossed University Avenue and rushed into his apartment.

The pull of the guitar roared in his head, jangling his raw nerves. He scrubbed his fingertips along his chest to take the edge off the itching and bolted up the stairs, two pounding half notes at a time.

He fumbled the keys, wincing as they scraped against the lock with a discordant G minor chord. Finally, he pushed the door open, and he dropped his pack in the chrome and vinyl chair beside the kitchen table.

The apartment smelled of stale beer and old socks. He stepped over a sleeping form in the living room, blanket pulled up over her head. Pink panties winked out from the edge of the covering. He paused a moment, a pang of loneliness driving against the pull of the guitar.

Another fully-clad body lay draped over the couch, one leg off onto the floor, one arm flung over a shaggy head of hair. Refugees from another night of college life.

The minefield of sleeping bodies stood between him and his guitar. Wincing as the itching turned to burning, shooting pain up his forearms, he stepped over and around the bodies that covered his floor.

The door to his roommate’s room stood open. Harmonic snoring told him that Ian had finally hooked up with that biology student he’d been earnestly chatting up last night. Ethan smiled briefly. The emptiness crescendoed into his belly. With a sigh, he pulled the door closed and stumbled to the end of the hall.

His small room was just as he’d left it hours earlier, stark and empty of life. A single desk sat against one wall, piled with papers. Posters of his favorite musicians and groups covered the walls: Pink Floyd’s

Dark Side of the Moon

, Led Zeppelin, Joe Satriani. He tossed his jacket over the back of his straight-backed chair, grabbed his guitar case from under the bed, and climbed out his window.

He had the smallest room in the house, but it had access to the

beach

. He walked along the ledge to the roof of the large front porch—a ten-by-twelve swath of tar and heaven. He shoved several dead soldiers off the spool-table with his guitar case, the glass bottles thudding against the thick tar surface. He flopped into the ancient lime-green armchair, flipped the latches on the case, and raised the lid.

The old guitar called to him like a lover, the deep red wood glowing in the new morning sun, the memory of it filling his mind. He gingerly pulled the instrument out of its crushed velvet lining, and the need intensified. Not since his grandfather’s death had the guitar called to him so urgently.

Gritting his teeth against the maddening sensation, he fell back into the chair, threw his left leg over the arm, hugged the guitar to his stomach, and placed his hands on the strings.

The first note sprang into the chill morning, followed by a second, and a third. Ethan took a deep breath and launched into the song that sang in his head. A warmth spread outward from his fingertips, soothing the itching as the sweet melody of a new piece burst forth, stilling the chaos of the world.

The next morning, Ethan sat on a milk crate in front of the new art gallery/coffee house on the corner of Stewart and Pike Place and tuned his guitar. His case stood open at his feet, three worn singles in the bottom as seed. After a few minor adjustments, he dashed off a quick chord change, cleared his throat, and eased into the song that had haunted him since the day before. He hummed, unsure of the words, but his fingers danced along the frets, sure and strong, each note a delicate bit of joy and sadness.

He watched the crowd move through the Market, freaks and yuppies mingling in the smells of fish, strong coffee, and fresh bread. His music mingled with the song of the Market—the hum of the crowd, the calls of the gulls, and the cries of the fishmongers.

Ethan scanned the crowd for the hippie girl who had a booth on weekends, but she wasn’t around. He’d hoped to get up the nerve to talk to her this week.

Instead, he spied a small Hispanic man across the road washing out a large white bucket, his back bent to reach the spigot. When the man finished, he placed one hand on his back to help straighten his spine. He lifted the now clean and full bucket of water and walked back toward his stall of garlic, peppers, and fat juicy grapes. The man paused, glanced Ethan’s way, and acknowledged him with a slight nod. The look on the man’s weathered face spoke to Ethan of toil and strife.

Ethan returned the smile, and the words to the new song flowed from his lips.

The morning sun is our mother, waking us to our day.

She succors us and gives us life.

