Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle (2 page)

Read Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle Online

Authors: Russell McGilton

January, 2001

I have never liked flying, and I was about to never like it even more. At 35 000 feet, this became abundantly obvious.

‘You are cycling from Bombay to Beijing?’ asked a rotund Indian man sitting next to me while Denzel Washington flashed across a small television screen above us in football gear. His name was Deejay and though his name might suggest something in the hip music world, he was in fact an IT consultant living in Sydney.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘But why? We have trains and buses there. Much easier for you, I think.’

‘Well, you see, cycling lets you delve into the lives of people you wouldn’t normally meet. You get to be one with the landscape, letting it wash over you.’

He snorted. ‘To be with the common man?’

‘Well, that’s part of it. I’m writing a book and I thought Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle would be an excellent title.’

‘Ah, the alliteration.’

‘Precisely. The bum-de-bum, bum-de-bum sound,’ I said, thumping my hand on each ‘b’ to stress the point.

‘Bombay to Beijing by Bicycle!’ He laughed, then sipped his tea thoughtfully. ‘Only …’

‘What is it?’

‘Bombay, my friend, is not Bombay anymore.’

‘What?’

‘This is the old name. It is now Mumbai.’

I gulped my scotch, spilling it down my chin. ‘Oh, sure. Right. I know. It’s just that in my guidebook it’s got “Mumbai slash Bombay”. I mean, doesn’t everyone still refer to it as Bombay? You know, when I was in Ho Chi Minh City the locals kept calling it Saigon. Or Myanmar still being referred to as Burma. You know, one and the same … interchangeable … well, aren’t they?’

‘No, no. It is Mumbai.’ He grinned then put on his headphones and went back to watching Denzel teach white boys how to tackle.

‘Mumbai …’ I said to myself. ‘Mumbai to Beijing by …’ I looked out at the escaping Australian desert, suddenly wanting to retrieve it.

‘Shit!’

***

The next morning I woke to the sound of the phone ringing.

‘Good morning, sir. Breakfast? Budda toast, omelette,

chai

. Vhot are you vanting?’

‘Could I please have the buttered toast,

chai

, omelette … jam?’

‘Okay.’

He hung up.

I opened the drapes. The sun was out, warming the run-down and mildewed buildings opposite, their window ledges chalked with pigeon shit. Dusty rainwater pipes ran this way and that like some alien mechanical creeper while a large yellow sheet, hung out to dry, tongued its way down a wall.

This was the daylight squalor I had imagined as I bounced around Mumbai’s traffic the previous night.

‘Sorry, sir,’ the taxi driver had said, swerving out of the way of a doorless bus. ‘Much traffic bumping. No good here in India. Many bad peoples driving without permission.’

I was in Colaba, a narrow peninsula of Mumbai bubbling with hotels, tourists, markets and restaurants by the sea. Under the morning sun, ragged men, dark as the rubbish around them, shovelled clumps of brown muck onto wagons pulled by water buffalo while business men briskly marched past, skipping over holes in the pavement as their leather briefcases pumped them towards towering office buildings. Women delicately tiptoed around a beggar sitting by a gift store, their gold and red saris floating around the women as if they were walking under water. Meanwhile, inside my hotel, a child exhausted itself into convulsive, tearful retches.

Mumbai sounded big, and with good reason. Over 16 million people live

iv

, work and breathe in this colliding metropolis. It has the biggest film industry in the world, more millionaires than New York, and a port that handles half of India’s foreign trade. Workers from Assam, Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan and even as far away as Nepal come here to make it big in this collective maelstrom, doing any work they can find. Many are unlucky and find themselves in one of the largest street slums of India, if not the world.

I turned on the air-conditioner and looked at the mess that had taken over my room: a Trek mountain bike: four panniers (bike bags), a handlebar bag and a medium-sized backpack. A total weight (bike included) of 43 kilograms

v

. While Dervla Murphy carried only a small kitbag of clothes, a handgun and a dash of courage, I felt it prudent to pack for the worst.

Just as I was considering all this the door burst open.

A porter, sweating in the humidity, charged in with breakfast, and put it on the table. This would be a common experience for me in India – staff walking in on me without a knock catching me in all sorts of undress not to mention compromising situations.

‘Welcome to Bombay, sir.’

‘Bombay? I thought it was called Mumbai?’

He smiled. ‘As you like.’

