Bloody Crimes (20 page)

While the morticians embalmed and dressed Lincoln’s corpse, Benjamin Brown French dined at home at 3:00

P.M

. His headache was worse. He thought of his diary. He did not want to let the events of this day pass without committing them to writing in his thick, quarto-sized, leather-bound journal. But he couldn’t concentrate, so he went to bed. He slept until 7:00

P.M.

, then rose, took tea, and opened his diary. What he wrote that night and in the days to come, in his distinctive, beautiful script, fills the pages of one of the great American journals.

Lincoln’s corpse was ready for burial, but it was unclear where that would occur. Mary had the right to choose the site, but given her mental state, she was in no condition to discuss the subject only hours after her husband’s death. Edwin Stanton would confer with her and Robert Lincoln later. In the meantime, whatever the final destination of the president’s remains, official funeral events would have to take place in the national capital within the next few days. Stanton may

have had time to supervise the dressing of Lincoln’s body, but he had no time to plan and supervise a major public funeral, the biggest, no doubt, that the District of Columbia had ever seen. The secretary of war needed to delegate this responsibility, and there were several qualified candidates. Ward Hill Lamon, marshal of the District of Columbia, had known Lincoln for years, ever since their days as circuit-riding Illinois lawyers. Lamon had accompanied the president-elect on the railroad journey from Springfield to Washington in 1861 and had appointed himself the president’s unofficial bodyguard. Lamon, a big, strong, barrel-chested man, was once found sleeping outside Lincoln’s door at the White House clutching pistols in both hands. And it was Lamon who had organized the procession at Gettysburg on November 19, 1863, when Lincoln spoke there at the dedication of the national cemetery.

On less than a week’s notice, Lamon had planned everything, devised and printed the order of march and program of events, recruited U.S. marshals from several other states to assist him, and stood on the platform with Lincoln and announced to the crowd in his bellowing voice, “Ladies and gentlemen, the president of the United States!” But Lamon was in Richmond the night of the assassination and still had not yet returned to Washington. Stanton would have to select someone else.

Benjamin Brown French was another obvious choice. The old Washington veteran had been on hand for decades of historic events, including the deaths of other presidents, and a multitude of public ceremonies and processions. French was perfect but he was needed to play another role—decorator in chief of the public buildings, especially at the U.S. Capitol, where without doubt Lincoln’s corpse would lie in state.

Lincoln was, in addition to chief executive, commander in chief of the armed forces, and if Stanton wanted to entrust planning the funeral events to a military officer, he had several options. Major General Montgomery Meigs, quartermaster general of the U.S. Army,

was a master planner with superb organizational skills. Stanton relied on him to supply the entire Union army with muskets, uniforms, blankets, food, and more, and to deliver those goods wherever and whenever needed. But the war was not over, and Stanton could not spare Meigs from his vital mission.

There was Brigadier General Edward D. Townsend, the brilliant assistant adjutant general of the army. Townsend had served the legendary General Winfield Scott, hero of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, who in 1861 still held command of the army at the start of the Civil War. Upon Scott’s resignation, Lincoln, who knew Townsend’s qualities, offered him his choice of spots: “On reporting to the President, he asked what I desired. I replied I did not think it right to indicate for what duty I was most required, but was ready for any orders that might be given me.”

Townsend hoped for a field command, but the new general in chief, George B. McClellan, said that he was too valuable in army administration. Townsend served under Lincoln’s first secretary of war, Simon Cameron, and when he resigned the new secretary, Edwin M. Stanton, kept Townsend on, relying on him to run the adjutant general’s office during the extended absences of its titular head, General Lorenzo Thomas. Townsend whipped the office into shape and was willing to stand up to the formidable Stanton, thereby earning his respect. He would be a good choice to plan the funeral. But already Stanton had Townsend in mind for a special duty of utmost importance, one even more critical than planning the president’s funeral in the nation’s capital. He held Townsend in reserve.

