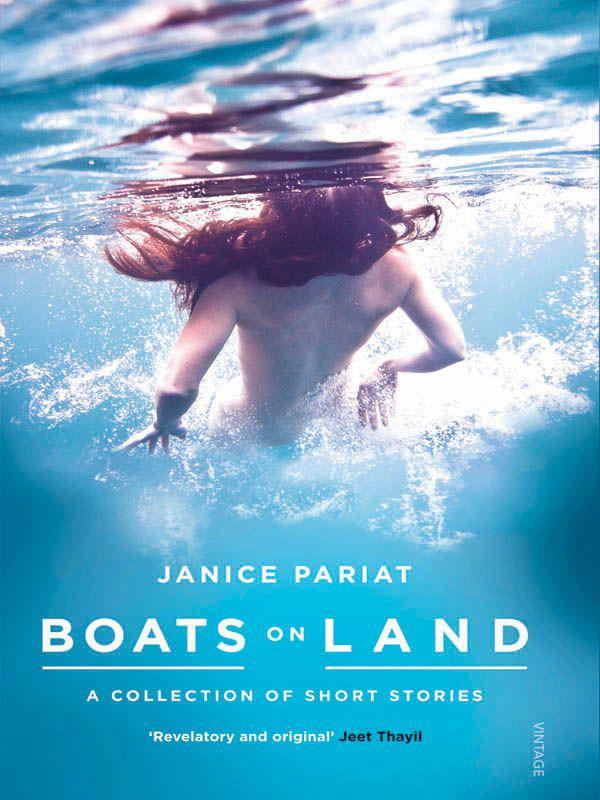

Boats on Land: A Collection of Short Stories

Read Boats on Land: A Collection of Short Stories Online

Authors: Janice Pariat

Published by Random House India in 2012

Copyright © Janice Pariat 2012

Random House Publishers India Private Limited

Windsor IT Park, 7th Floor, Tower-B

A-1, Sector-125, Noida-201301 (UP)

Random House Group Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road

London SW1V 2SA

United Kingdom

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 9788184003390

For my parents

I found the marvelous real with every step.

—Alejo Carpentier

Contents

1. A Waterfall of Horses

2. At Kut Madan

3. Echo Words

4. Dream of the Golden Mahseer

5. Secret Corridors

6. 19/87

7. Laitlum

8. Sky Graves

9. Pilgrimage

A Waterfall of Horses

H

ow do I explain the word?

Ka ktien.

Say it. Out loud. Ka ktien. The first, a short, sharp thrust of air from the back of your throat. The second, a lift of the tongue and a delicate tangle of tip and teeth.

For I mean not what’s bound by paper. Once printed, the word is feeble and carries little power. It wrestles with ink and typography and margins, struggling to be what it was originally. Spoken. Unwritten, unrecorded. Old, they say, as the first fire. Free to roam the mountains, circle the heath, and fall as rain.

We, who had no letters with which to etch our history, have married our words to music, to mantras, that we repeat until lines grow old and wither and fade away. Until they are forgotten and there is silence.

How do I explain something untraceable? The perfect weapon for a crime. Light as pine dust. Echoing with alibis. Conjuring out of thin air, the ugly, the beautiful, the terrifying.

Eventually, like all things, it is unfathomable. So, how do I explain?

Perhaps it’s best, as they did in the old days, to tell a story.

I learnt about the word long ago, when I was young and had seen no more than thirteen winters. In those days, the nights were so cold that frost gathered on our roofs and gardens like snow. Well, that’s what the bilati men said it looked like, for we had never seen snow in all our lives. They would huddle by the fire at the gate to Sahib Jones’s bungalow and talk about their homes far away across the sea. I would bring wood and coal to bolster the flames, and eavesdrop; they paid no attention to this dark, snotty-nosed boy in his threadbare clothes and frayed woollen shawl. They’d speak of places I’d never heard of, names that slipped through my memory like little silver doh thli I tried to catch in the streams. I dreamt about it sometimes, the land of gently rolling hills, thatch cottages, and women white as the ‘tiew khlaw that grew wild by the roadside. The bilati men had come to guard the land and tea plantation of an owner we hardly saw; their presence there forever changed the lives of the people of Pomreng village.