But the moon is our lover, coming to us in the night.

We dance in her glory and sleep in her gaze.

Ethan sang on, the words flowing through him, filling the market with his rough tenor and the delicate notes from his guitar. He sang with passion and blind faith, knowing he would remember the song later, word for word. He reveled in the joy; his chest swelled with it. He turned his head to the side, eyes closed, and sang the last few lines. This is what his grandmother always meant when she talked of the spirit moving in you. Only Ethan knew he wasn’t a vessel to hold the spirit, but a conduit for its transmission.

As the last note faded, and the guitar’s vibration seeped into him, Ethan opened his eyes. A small crowd of passers-by had stopped in front of him, staring. The market held its collective breath for one quick second, then the applause washed over him. He smiled, and the crowd began to dissipate. The case held several handfuls of change and a few more bills. He didn’t look too closely, not wanting to jinx it. Three Navy guys in their dress whites walked up and dropped a couple of bills into the case.

“Not sure what you were singing about,” one of them said, “but it was damn fine.”

“Thanks,” Ethan said as they walked away.

The elderly Hispanic man from across the way stood in the back of the dissipating crowd, tears running down his weathered cheeks, a broken-toothed smile filling his face. The weariness had fallen away, leaving a mosaic of joy.

“Gracias,” the man said, stepping forward and placing a bag of fat, red grapes into Ethan’s case.

Ethan answered without thinking. “De nada.”

*

He spent the rest of the morning covering well-known folk songs and popular ballads. Several times during his two-hour slot he paused when the crowd thinned and watched the people. He loved to imagine who they were, what their lives were like. He could play some songs without effort, the simple lyrics flowing from him, unhindered by the thought process. It allowed him time to absorb this world.

Susan, the young cellist who followed Ethan on Saturdays, dropped a dollar into his open case as he finished his last song. He winked at her as the last words swam among the shoppers. The a-cappella group from down by Starbucks finished their set to wild applause. Ethan gathered his bills and the grapes, then tipped his guitar case, pouring the loose change into the bottom of his pack. Then he gently placed the red guitar into its formed cushion and closed the latches. He stood, stretching his hands above his head as Susan began to run through her scales. He admired her bow work, and the way her fingers flew along the neck of the cello. She slipped into “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” with her eyes closed, a hint of a smile touching her lips.

“You’ve got real magic there,” he said when she stopped.

“Thanks.” Her smile spread across her face like the sun rising.

He slung his pack over his left shoulder, picked up his guitar, and started walking toward the French bakery. “Have a good set,” he said.

She nodded, and her bow began to dance.

He paused outside the bakery, nibbling his chocolate meringue and watched Susan perform. She was mousy and petite, but she glowed with the passion of her music. He especially liked the way her face looked when she played—eyes closed and rapt with pleasure.

Ethan browsed his way along Pike Place and tipped each busker—sowing the wealth and harvesting the good karma.

He asked several of the regulars if they’d seen the young hippie girl who usually set up shop just north of the last covered stalls. She sold intricate twists and braids of crystal and silver. Ethan thought about getting his ear pierced, just so he could buy something from her.

No one had seen her.

He walked to the edge of Victor Steinbrueck Park, sat on the grass with his guitar to his left and his pack in his lap. He dug out his journal and wrote down the lyrics from that morning. Only after he finished did he notice the lyrics were in Spanish. Now that was a first. His grandfather had been a migrant worker, but Ethan knew very little Spanish. He didn’t question the muse and her work, just accepted her gifts for what they were. He took out his guitar and played the song again, softly, joyfully.

One of the other buskers, a middle-aged woman, with short-spiked hair and bangles covering her blouse and peasant skirt, walked up to him as he finished. “Mighty fine sound you’ve got there.”

“Thanks,” Ethan said.

She held out her hand. “Name’s Ellie Richardson, but my friends call me Skook.”

Ethan took her hand (firm grip) and smiled broadly. “Nice to meet you Skook. I’m Ethan.”

She appraised him for a minute, making up her mind about something. “Nice guitar you got there. Where’d you get it?”

Ethan held it up by the neck. The sun gleamed off the polished wood. “Used to be my grandfather’s.”

“Damn nice instrument,” she replied. “You ever wanna get rid of it, you look me up. I’m usually playing over by The Clock.”

Ethan chuckled. “I appreciate the offer, but I think I’ll hang onto it.”

Skook picked up her battered guitar case, slung it over her shoulder, and walked away waving. “Don’t you forget.”

He made a final pass down Pike Place before giving up on meeting the hippie girl this weekend. It was odd that her booth sat empty, forlorn. Even the tall Rasta-Punk who sold T-shirts at the next stall seemed worried when Ethan asked.

“Kari loves coming out here,” he said. “Not like her to give up this spot. Took her three years to work her way up the list.”

“Kari, huh?” Ethan said with a smile. “You know her well?”

“Not real well. She’s a cool chick,” Rasta said, scratching the side of his face. “Been having some trouble with her old man though.”

“Her father?” Ethan asked.

Rasta laughed. “No dude, her dickhead boyfriend.” His hair seemed to vibrate when he laughed. “Man, she split from home when she was just a kid. Some loser scene back in Kansas somewhere.” He paused to take the money from a couple in shorts and Hawaiian shirts. After they’d stuffed their new T-shirts into their backpack, he turned back to Ethan. “Nah, I’m talking about that college dude she’s been dating. Real pretty boy.” Rasta leaned in close enough for Ethan to smell the stale coffee and staler cigarettes. “Control freak, if you ask me.”

Ethan lowered his voice. “Rough guy?”

Rasta shrugged. “Big guy, got money.”

“Oh.”

“Hey, I heard you earlier. You got a good sound. You should do more original stuff.”

Ethan smiled. “Thanks. I did a new piece this morning.”

“Yeah,” A look of profound respect crossed Rasta’s face. “I talked to Alejandro earlier. That dude is about four days older than dirt. Worked his whole life picking crops. He told me your song made him cry like a baby.”

“The guy selling the garlic and peppers across from Stewart Street?”

Rasta nodded.

“Alejandro gave me a bag of grapes as a tip.”

Rasta raised his bushy eyebrows. “Awesome, bro. Alejandro has his first nickel. Dude can barely keep a roof over his head. You should be flattered.”

“Thanks,” Ethan said, thoughtfully.

“You just keep making music.”

Ethan nodded. The crowd swirled their way again. Lots of folks with money to burn.

“Listen,” Rasta said, moving back behind his booth. “I’ll tell Kari you’re looking for her.”

Ethan blushed. “Well, she doesn’t know me, really.”

Rasta laughed again. “You smitten, little dude?”

Ethan grinned and waved. “Thanks for the information.”

“Peace.” Rasta flashed him a two-fingered salute and returned to hustling the crowd.

Ethan strolled south, weaving in and out of the throng as he worked his way back to Pike Street, where he’d turn east and head toward the bus tunnel. He needed to get back to the university and do some research in the library. He’d come back tomorrow, he decided, and look for Kari again.

Rasta apparently didn’t work the T-shirt booth on Sundays. A small Asian woman sat behind the card table, compulsively straightening the shirts. Kari’s spot was empty again. Disappointed, Ethan walked down to Three Sisters Bakery and got a cup of coffee and a croissant. He stood and listened to one of the old-timers working his piano and singing ballads. He tipped the guy and headed back to his apartment.

The next weekend arrived gray and spitting rain. The crowds were sparse and the tips worse. The smell of the sea rolled over the market in warm bursts, overpowering the smells of bread and fresh cut flowers. Ethan watched the few who braved the weather as he huddled back against the side of the building and played. They seemed subdued, almost melancholy. They walked the booths, but Ethan sensed they got no joy from it. He was nearing the end of his set when a long, low C chord rumbled up out of the earth, and the itching overcame him.