Bloody Crimes (26 page)

Not all of Harrington’s correspondents demanded special favors. Some offered helpful advice. “Pardon me for suggesting that as few carriages as possible ought to be allowed in the funeral cortege of the President. There are one hundred thousand aching hearts that will be following his remains to the grave. This cannot be done if long lines of vehicles occupy the space, without adding to the volume of humanity desirous of participating.” The anonymous letter was signed “Affectionately.” The same writer also sent a note to Stanton on April 18 suggesting that streetcar noise might disturb the next

day’s funeral events: “The running of cars upon the street railroads, between 17th Street and the Congressional Cemetery, should cease tomorrow between 11 a.m., and 4 p.m. The rolling of cars, and the jingle of bells will contrast strangely with the solemnity of those sacred hours.”

As the final visitors filed past the coffin, carpenters loitered nearby, impatient to start work the moment the last citizen exited the White House and the doors were shut and locked behind them. If the public had its way, the viewing would have continued through the night. Thousands of people were turned away so the crews could begin preparing the East Room for the funeral. Disappointed mourners would have one more chance to view the remains, after they were transferred to the Capitol.

Harrington had come up with an ingenious solution to the seating dilemma. He would not seat the guests in chairs at all. He had calculated that, allowing for the space required for the catafalque and the aisles, it was impossible to squeeze six hundred chairs into the East Room. He decided that only a few of the most important guests, including the Lincoln family, needed to have individual chairs. But if he built risers, or bleachers, for the rest, he could pack slightly more than six hundred people into the East Room, the minimum number of important guests he needed to seat. The White House was abuzz with activity—men carried stacks of fresh lumber into the East Room, where carpenters sawed, hammered, and nailed them into bleachers.

O

n the morning of April 19, cities across the North prepared to hold memorial services at the same time as the Washington funeral. Military posts across the nation marked the hour. At the White House, journalist George Alfred Townsend was among the first guests to enter the East Room that morning. As one of the most celebrated members of the press, he was allowed to approach Lincoln’s corpse. His account of the event invited his readers to do the same:

Approach and look at the dead man. Death has fastened into his frozen face all the character and idiosyncrasy of life. He has not changed one line of his grave, grotesque countenance, nor smoothed out a single feature. The hue is rather bloodless and leaden; but he was always sallow. The dark eyebrows seem abruptly arched; the beard, which will grow no more, is shaved close, save for the tuft at the short small chin. The mouth is shut, and like that of one who has put the foot down firm, and so are the eyes, which look as calm as slumber. The collar is short and awkward, turned over the stiff elastic cravat, and whatever energy or humor or tender gravity marked the living face is hardened into its pulseless outline. No corpse in the world is better prepared according to its appearances. The white satin around it reflects sufficient light upon the face to show that death is really there; but there are sweet roses and early magnolias, and the balmiest of lilies strewn around, as if the flowers had begun to bloom even in his coffin…

Three years ago, when little Willie Lincoln died, Doctors Brown and Alexander, the embalmers or injectors, prepared his body so handsomely that the President had it twice disinterred to look upon it. The same men, in the same way, have made perpetual these beloved lineaments. There is now no blood in the body; it was drained by the jugular vein and sacredly preserved, and through a cutting on the inside of the thigh the empty blood-vessels were charged with a chemical preparation which soon hardened to the consistence of stone. The long and bony body is now hard and stiff, so that beyond its present position it cannot be moved any more than the arms or legs of a statue. It has undergone many changes. The scalp has been removed, the brain taken out, and the chest opened and the blood emptied. All that we see of Abraham Lincoln, so cunningly calculated in this splendid coffin, is a mere shell, an effigy, a sculpture. He lies in sleep, but it is the sleep of marble.

All that made this flesh vital, sentient, and affectionate is gone forever.

The morning of the funeral, requests were still being made by politicians and leading citizens hopeful that the funeral train would pass through their locale. C. W. Chapin, president of the Western Railroad Corporation, sent an urgent telegram to Massachusetts congressman George Ashmun, one of the last men to see Lincoln alive at the White House the evening of April 14, pleading with him to use his influence to divert the funeral train to New England: “In no portion of our common country do the people mourn in deeper grief than in New England,” he wrote. “This slight divergence will take in the route the capital of Connecticut and also important points in Massachusetts.”

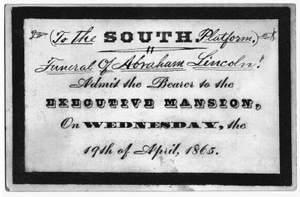

To thwart gate-crashers, funeral guests were not allowed direct entry to the Executive Mansion. Instead, guards directed the bearers of the six hundred coveted tickets, printed on heavy card stock, next door, to the Treasury Department. From there they crossed a narrow,

ONE OF THE FEW SURVIVING INVITATIONS TO LINCOLN’S WHITE HOUSE FUNERAL.

elevated wooden footbridge, constructed just for the occasion, that led into the White House. A funeral pass became the hottest ticket in town, more precious than tickets to Lincoln’s first and second inaugural ceremonies or balls, and more desirable than an invitation to one of Mary Lincoln’s White House levees. The only ticket to surpass the rarity of a funeral invitation had not been printed yet and would be for an event not yet scheduled—the July 7, 1865, execution of Booth’s coconspirators, for which only two hundred tickets would be issued.