Deejay had been wrong, it seemed (or just winding me up). As I would find out later, Indians were still using the name Bombay quite liberally: taxi drivers asked where in Bombay I wanted to go to, students eagerly asked for my impressions of Bombay, restaurant owners praised Bombay epicure, hotel managers requested information on the duration of my stay in Bombay, and the local film industry was still referred to as Bollywood, not Mollywood.

Perhaps the new name hadn’t been embraced for political reasons. In 1996, Bombay’s name was changed to Mumbai after pressure on the Indian government from the ultra-right-wing Shivsena party, led by the prickly Bal Thackery. The name change was aimed at repelling legacies of India’s past colonisation and encroaching Westernisation. British names had been written over with Indian ones – street names, places and features of the city that lent reference to the Raj.

The smell of omelette took me from these thoughts and sat me down to breakfast, where I noticed that something was missing. Everything was there – the omelette, tea and toast …

‘Jam?’ I asked the porter, but he simply wobbled his head again and left.

What was with the head-wobble? Was it a ‘yes’, a ‘no’, ‘I don’t know?’ or ‘I’ll just keep you guessing’? It reminded me of those toy dogs you used to see in the back of old Chrysler Valiants, heads jiggling happily.

I bit into my omelette when a distinct sweetness hit my palate. ‘Oooh! They’ve mixed the jam in!’

With my jam-curried omelette hanging off my fork, I unfurled my Nelles map of India and China.

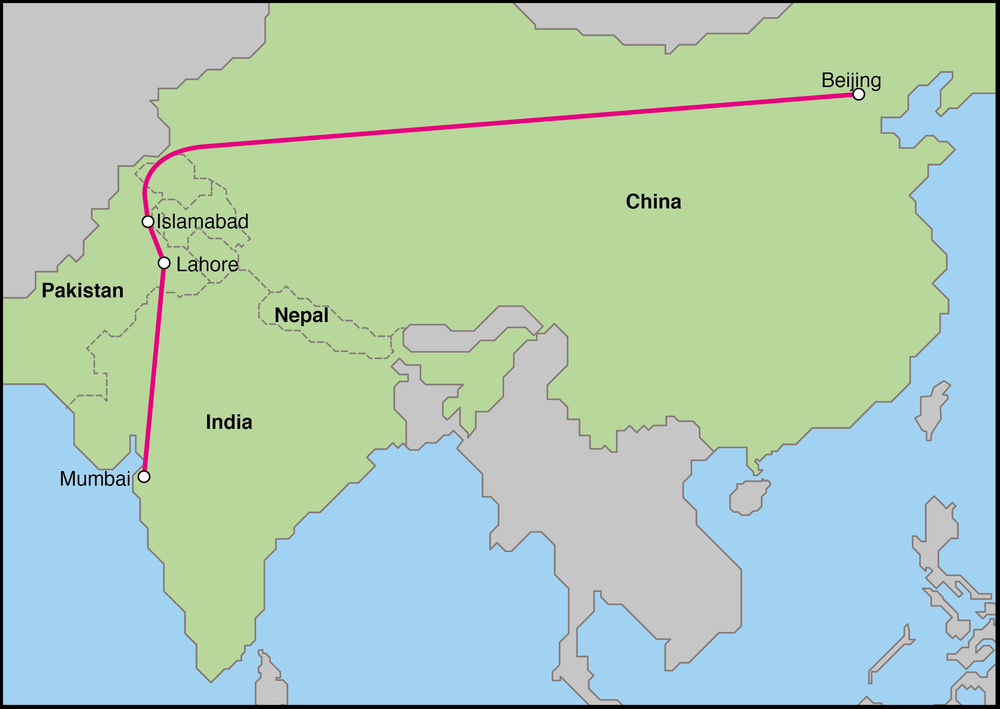

When I first decided to do this trip back in Melbourne, my plan was to start from Mumbai/Bombay, straight through to Nepal then into Tibet, China and eventually Beijing. However, the Chinese government were (and still are) a bit sensitive about independent foreign travellers, let alone cyclists, going through this border crossing (mmm … could it be the wholesale destruction of the Tibetan people and their culture that they don’t want us to see?), thus they were barred from passing. It was only on organised tour groups that this was possible.

So, my plan changed to China via Pakistan.

But this changed again when four months before I was about to leave, I fell in love.

A gorgeous blue-eyed blonde, Rebecca, a recently qualified acupuncturist and eight years my junior had caught me hook line and sinker. She too was going travelling, and as it was her first time, adamant about doing it on her own.

‘Besides,’ she had said, flicking through travel guides at the bookstore. ‘Europe’s more my thing. Not India.’

