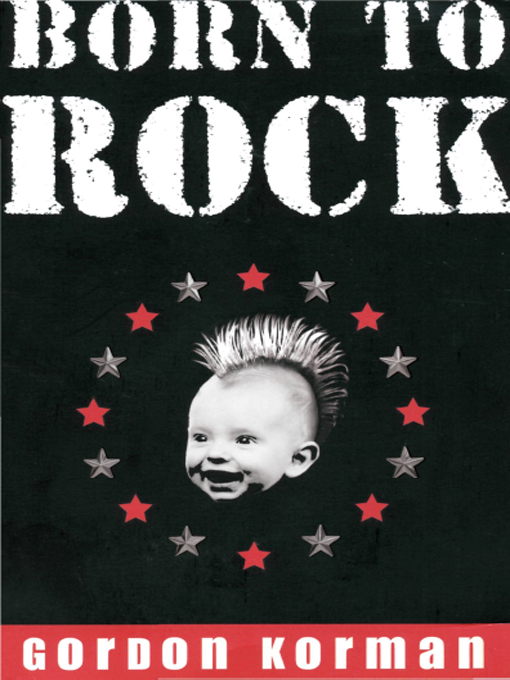

Born to Rock

Text © 2006 by Gordon Korman

All rights reserved. Published by Hyperion, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Hyperion, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690.

ISBN 978-1-4231-4128-0

Cover design by Ellice M. Lee

Photos adapted from © Meeke/zefa/Corbis and © 2006 by Lisa Whiteman

ALSO BY GORDON KORMAN

The Juvie Three

Schooled

Son of the Mob: Hollywood Hustle

Jake, Reinvented

Son of the Mob

The 6th Grade Nickname Game

No More Dead Dogs

For

LEO FRANCIS KORMAN

,

BORN TO ROCK 4/17/05

Contents

PROLOGUE

The thing about a cavity search is this: it has nothing to do with the dentist. If only it did.

They can give it polite names, like “additional inspection” or “supplemental investigation.” But the fact is, you're bent over, grabbing your ankles, while some total stranger has his fingers in a very private place where nobody should be rummaging around.

Don't get me wrong. It doesn't scar you for life. You don't suffer from post-traumatic stress syndrome. But no one who has been through it is ever quite the same again. The experience is justâ

big.

I'll go even further than that. There are two kinds of people in this worldâthose who have had a cavity search, and those who haven't. This is the story of how I wound up in the wrong category.

It's the story of other things, too. A cavity search, while excruciatingly memorable, doesn't actually define who you turn out to be. When I was president of my high school's Young Republicans, accepted to Harvard, and on a fast track to a six-figure income, I believed that we are masters of our own fate. Now I know that just the opposite is probably true. You are the sum of what happens to you, a pinball, bouncing from bumper to bumper, hoping the impact of the flippers won't hurt much. That theoryâhow I came up with it, anywayâturned out to be all part of my inexorable journey to that little room the Cleveland PD called Exam 3.â¦

[1]

THE TERMS

YOUNG REPUBLICAN

AND

cavity search

don't often appear together. Republicans don't have cavity searches. According to my oldest friend, Melinda Rapaport, we don't even have cavities.

But I wasn't born Republican. It's not genetic. Believe meâI'm familiar with genetics. I have McMurphy, the eight-hundred-pound gorilla I carry in my DNA, a total loose cannon rolling around my personality.

We all have wild impulses from who-knows-where. In my case, I know exactly where. Mine come from McMurphy.

The only connection between genetics and being a Republican is that I joined the G.O.P. to help myself control McMurphy. And even that's not technically true.

The real reason was Congressman DeLuca. It was two summers ago. Gates signed on to help out with DeLuca's re-election campaignâthat's Caleb Drew. We called him Gates because he was the next Bill Gates for sure. He brought Fleming Norwood. I only went by campaign headquarters to keep those guys company. The minute I saw Shelby Rostov stuffing envelopes, I was lost. Blond, blue eyes. Not just hotâShelby was what you always pictured when you envisioned the ideal of hot. The effect was so striking that I almost

recognized

her:

Hey, don't I know you from my wildest dreams?

I grabbed a pile of envelopes and started stuffing right along with her.

“Fresh blood?” she asked. Her smile was so beamingly bright that I had to keep from squinting.

“The freshest.” Boredom had brought me to the G.O.P. Love kept me there.