Just hours before the funeral, George Harrington was still receiving last-minute ticket requests: “Surgeon General’s Office / Washington City, D.C. / April 19. / Dear Sir / Please send me by [messenger] tickets for myself & Col. Crane my executive Officer. JW Barnes, Surgeon General.” Harrington could not deny tickets to the chief medical officer of the U.S. Army and senior doctor at the Petersen house, or to his deputy.

As the guests entered the Executive Mansion, none of them knew what to expect. The East Room overwhelmed them with its decorations and flowers and the catafalque. It was an unprecedented scene. Two presidents had died in office, William Henry Harrison in 1841 and Zachary Taylor in 1850, but their funerals were not as grand or elaborate as this. No president had been so honored in death, not even George Washington, who, after modest services, rested in a simple tomb at Mount Vernon.

The scene lives on only in the written accounts of those who were there, and in artists’ sketches and newspaper woodcuts. Somebody should have taken a photograph. Sadly, no photographs were made in the East Room before or during the funeral. It could have been done. Alexander Gardner had photographed more complex scenes than this, including the second inaugural, where he took crystalclear close-ups of the East Front platform and one of his operators had managed to take a long view of the Great Dome while Lincoln

was reading his address. Edwin Stanton failed to invite Gardner or his rival Mathew Brady to preserve for history the majesty of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral.

At exactly ten minutes past noon, a man arose from his chair, approached the coffin, and in a solitary voice broke the hush. The Reverend Mr. Hall intoned the solemn opening words of the Episcopal burial service: “I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord; he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live; and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.”

Then Bishop Matthew Simpson, who had arrived on time, spoke. He was followed by Lincoln’s own minister, the Reverend Dr. Gurley, who delivered his sermon.

It was a cruel, cruel hand, that dark hand of the assassin, which smote our honored, wise, and noble President, and filled the land with sorrow. But above and beyond that hand, there is another, which we must see and acknowledge. It is the chastening hand of a wise and faithful Father. He gives us this bitter cup, and the cup that our Father has given us shall we not drink it?

He is dead! But the God whom he trusted lives and He can guide and strengthen his successor as He guided and strengthened him. He is dead! But the memory of his virtues; of his wise and patriotic counsels and labors; of his calm and steady faith in God, lives as precious, and will be a power for good in the country quite down to the end of time. He is dead! But the cause he so ardently loved…That cause survives his fall and will survive it…though the friends of liberty die, liberty itself is immortal. There is no assassin strong enough and no weapon deadly enough to quench its inexhaustible life…This is our confidence and this is our consolation, as we weep and mourn today; though our President is slain, our

beloved country is saved; and so we sing of mercy as well as of judgment. Tears of gratitude mingle with those of sorrow, while there is also the dawning of a brighter, happier day upon our stricken and weary land.

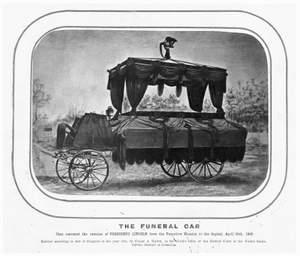

While the three ministers held forth for almost two hours, more than a hundred thousand people waited outside the White House for the funeral services inside to end. In the driveway of the Executive Mansion, six white horses were harnessed to the magnificent hearse that awaited their passenger. Nearby, more than fifty thousand marchers and riders had assembled in the sequence assigned to them by the War Department’s printed order of procession. Another fifty thousand people lined Pennsylvania Avenue between the Treasury building and the Capitol. According to the

New York Times,

“the throng of spectators was…by far the greatest that ever filled the streets of the city.”

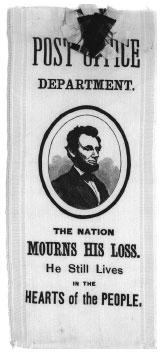

MOURNING RIBBON WORN IN WASHINGTON BY POST OFFICE WORKERS FOR THE APRIL 19, 1865, FUNERAL PROCESSION.

Most of the people outside the White House wore symbols of mourning: black badges containing small photographs of Lincoln, white silk ribbons bordered in black and bearing his image, small American flags with sentiments of grief printed in black letters and superimposed over the stripes, or just simple strips of black crepe wrapped around coat sleeves. Some mourners had arrived by sunrise to stake out the best viewing positions. By 10:00 a.m. there were no more places left to stand on Pennsylvania Avenue.

THE HEARSE THAT CARRIED LINCOLN’S BODY DOWN PENNSYLVANIA AVENUE.

Faces filled every window, and children and young men climbed lampposts and trees for a better view. The city was so crowded with out-of-towners that the hotels were filled and many people had to sleep along the streets or in public parks.

By the time the White House funeral services ended and the procession to the Capitol got under way, the people had been waiting for hours. It was a beautiful day. Four years earlier, on inauguration day, March 4, 1861, General Winfield Scott had placed snipers on rooftops overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue to protect president-elect Lincoln, who had received many death threats from boastful would-be assassins. No marksmen were needed today. This afternoon the only men on rooftops were spectators seeking a clear view of Lincoln’s hearse.