‘But just imagine Bec, there we are in an Indian palace, making love in the steamy monsoonal heat, while the rain trickled and danced outside and a cool breeze refreshed our hot naked bodies … mmm?’

‘Ooh! Now,

there’s

a thought!’

Of course, this wasn’t the only reason Bec eventually agreed. She wasn’t that kinda girl. Bec was going because she wanted to meet the people, learn about the history, to understand the cultural milieu and the colonial context in sub-continental India … actually, no, I think she was just going for the sex! Hell, it would be enough for me. ‘You wanna shag over a Indonesian volcano …

surrrreee

!’

‘Just say anywhere on my itinerary, Bec, and we can meet up there for a month and then you can do your own thing.’

She looked at the map and pointed to an obscure splog.

‘Kathmandu!? But that’s not on the way,’ I protested.

‘Yes, it is darling!’

And because women are always right, I made a ‘slight’ 3000-kilometre detour via Rajasthan (to beat the approaching summer).

This was my final plan:

Yes, I know. It makes Winston Churchill’s hiccup

vi

look like an epileptic seizure. But would you believe it got far worse?

***

After breakfast, I set to work on assembling the bike, most of that time spent straightening or ‘truing’, as it’s called, the front wheel (‘Thanks Qantas!’).

Dervla, before her big trip, christened her bike ‘Roz’. Not to be outdone, I called mine ‘bike’.

Once ready, I hauled ‘bike’ over my shoulder, walked downstairs and, with a stiff breath, threw myself into the maelstrom of traffic for my debut ride into Mumbai.

Of course, the first thing you notice about cycling in Mumbai is the traffic. In Melbourne, cyclists go on the far left of the road and cars go on the right. In India, well, it’s pretty much the same except the

cows

go on the far left and cars on the right.

The reason cows in India have such free rein of the roads, footpaths and in some cases (as I have seen) banks, is because of that well-known fact that they are considered – in India’s largest religion, Hinduism – to be sacred. In its religious texts cows are represented with their famous deities: Lord Rama, The Protector, received a dowry of a thousand cows; a bull was used to transport Lord Shiva, The Destroyer; while the Lord Krishna, The Supreme Being, was a humble cowherd. There are even temples built in honour of them.

Cows are so loved in India, Mahatma Gandhi went so far as to declare, ‘Mother cow is in many ways better than the mother who gave us birth’. Somehow, I don’t think mothers around the world would be impressed with Gandhi’s comparison, i.e. being upstaged by some dozy, garbage-eating ruminant with hairy teats.

Anyway, it is no wonder that it is illegal to eat or harm cows in most states of India.

Now the problem with all this … this overt bovine respect, is that the cows, people, the cows …

know

this! And let me tell you something – they are the rudest and most arrogant cows (apart from the ones in public office) that I have ever met in my entire life!

They just lurch out in front of you like a second-hand couch falling off a truck without so much as a cursory look. So many times I’ve had to slam on the brakes to narrowly miss their voluminous rumps or have been ‘nosed’ off the pavement for being in their way. I’ve even seen gangs of them plonking down in the middle of traffic like some grazing roundabout. I tried to exact some kind of revenge by going to McDonalds but to my dismay they only sold mutton burgers.

Despite the cows, cycling in Mumbai wasn’t as dangerous as I had thought, even if there didn’t seem to be enough space for anything other than taxis, crammed buses and the occasional gnat. Traffic moved a lot slower due to there being so much of it and drivers showed no sign of agitation as they beeped madly at seemingly everything around them.

It was, however, pollution that caused me the greatest of ills. Most drivers adulterated the fuel of their cars, auto-rickshaws, motorbikes or trucks with kerosene, as kerosene is much cheaper than petrol. Try as I might to block out the foul mess with a folded handkerchief over my face, this only served to scare American Express staff when I went to cash a traveller’s cheque.

I thought I’d go and see the Parsi Towers of Silence situated on Malaba Hill, a lush enclave of Mumbai some 5 kilometres away. For over 2500 years Parsis have been disposing of their dead in

dokhmas

(towers). In these towers, corpses are laid out naked and arranged according to age and sex, and are later … devoured by vultures.

As I cycled into the thicket of street life along Colaba Causeway, my nose was assaulted by a confluence of smells: the heavy stench from open drains, the odour of stale urine, the relieving aroma of

pakoras

(fried vegetables) from street vendors, and for contrast, the overpowering perfume from joss sticks placed like guards on the corner of erected tables selling bluish pictures of the Hindu monkey god, Hanuman.