Congressman DeLuca was the kind of guy who was easy to support. He just seemed so different from other politicians. For starters, he was pretty youngâlate thirtiesâwith loads of charisma. When he talked about something, you really wanted to believe him. His ideas weren't super-conservative; they were common sense. That was his campaign sloganâThe Common Sense Revolution.

The only flak I caught over working for the congressman came from Melinda. To say that she was un-Republican was to understate the matter by one thousand percent. On the outside, she was somewhere between goth and punk, but her gut was pure, unadulterated liberal. Her heart bled for every twig and spotted owl. If there were a People for the Ethical Treatment of Amoebas, she would have joined. To her, there was nothing more despicable in this world than corporate profitsâunless the money could be diverted to buy Wite-Out to erase Christopher Columbus from all the history books.

“You joined the

Republicans

? Leo, what's wrong with you?”

“You should meet Congressman DeLuca,” I argued. “He's the real deal.”

“He's the devil.”

“Come on!” I snorted.

“Oh, sorryâthe devil is the guy with the pointy tail, plotting for everybody's soul. Like a supernatural being has nothing better to do than obsess over whether or not I pierce my tongue. P.S.âmind control.”

“Nobody controls my mind,” I defended myself.

“In all the time I've known you,” she said dramatically, “I never thought you'd get suckered in by the Big Lie.”

There was no arguing with Melinda when she started a sentence with “In all the time I've known you.” Besides my parents, she knew me longer than anyone. We were toddlers together, beating each other over the head with toys while our moms had coffee. As far back as I could go, there had always been a Melinda. She knew everything about meâexcept McMurphy. I didn't tell anybody about him.

This was Melinda's official response to me working for the G.O.P. She volunteered for DeLuca's opponent. The Democrat? Not on your life. She signed on to stump for a candidate named Vinod Murti. I don't remember the party affiliation, but their only two issues were legalizing marijuana and yogic flying. (Don't ask.)

Vinod ran out of money before Election Day and left the state, sticking his supporters with an eleven-hundred-dollar tab from the local vegan restaurant. Our guy won by a landslide.

I was hooked. Success is a heady business.

Here's an example of the sheer nerve of Melinda. She actually expected me to bring her along on the victory party cruise that Congressman DeLuca threw for his campaign staff.

“Absolutely not!” I told her. “You worked for his opponent. Go on

his

cruiseâmaybe he's got a rowboat.”

Yet even as I was arguing, I knew exactly how it was going to turn out. She was going, and I was taking her. Period. There were no threats, no bribes. She simply refused to accept that it wasn't going to happen. And it happened.

She was already pretty punked out by then, so she stood out like a sore thumb.

The cruise was a nightmare. Gates couldn't take his eyes off her, as if a rare exotic monkey had somehow found its way onto our boat trip. She bad-mouthed the congressman from bow to stern and back again. She got into a beef with Fleming about her spiderweb tattoo, and wound up giving him the finger in front of half the Connecticut G.O.P.

“Is that your girlfriend, Leo?” Shelby asked in awe.

I tried to laugh it off. “God forbid!”

“But you guys came together, right?”

What could I do? Deny it?

“Old friends,” I mumbled. “Like from the Cretaceous period.”

Later that night I saw Shelby making out with Fleming on the poop deck. If I'd known that getting flipped off by a goth-punk was such an endorsement in her eyes, I'd have made a deal with Melinda to punch me.

As parties went, it wasn't my favorite. Still, that was the night Representative DeLuca offered to be our sponsor for a chapter of the Young Republicans at East Brickfield Township High School. At that moment, in the glow of his election victory, we would have followed the guy over the rail into the chilly waters of the Long Island Sound. We were sold.

Funny thingâthroughout the whole ride, I moved heaven and earth to steer Melinda away from the congressman. It made sense, right? The distinguished gentleman from Connecticut shouldn't have to be abused on his own boat trip. But when their paths inevitably did cross that night, Melinda was totally polite and respectful. She even shook his hand and congratulated him on his victory.

It was the weirdest thing of all about Melinda. Just when you thought you had her figured out, she'd do the exact opposite of what you expected. Gates was bug-eyed. I think she scared him.

As for Shelby, I don't think I really was in love with her. That was probably just McMurphy.

Why did I let Melinda push me around? Sure, she was stubborn and determined, but she wasn't the Mafia. All I had to do was say no and stick to it. I never did.

