Blow Out the Moon (20 page)

In America, I knew cat’s cradle up to this one — but in England, I learned lots more moves. The hardest one was called tramlines: two straight lines that you hooked with your little fingers. Cat’s cradle was really fun; it was so satisfying when you learned how to do it well enough so that it could just keep going and going!

And of course we talked a lot. That was one of the most fun things about Sibton Park — how much everyone talked and that there was always someone to talk to. And we read (to ourselves, never out loud). We read books, and some people had comic books that told stories. There was one called “Angela Airhostess” about a beautiful stewardess and her adventures, though I didn’t like what it said about America: “In New York she fell in with a fast, Scotch-drinking crowd.” The Americans all wore hideous blue-green suits and talked roughly.

Those times in our study were cozy. Only our class was allowed in without permission — even teachers and Matron had to knock on the door and ask. We usually didn’t let anyone else in: It was a place just for us. I liked it a lot.

Even though there was no fireplace or heat, it was never cold (probably because there were fourteen of us, and also because we usually sort of cuddled when we were just sitting around). One of the cubby cupboards went almost up to the ceiling; we climbed on top of it by standing on the table and then sort of pulling and scrambling up. When we sat on that, our heads touched the ceiling unless we slumped a little.

The other cubby cupboard stood under the window; when you pressed your face against the pane, all you could see was black, even though the Tudor Garden was right outside. You couldn’t see any of the paths or even the sundial. Sometimes, instead of talking, I sat on top of it and wrote stories, and as Hobby Day got closer, I sat there every day and worked on “The Richardsons.”

Finally, it was finished: thirty-two pages — on big, almost American-sized paper, not composition book pages. I read the whole thing out loud. Some people just sat and listened; some people went on with jacks and cat’s cradle; but everyone listened, no one seemed bored, and several people commented on how long it was.

“Thirty-two pages! I expect you really WILL be a writer when you grow up.”

I hoped that meant they thought it was GOOD, and not just — long. But more than that, I hoped that when Marza saw it on Hobby Day, she would read it — and that when she read it, she’d think it was good.

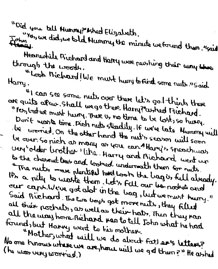

A page from “The Richardsons,” the thirty-two-page story I wrote.

Marza, a Great Lady

I was proud of my writing and I did show off about it a little, but in an English way.

Once, I was washing my hands in the cloakroom (they were blue all over with ink) and an older girl said, “Libby Koponen! Your hands! Whatever have you been doing?”

“Just writing,” I said airily, in a very English way.

She thought that was funny and repeated it to everyone else: “ ‘Just writing!’ says Libby.”

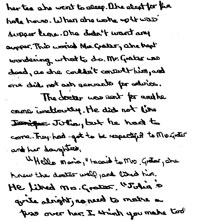

Part of the story I read.

Everyone knew I wanted to be an author when I grew up, and some people read what I wrote and said it was good. I wrote some more stories about The Crazy Old Witch (I only let Clare read those; they were too childish and too American for the others). To the others, I read a story about an English girl who had been ill and never had many friends until she went to school and learned how to ride.

But “The Richardsons” was by far my longest and, I thought, my best story.

It told about all the things the family did in the forest during the war, including all the children’s complaints and arguments, and ended with: “The Germans were out of that part of England and Mr. Richardson was home at last!”

After I read it out loud to everyone that day in the study, I copied it over neatly, in ink, in my best handwriting, and gave it to Miss Tomlinson for Hobby Day.

As we walked around the art room on Hobby Day, looking at the things everyone had made, I wondered, again, what Marza (who was about the only person in the school who hadn’t read it) would think.

She didn’t say anything when she saw the story, but when she left the Art Room, she took it with her.

The next day after prayers she said she wanted to see me in her office. Usually, only seniors were called in there, and even they weren’t called in often. Everyone looked at me, wondering.

When I went in, she was at her desk, sitting up very straight. She motioned for me to stand right next to her, so I did. My story was on the desk in front of her. I was standing so close to her that I could see right into her eyes. I was a little scared — they looked so serious.

“I read your story,” she said, “and it was a good story. However — you made one mistake.”

My throat started to hurt the way it does when you’re about to cry and trying hard not to. I’d been so proud of the story and I had wanted her to like it so much and she didn’t — I’d said something terrible, wrong, I could tell by the way she was looking at me.