It was the 1850s, and Pomreng was a smudge that probably couldn’t be found on any map of the area at the time. It lay nestled on a bit of grassy flatland, a cluster of fifty huts, ribboned by a river that flowed languid and deep before plunging down a steep rocky cliff. Shillong, then called Laban, lay at the end of a rough, day-long, horse-cart journey on a dirt track twisting through forested hills or miles of desolate countryside. Our people rarely ventured out except for the occasional family visit or trip to the big market. Nothing ever happened at Pomreng; it was a quiet life, marked by sowing and harvests, steady as the seasons. Which was why there was great excitement at the news that a judge from Sylhet had bought vast swathes of land outside our village, to grow tea and build himself a pleasure palace full of wondrous things. ‘The ceiling will be high as the trees,’ it was reported. ‘They’re bringing maw-Sohra all the way here for the floors.’ It would have a hundred rooms and a hundred servants. Eventually, the palace turned out to be a humble lime-washed, stone bungalow atop a hillock, with a smaller cottage and sheds and stables further down the slope. But we weren’t disappointed; it was still the largest construction we’d ever seen. The judge arrived with his family on a short vacation at the end of the monsoon, and departed soon after, but they left behind a unit of soldiers and their horses. The estate was managed by a missionary named Thomas Jones, and rumour had it that he was on the run from a rascal bilati businessman in Sohra who wanted him hanged for encouraging the locals to question the price of his goods. We didn’t know if that was true, but Sahib Jones did look perpetually worried, his sombre face pale as a stub of bitter white radish. He strode around dutifully inspecting the tea bushes and large garden, checking every once in a while on the men and their animals, yet there hung about him an air of nervous disquiet.

My young mother worked as a maid for his wife Memsahib Greta, which was how I ended up employed as help around the house and estate, doing various odd jobs and running errands. I didn’t mind; we needed every bit of spare cash since my father walked out on his wife and five children one night in a drunken fury and never returned. I also worked extra hard because my secret ambition was to some day get out of Pomreng and make my way to Shillong. If I could, I would take my mother and siblings with me. The little money I saved I hid in an old sock under my mattress. Every morning, I’d crawl out of bed as dawn broke outside our shuttered windows, bathing the hills in milky white light, and head to Sahib Jones’s kitchen, a stone building separate from the main house, where my mother would be preparing sweet red tea in a large blackened kettle. From there I’d carry the cups on a tray out to the men—first the ones who’d been up all night at the gate, and then to the others. After a while, I came to know them well—Pat, a big man the size of a bear; Roger, the one with blazing orange hair; Trotter, a stout red-faced soldier with the loudest voice in camp; and Sahib Sam, the only one who thanked me when I handed him his cup of tea. I marvelled at the strangeness of their skin, their eyes like bits of coloured glass, the unfamiliar intonations of their language. Even their smell, I thought, was different. I wondered why they’d given up their homes and families to protect a cold, muddy slice of land in a place they couldn’t possible care about. But as Mama Saiñ, the village headman, said, it was the bilati men with their guns and cannons who ruled us, and hence this was their territory too. Besides, he added, they were also probably people on the run, like Sahib Jones, who found shelter and safety in Pomreng’s isolation. I wouldn’t have been surprised to discover that Trotter, Pat and some of the others were criminals—they were rough, filthy-mouthed men who grew more garrulous and aggressive by the day. Sometimes I saw them whip the plantation workers or knock them down with their horses.

‘Move, you bastards,’ they’d shout. ‘Get to work before we peel the flesh off your bones.’

I was petrified of them and kept out of their way as much as possible. Since I was small and insignificant, it wasn’t too difficult to slip past them unnoticed. I did quite well until one morning when I tripped while carrying a tray, and spilled hot tea on Trotter’s lap.

‘Bastard,’ he yelled, jumping up from the moora, and cuffing my ear so hard I fell to the ground bleeding. He was about to strike again when suddenly a pair of legs in muddy black boots appeared in front of me.

‘Leave the boy alone, Trotter, it was an accident.’ It was Sahib Sam.

‘Burnt my balls, the little son of a bitch.’

‘That’s good to know, Trotter. Some of us were worried you didn’t have any.’

The laughter that followed drowned out Trotter’s belligerent shouts.

‘Are you alright there, boy?’ A pair of bright blue eyes looked into mine. Sahib Sam had bent over me, his hand on my shoulder. I nodded, too scared to speak, and as soon as I was on my feet, I ran like I was being chased by a wild animal.

From that time on, I saved the largest cup of tea for Sahib Sam, and the choicest piece of meat for his dinner, the sweetest ‘pu khlein cakes bought from our local market, and the largest, driest logs of wood for whenever he was on night duty. As captain of the unit he had probably warned Trotter as well, for apart from a string of verbal abuses if I happened to pass by, the red-faced pig left me alone.