For some reason I was incapable of standing up to the girl. I definitely wasn't attracted to her. She wasn't exactly my type, with the black clothes, black hair, black lipstick, black nail polish, and black tattoo. The only thing that wasn't black was the nose ring (gold). Not only did she adore punk bands with names like Purge and Sphincter 8, but she had to look like them too.

Don't get me wrong. On the weirdness scale at our high school, she was no more than a seven. But Melinda wasn't the girl next door, unless you lived at 1311 Mockingbird Lane, and your neighbors were the Munsters.

It's not that I didn't try to assert myself. I knew her every bit as well as she knew me. The punkier and more gothic she got, the less she fooled me. Punks are raw-meat people, not macrobiotic vegetarians.

But every time I was about to tell her off, I would remember that day back in fifth grade. Our fathers used to take the same train into the city every morning. It was Dad's turn to get the coffee. And by the time he returned with the two hot cups, Mr. Rapaport had collapsed on the platform. Heart attack. He never woke up.

My father quit his Wall Street job at the end of the same week. He bought a small hardware store in town.

So every time I was ready to unload on Melinda, I would back off and let her have her way. Guilt, probably, for having a father when she didn't.

[2]

HIGH SCHOOL REPUBLICANS: I KNOW

what that sounds likeâa bunch of preppy dorks who are too short for basketball and too skinny for football, so they track mock stock portfolios and talk about what model of Range Rover they're going to buy someday. But honestly, we weren't that bad. We didn't look down on everybody else. We were just doing our thing. And it didn't hurt that in the process, I was sticking it to McMurphy. I didn't know much about my genetic hitchhiker, but I was reasonably sure he wasn't a Republican.

So I hung out with Gates, and Fleming and Shelby, who were hot and heavy by then. Luckily, I was over her, but I suspected McMurphy was still carrying a torch, because nothing gave me more satisfaction than getting the better of Fleming. When my virtual stock portfolio beat his at the end of junior year, I was so overjoyed that you would have thought the fifty-six million dollars in it were real.

Melinda never gave up on trying to liberalize me.

“It's just a school club,” I defended myself. “I haven't turned into a heroin addict.”

She would have preferred me hooked on drugs. “Sixteen, and all you care about is how much money you'll be making a decade from now. P.S.âshould I barf now or later in the privacy of my own home?”

“What's wrong with money?” I demanded. “We're going to have to get jobs at some point. Why not get a good one? If I have to work all day, at least I'll have something to show for it.”

“Oh, almighty dollar, we pledge obeisance to thee!” Melinda had been in drama until the Big Dustup. (There are no goths in

Bye Bye Birdie

, and Melinda wouldn't wear Capri pants if you threatened her with an ax.) “What about fun? What about love?”

“Rich people fall in love.” The fact that I was defending my life choices to someone who had once tried to wear the thin bone of a chicken wing through her nose was an irony that didn't escape me.

She didn't even hear. “What about ideasâstaying up until four in the morning dissecting a great book or a great film? What about art?”

“It's a fantastic investment,” I told her. “Do you know what a Renoir goes for these days?”

I don't know why I worried so much about her sensibilities. She was the toughest person I knew. While we were in the middle of this conversation, some jock from the basketball team was trying to pass behind Melinda with his lunch tray. She had a way of straddling the cafeteria bench that placed her bulky black-and-chrome biker boots in everybody's way.

As the guy squeezed by, he muttered, “Freak,” under his breath. I'm surprised she heard it. I barely did.

Without missing a word of her righteous lecture about books, films, and art, she snapped up a black-clad elbow into the bottom of the guy's tray.

It was a marvel of physics. Not one drop of Salisbury steak and mashed potatoes missed him.

The jock wheeled on her. “Heyâ!”

She froze him with a look. It wasn't a threat; it wasn't even a challenge. It announced, as clearly as if it had been spoken aloud:

Your opinion equals one tiny turtle turd.

Aloud, she said, “Whoopsâinvoluntary muscle spasm.”

He decided that wearing his lunch from chest to crotch was a fair exchange for avoiding the unpleasant scene that was surely brewing. He quickly spotted some basketball buddies and hurried over.

Melinda turned back to me. “What about music?”

I knew that was coming. Melinda wasn't just a music fan. She lived and breathed music. At least she called it music. I wasn't exactly cutting edge, but I like to think I had some taste. The stuff Melinda picked to worship was the God-awfulest noise to come out of anyone's nightmare since the old A-bomb tests at Yucca Flats. Even the genre names sounded more like a gangster's rap sheetâpunk, thrash, headbanger, metal, hardcore.