She drew herself up proudly, like a queen, and said, “The Germans

never

landed in England.”

I started to cry — I didn’t know why saying they had was so bad, but I understood that it was a terrible thing to have done.

“No foreign army has ever invaded us,” she said. “They have often tried; they have never succeeded.”

She talked more and said a poem about “this little world, this precious stone set in a silver sea” and “moat” and “this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.”

I tried to stop crying and listen properly but I couldn’t. I’d wanted that story to be good so badly. She stopped talking and pulled me onto her lap.

I stopped crying. I sat up straight and pulled my handkerchief out of my sleeve (in England all children carry handkerchiefs tucked into the sleeve of their jumpers). Marza looked at it and I did, too: a crumpled ball, wet in some places, stiff yellow-green in others. Gently, she tucked it back into my sleeve.

“Most wet and uncomfy,” she said.

She handed me a clean one and I blew my nose and dried my eyes and the rest of my face.

“There, that’s better, isn’t it?” Marza said. She smiled and gave me a little squeeze. “Off you go — and it IS a good story, you know.”

When I walked back to my form room I felt proud of my writing again. “The Richardsons”

was

a good story. Marza liked it.

And I thought about the rest. It was odd — I never would have thought of Marza as cuddling anyone. She didn’t make me feel embarrassed about crying, or the handkerchief — it must have looked disgusting to her, but she didn’t make a face or a disgusted comment; she acted as though it — and my crying — were perfectly all right. That’s what being truly polite means: thinking about how other people feel and acting in the way that will make them feel best.

Before that, I had admired Marza, but I had been a little bit afraid of her, too. From then on, I wasn’t afraid of her anymore, maybe in awe of her — she was a true lady. And after that, whenever I heard or read the phrase “a great lady,” I thought of her.

Riding on the Downs

It was almost spring again and we were riding on the downs. The “downs” are little hills with no trees, just grass open to the sky. They look like the hills you draw when you’re little. We were racing to Miss Monkman, who was on top of a hill; she’d told us to stand still until she got there and that when she raised her arm we could start — and we could go as fast as we wanted to when we were going uphill; going down we had to walk or trot.

As soon as Frisky and I got to the bottom and the ground was flat, I squeezed with my legs to make him go faster and he bounded into a canter. The grass felt short and springy. My feet were in the stirrups, my heels pushed down, my ankles acted like springs every time he bounded forward — but the rest of me stayed still except for my hips, which sank down into the saddle and moved back and forth in rhythm with his canter. I’d finally learned to canter and I loved it. It’s hard to describe what cantering feels like but I’ll try.

Your legs grip the horse, your calves especially, and your hipbones move one TWO three (and then a little pause while the horse is in the air for a second), one TWO three (the little flying pause again). Your legs don’t move, your upper body doesn’t move — just your hips. Your hands are kind of pressing into the rough mane; they don’t move, either, but your elbows bend in rhythm, too.

When we got to the top of the hill, I squeezed the reins and gripped hard to make him slow down: it’s a little scary going fast downhill — you feel off-balance, as though you might slip out of the saddle and slide right down the pony’s neck, And anyway it was against the rules of the race.

So we walked down but when we got to the bottom he jumped into the canter as soon as I squeezed — and up the last hill we galloped. In a gallop your hips don’t move: you stand up in the stirrups a little bit and you feel the pony stretch out and jump, stretch out and jump, faster and faster, over and over … the rhythm isn’t smooth like the canter, and it’s so fast. You feel almost like the pony’s taking little jumps into the air, pushing and pulling and stretching himself with each foot, and the hooves on the ground are so loud. Frisky wanted to win as much as I did, I could feel it. We went faster and faster — it was almost hard to breathe. I just stood up in the stirrups and looked straight between his ears at Miss Monkman until we got there.

We were first.

“Well done, Libby!” she said, and I patted Frisky and felt proud.

I’d worked hard at my riding and, even though almost all the other girls were better at it than I was, I still felt proud that I’d learned how to do it.

And I loved it. Nothing is as much fun as riding your best on a good horse. That day the air was wet, with that muddy late-winter, almost-spring feeling, and I

was

riding my best. My body was doing everything I wanted it to do all by itself. Without my even thinking, it moved in perfect rhythm with Frisky.

Maybe, I thought, next term I’d learn to jump; and then I remembered that I wouldn’t be there next term.

“God Save the Queen!”