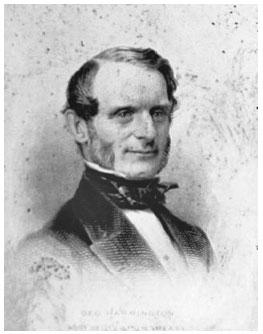

Stanton turned to another government department and considered George Harrington, assistant secretary of the Treasury. Harrington, fifty years old, was experienced in the ways of Washington. He had served as a delegate from the District of Columbia to the Republican National Convention of 1860 and had won the confidence of Lincoln’s second secretary of the Treasury, William P. Fessenden. Lincoln, Stanton, and all the other members of the cabinet

GEORGE HARRINGTON, THE MAN WHO PLANNED THE LINCOLN FUNERAL EVENTS IN WASHINGTON.

knew Harrington, and on occasions when Fessenden was absent from Washington, Lincoln had appointed him acting secretary of the Treasury. Upon Fessenden’s resignation in 1865, Harrington continued to serve under the new secretary, Hugh McCulloch. Stanton believed that Harrington had the keen, quick, and thorough organizational mind essential for this assignment and chose him to take charge of all Washington events honoring the late president.

Harrington accepted the appointment, which involved more than merely taking charge of events. It was up to him to conjure how the national capital should honor its first assassinated president. Two presidents, William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor, had died in office, but they had expired from natural causes during peacetime, not from murder at the climax of a momentous civil war. Their more

modest funerals were of limited value in planning Lincoln’s. It had been only five years since Harrington and his fellow delegates had nominated Lincoln at the Chicago convention of May 1860.

Once Harrington got to work, Stanton could focus on what should be done with Lincoln’s corpse after the Washington, D.C., ceremonies. Would the president be interred at the U.S. Capitol, in the underground crypt below the Great Dome, once intended as the final resting place for George Washington? Or would Mary Lincoln take the body home to Illinois, for burial in Chicago, its most important city, or in Springfield, the state capital and the Lincolns’ home for twenty-four years?

O

n Saturday afternoon, the autopsy doctors, witnesses, and embalmers departed the Guest Room, leaving Lincoln’s body alone on an undertaker’s board. Now he would repose in the Executive Mansion for three days and two nights, dressed in the same splendid clothes he wore on March 4, 1865, when he rode in a carriage in a grand procession from the White House to the Capitol, where he swore to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. On that great day the breast pocket of his suit contained a folded sheet of paper bearing 701 words. “With malice toward none,” he said from the marble steps at the East Front of the Capitol. “With charity for all,” he beseeched, “let us bind up the nation’s wounds.” Now, six weeks later, his suit pocket was empty. Few visitors were permitted to view the body until the remains would be carried downstairs to the East Room on April 17 in preparation for opening the Executive Mansion to the public the next morning. Before then only relatives, close friends, and high officials crossed the threshold of his sanctuary and intruded upon his rest.

Mary Lincoln’s confidante Elizabeth Keckly was one of them. After the president was shot, Mary had sent a messenger from the Petersen house summoning Keckly to her side. Elizabeth mistak

enly rushed to the White House, but guards there denied entrance to the free black woman, and she did not gain admittance until the next day. The very sight of Lizzie, as Mary affectionately called her, soothed some of the widow’s pain. They talked, and Mary told Lizzie about her terrible night at Ford’s Theatre and the morning at the Petersen house. Keckly comforted her and then asked to see Abraham Lincoln.

“[Mrs. Lincoln] was nearly exhausted with grief,” Keckly remembered, “and when she became a little quiet, I received permission to go into the Guest Room, where the body of the President lay in state. When I crossed the threshold…I could not help recalling the day on which I had seen little Willie lying in his coffin where the body of his father now lay.” Three years earlier Keckly had helped wash and dress Willie’s body. “I remembered how the President had wept over the pale beautiful face of his gifted boy, and now the President himself was dead.” Keckly lifted the white cloth shrouding Lincoln’s body. “I gazed long at the face,” she said, “and turned away with tears in my eyes and a choking sensation in my throat.”