The fact that I didn't like it went without saying. But I couldn't even figure out what made it music.

“Look,” I ventured. “You care about what you care about. Let me care about this. How many times have you lectured me about accepting people's differences? This is my difference. Accept it.”

“I'd accept itâif it were the real you.”

How can you argue with someone who knows everything?

Luckily, I had another friend who really

did

know everything. Good old Gates. It would be exaggerating to say that he'd memorized the Internetâbut not by much. It was Gates who figured out that Melinda was actually KafkaDreams, a regular contributor on Graffiti-Wall.usa, the online billboard. Graffiti-Wall's motto was “Upload, Download, Unload,” which sounded like Melinda's style, the unloading part, anyway. Stillâ

“How do you know it's her?”

He handed me his PDA, an old Casio he'd rewired to receive radio signals from Andromeda. “Take a look.”

KafkaDreams Wall of Shame,

Worst of the Worst

Top (bottom) 5:

#1âWar. Nuff said. P.S.âCamouflage sucks.

#2âJocks. Just cause you can put a ball through a hoop doesn't mean you own the world. Wake up and smell the Desenex.

#3âHomophobia. I'm forming a hate group prejudiced against intolerant people.

#4âYoung Republicans. What a bunch of bozos. P.S.âHaven't seen this much constipation since the great Ex-Lax embargo.

#5âTwo wordsâTater Tots. Two moreâObesity Epidemic. COUSCOUS RULES!!!

I turned to Gates. “How'd you find this?”

“I scanned the traffic that was routed through the school's server,” he explained.

“All of it?”

“I did a search for âcouscous.' She talked about it on the boat tripâabout how the buffet was a coronary waiting to happen.”

He was rightâGates was always right. This was Melinda to a T. But why would a computer superstar with a billion things on his mind waste his time on it? Unlessâ

“You've got a crush on Melinda?”

He didn't deny it. “What's wrong with her?”

“She looks like a vampire,” put in Fleming from the depths of

The Wall Street Journal.

“Go back to your stocks,” I told him. I could put Melinda down, but coming from Fleming, it got on my nerves.

Gates shrugged. “I think she'd clean up nice.” Fleming peered out from behind his newspaper. “Dude, you're going to rule the world someday. The president of Microsoft can't be married to a mutant.”

I faced Gates. “You're seriousâMelinda.”

“Yeah.” A goofy grin split his face. “She'sâfeisty.”

“Melinda

Rapaport

?” I wasn't giving him a hard time. I was struggling to see what he saw. I'd known her my whole life, but I'd never once conceptualized her as a

girl.

Especially not under all those layers of gothica. She was the last person you'd ever match with Gates, who was not just brilliant, but more than a little on the nerdy side. A guy like that should run a mile at the sight of her. Even her Web postings seemed more suited to an anarchist than a high school girl:

12-18

We go to school every day. Why? Because it's the law? If nobody showed up, what could they do? Put us ALL in jail? We're such sheep!

P.S.âBaaah!

1-17

The problem with wimps is that they're too wimpy to know what wimps they are.

2-10

Life's too short to be nice to people you hate. While you're nodding and smiling at some jerk, the clock is ticking. Pretty soon you'll be dead, under a hunk of marble that says, “Here lies an idiot who wasted his life being polite to people who didn't deserve it.”

Feisty? Crazy would be more like it. Gates ought to have his head examined!

My eyes fell on the latest entry:

3-22

Seven years since Dad died. Can still see his face, but can't seem to call up his voice anymore.

Every time I think I've got her pegged, something happens to remind me that Melinda may as well be from outer space for all I understand her.

“I know somebody who likes you,” I told her the next day at lunch.

She looked at me like I had shot her dog. “Don't mess with my head, Leo. You've seen what happens to people who mess with my head.”

“Do you want to know who it is, or not?”

“Well, obviously you're determined to tell me,” she said. “So go ahead.”

And when I gave her the name, she didn't even know who Gates was. She remembered him as Caleb Drewânobody's called him that since he first got his pudgy fingers on the keyboard of a laptop.

“That guy?”

She was annoyed. “Quit pulling my chain.”

“Honestâthe guy likes you! I'm telling the truth!”