Benjamin Brown French also went to the White House on the afternoon of Sunday, April 16, to confirm that all was going well in the East Room with the preparations for Lincoln’s April 19 funeral. Then he went upstairs to view the embalmed corpse: “I saw the remains of the President, which are growing more and more natural…but for the bloodshot appearance of the cheek directly under the right eye, the face would look perfectly natural.”

After spending an hour at the Executive Mansion, French visited Secretary of State Seward, who gave him a firsthand account of the savage knife attack he was lucky to have survived. French left Seward’s home with Senator Solomon Foot of Vermont, and they went back to the White House. French wanted to see the corpse again: “We stood together at the side of the form of him whom, in life, we both loved so well.”

Orville Hickman Browning came to the White House to view the corpse at least twice before the funeral, first for the autopsy on Saturday the fifteenth, and then on Monday the seventeenth. Browning had watched the surgeons saw off the top of his friend’s cranium and remove his brain. It was bloody, ugly work. Two days later, Browning observed how the embalmer’s artistry had improved Lincoln’s appearance. The president, he wrote, “was looking as natural as life, and if in a quiet sleep. We all think the body should be taken to Springfield for internment, but Mrs. Lincoln is vehemently opposed to it, and wishes it to go to Chicago.”

Except for these visitors and a few others—and the ever-present military honor guards standing in motionless vigil—the corpse was alone. Lincoln had finally won the solitude he craved during his presidency, when patronage seekers, influence peddlers, and lobbyists camped out near his door and harassed him so thoroughly that he felt under perpetual siege in his own office. Lincoln fought back by having a White House carpenter build a partition in the anteroom to conceal him from public view as he crossed between his second-floor office and his living quarters.

The construction of this private passage amused the great Civil War journalist George Alfred Townsend.

It tells a long story of duns and loiterers, contract-hunters and seekers for commissions, garrulous parents on paltry errands, toadies without measure and talkers without conscience. They pressed upon him through the great door opposite his window, and hat in hand, came courtsying to his chair, with an obsequious “Mr. President!” If he dared, though the chief magistrate and commander of the army and navy, to go out the great door, these vampires leaped upon him with their Babylonian pleas, and barred his walk to his hearthside. He could not insult them since it was not in his nature, and perhaps

many of them had really urgent errands. So he called up the carpenter and ordered a strategic route cut from his office to his hearth, and perhaps told of it after with much merriment.

Now that traffic had ceased, and for the first time in four years, the human jackals did not skulk about the second floor, staking out his office. Once, when sick with smallpox, Lincoln had joked, “Now I have something I can give to everyone!”

The only sounds now were ones Lincoln would have recalled from childhood—wood saws cutting, hammers pounding nails, carpenters at work. Workmen in the East Room were building the catafalque upon which his elaborate coffin, not yet finished, would rest during the public viewing and state funeral. These sounds were the familiar music of his youth, made by his carpenter father, Thomas. It was the echo of his own labor too, when he had a rail-splitting axe placed in his hands at the age of nine. But the noise frightened Mary Lincoln; the hammer strikes reminded her of gunshots.

Strangely, not once during the days and nights that the president’s corpse lay in seclusion at the White House did Mary make a private visit to her husband. Her last nightmare vision of him, bleeding, gasping, mortally wounded, dying in the overcrowded, stuffy little back bedroom of the Petersen house, had traumatized her and she could not bear to walk the short distance from her bedchamber to the Guest Room and look upon his face now. History does not record whether her son Robert defied her morbid imprisonment of Tad in her frightening mourning chamber and whether he took his little brother to the Guest Room to view their father, just as, three years before, Abraham had carried Tad from his bed to view his brother Willie in death.