“But he's one of

you

,” she argued. “The forces of steal-from-the-poor-and-give-to-the-rich. P.S.âhe doesn't even know me.”

I didn't want to admit that Gates was on to her secret Web identity. She'd think he was a stalker or something. “He admires you from afar. That happens, you know.”

“I would never date a Republican,” she said flatly.

“Well, if he asks you out, just say noâdon't make a political speech,” I pleaded. “He's a good guy, even if he has lousy taste in women.”

“Hey, I'm flattered. I'm the only thing he's looked twice at that doesn't have a forty-gig hard drive.”

Here's another example of the sheer audacity of the girl. In the middle of putting down

my

friend, she had the nerve to hit me up to tutor

her

friend Owen Stevenson in algebra.

“Forget it,” I told her. “If Gates's feelings mean nothing to you, Owen's algebra grade means even less to me.”

In an outraged instant, her black fingernail was positioned half an inch from my left eye. “You're homophobic!”

“I don't have a problem with Owen being gay!” I defended myself. “I have a problem with him thinking he's smarter than everybody else!”

“He's gifted,” she insisted. “And that doesn't just come from me. It comes from the state of Connecticut.”

“Then why does he need a tutor?”

“Math is his weakness.”

I snorted. “And English, history, geography, scienceâ”

“Not true!”

“He isn't even good at being gay. When's the last time you saw him with a boyfriend?”

“When's the last time we saw

you

with a girlfriend?” she shot back. “I guess you're not very good at being straight.”

I refrained from pointing out that if Melinda hadn't forced herself onto that boat trip, Shelby Rostov might very well be my girlfriend.

“You know how it is with Owen,” she persisted. “They make him take all honors courses. He doesn't have a choice.”

She was right about that. At the age of six, Owen had scored 180 on an IQ test, wowing his teachers and the Connecticut Department of Education. They'd slapped a “genius” classification on the poor kid that he just couldn't shake. It never occurred to anybody that maybe the 180 was a fluke. Owen was a bright enough guy, but he was never going to live up to all those expectations. Yet whenever he tried to switch out of honors everything, the school wouldn't let him. Connecticut still believed in its diamond in the rough. The diamond had no voice in the matter.

“He got a raw deal,” I conceded.

“You can help him,” she wheedled. “You're great at mathâMcAllister Scholarship, early acceptance to Harvardâ”

She talked me into it. I wasn't gullibleâI knew she was snowing me. She just plain bulldozed it through. Senior year, up to my nose in exams, with Harvard on the line if I couldn't maintain my grades, I was donating my free periods to tutoring the untutorable.

Owen allowed me to work with him. That's just the kind of guy he was. Of course, I wasn't

helping

him; we were studying together.

“I hear you've been having trouble with vectors.”

Owen looked me up and down. “That shirt isn't really a good style for you. You need a full collar to de-emphasize your Adam's apple.”

If my Adam's apple was big, it bulged to twice the size when I had to deal with Owen. “Let's just do this,” I grunted.

“Okay,” he agreed. “Explain to me the part you don't understand.”

That's how the lessons went.

I

wasn't tutoring

him. He

was tutoring

me.

Apparently,

I

had a mental block about vector kinematics. For three weeks, I explained it upside down and underwater. I might as well have been speaking Swahili.

Every day, Melinda asked me, “How's it going?”

And when I replied, “Not well,” the look she shot me clearly said that she blamed my failure on homophobia.

We tutored on. I can't say I didn't learn anything: my voice was a little too high; my pants were pleated when they should have been flat front; I could never be a hand model with knuckles like that. What I

didn't

learn was vectors, which was to say

he

didn't learn vectors.

At last, a breakthrough. Owen loved old-fashioned pinball machines. So I used the path of a pinball as it bounces around the game to represent vectors. Each bounce has distance and direction, and the algebraic tally of the vectors is the final position of the ball.

Sound familiar? It was my pinball theory. Of course, I never applied it beyond the field of algebra until after I'd learned the truth about McMurphy.

And he got it. I knew he got it, because he said, “I think you'll be just fine now.”

I bristled. “Hey, man, I knew this stuff already.”

“See what we can accomplish when we work together?”

“You're delusional,” I informed him.

But Melinda was pleased. And even though her opinion should have meant zero to me, I basked in it. I even checked Graffiti-Wall.usa to see if KafkaDreams mentioned my accomplishment. The closest thing I found was: