Blood Work (20 page)

Authors: Holly Tucker

As news of Mauroy's death spread, these and other

anti-transfuseurs

reported the news gleefully in their correspondence. In a chorus of “I told you sos” they accused Denis of being too quick to take credit for his success. Accusations against the transfusionist were now also swirling openly among the highest-ranking members of the king's court. On February 15, 1668, Louis XIV's secretary, Henri Justel, was finishing a lengthy letter to Oldenburg with a summary of the latest French gossip. He had just reached for the pounce powder to dry the ink when he was told of Mauroy's death. He was sure that Oldenburg would want to know right away. The courier was waiting to speed the letter across the Channel, so Justel reached for a small slip of paper and appended the news to his letter. “After my letter was written,” Justel wrote briskly, “I learned that the madman who had received the blood transfusion is dead. So Monsieur Denis boasted inopportunely of his cure. He should have waited.”

6

Ten days later Justel further reported to Oldenburg that transfusion was “being cried down.”

7

“Their mischance,” Justel explained smugly, “will discredit transfusion and no one will dare to try it in the future on men.”

8

THE AFFAIR OF THE POISONS

D

enis had always delighted in stirring up controversy, yet the transfusionist knew better than to inflame his detractors, who were hard at work concocting a case against him. In the months that followed Mauroy's death Denis had little choice but to remain silent. Without a corpse, he knew that he could not offer a definitive explanation for the man's demise. Still, Denis stood firm in his conviction that transfusion had not killed Mauroy. In fact he became more convinced than ever that his patient had been the victim of foul play.

Hope came two months later, in the form of Perrine Mauroy. Standing on the doorstep of Denis' home on the Left Bank, Perrine looked up at the transfusionist with contrition. She claimed that several men, physicians all, had circled her home in the days following her husband's death. They waved large amounts of money and “did extremely solicit her to bear false witness against Denis” they had even spoken to all her neighbors so that they might persuade her to bear false witness in the courts. The repentant Perrine told Denis that she had refused, “knowing her

obligations to [Denis] for having relieved her husband freely.” Denis expressed his own gratitude to Perrine for her excellent judgment. Still, he suspected that he had not yet heard everything that she had come to say.

1

He was right.

Perrine described with much pathos her plight as a penniless widow. Turning on as much charm as she could, she told Denis that she had done everything she could to resist the money that they had offered her. Perhaps he might be able to help her? She had been inside Montmor's sprawling compound and knew that Denis benefited from the generosity of his patron. Certainly he and

Montmor le Riche

would see fit to help her out so that she would not have to accept the bribes of others. Unmoved, Denis snapped at Perrine. He told her angrily that “those Physicians and herself stood more in need of the transfusion than ever her husband had done,” and that he did not care for threats.

2

Perrine left in a huff.

The widow's story of outside involvement, by other physicians no less, made it clear to Denis that a plot was brewing against him. Something very similar had happened to Nicolas Fouquet a few years earlier. The superintendent of finances had dared to put on an unforgettable display of wealth and hospitality during a visit by Louis XIV to his estate at Vaux-le-Vicomte. He was not punished immediately for his transgressions. Instead the king and his soon-to-be prime minister, Colbert, coordinated a surprise arrest a full month after the fateful party. Now Fouquet was wasting away in solitary confinement in the dungeons of Vincennes.

Denis knew his ambitions had led him directly into the path of the sun: Louis XIV, the Sun King himself. The transfusionist had gone directly against the will of the king's Academy of Sciences as well as the major players at the conservative Paris Faculty of Medicine. It is not clear whether Denis' next actions were intended to preempt a strike that he knew was coming or

whether it was a last show of his characteristic arrogance. Perhaps it was both. What is certain, however, is that Denis still believed unequivocally in the potential of blood transfusion. He resolved that he would get to the bottom of things and restore not only his good name but also the procedure on which he had staked his reputation.

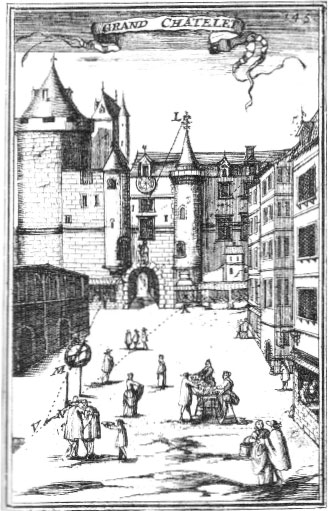

Not long after Perrine's unexpected visit to his home, Denis made a visit to the fortressed Grand Châtelet, which stood menacingly on the Right Bank of the city. From the fourteenth century to its demolition in the nineteenth century, the Grand Châtelet was home to the main criminal and civil courts for the city of Paris and its surrounding villages. The massive building cast an eerie shadow over the river below. And behind its six-foot-thick walls the Châtelet teemed with activity as hundreds of lawyers, judges, notaries, plaintiffs, and defendants filled its many courtrooms daily.

Prime Minister Colbert had just recently brought the courts and the police system together under the same roof by reserving a special set of rooms in the overcrowded Châtelet for Nicolas de la Reynie, the newly appointed police chief of Paris. In short order Reynie put his mark on Paris as he tried to free the city from its infamous reputation as the crime and murder capital of Europe. Before Reynie's appointment, few people had been safe from the random acts of violence that defined daily life in Parisânot even one of the highest-ranking judges at Châtelet, the “Criminal Lieutenant” himself. In August 1665 the Honorable Jacques Tardieu and his wife were murdered in broad daylight and in their own home, victims of an armed robbery. Colbert had appointed Reynie because he had seen enough, and he gave his new police chief the exceptionally broad powers needed to restore order to the violent city.

Reynie's presence in the castle-like compound only intensified

the Grand Châtelet's chilling reputation. Châtelet was legendary for its horrific conditions and deadly spectacles. The sprawling complex was infested with legions of rats that migrated from nearby slaughterhouses. The Châtelet also served as the city's main morgue, where the bodies of less fortunate prisoners were

collected along with the many others that were regularly discovered in the streets of Paris or found floating in the Seine.

3

The Châtelet's stench was recognizable to every Parisian and hovered permanently in the air throughout the streets around the fortress.

FIGURE 21:

The notorious Grand Châtelet was both a major prison and the seat of the Paris courts in early France. It sat on the Right Bank of the Seine, directly across the river from the Conciergerie and Parliament. It was demolished in the early nineteenth century.

In early Europe justice and death often went hand in hand. Many prisoners were crammed into windowless cells in the Grand Châtelet's largest turret. Others were left in

cachots

or

oubliettes

(from the French

cacher

, “to hide,” and

oublier

, “to forget”) in dungeons dug nearly five stories underground. Defendants in criminal cases who entered the Châtelet's courtrooms worried that they, too, could be sentenced to one of these prison cellsâor perhaps lowered into the “pit.” (The most notorious criminals were sent into what was likely a well-like shaft by means of a bucket and pulley. Unable to sit or lie down, they stood with water around their feet until they collapsed and diedâusually after about two weeks.)

4

Denis set out for the fortress intent on clearing his name of the accusations of ineptitude or, worse, murder that were now being made against him. In self-defense, he lodged a formal complaint against Mauroy's widow and her still unnamed accomplices. As his carriage approached the main entrance of the Châtelet, the transfusionist was confident that the police chief's commissioners and the judges there would be as appalled as he was by the widow's story of bribery and extortion. The coachman tried with difficulty to navigate the stream of bedraggled Parisians who elbowed one another for their place in line to meet with one of the police commissioners in order to report the transgressions of other city dwellers. When Denis stepped out of his carriage, the guard at the gate noted the physician's fine clothes and assured manner. In a matter of moments he was escorted to the Châtelet's main courtyard, up a set of massive stone stairs, and into a private room off the main corridor of the police headquarters.

In this room and away from prying eyes, commissioners met with “persons of quality” who either brought complaints against others, or who were questioned quietly about complaints brought against them.

5

Trying hard to keep his outrage in check, Denis told Commissioner Le Cerf his story. He described his medical experiments and explained with pride how he had transfused Mauroy successfully on two occasions, along with several others who were very much still alive to vouch for his skills. Denis crafted the case for his innocence and worked diligently to turn the commissioner's suspicions toward the bribing and conniving widow and those who had helped hasten the death of Antoine Mauroy. Surely, Denis argued, if the king was interested in keeping the streets clean of evildoers, the commissioner had little choice but to investigate the case. Finding sufficient grounds for concern, La Cerf forwarded the case to the Criminal Lieutenant, the Honorable Jacques Defita, for a full hearing.

6

Courtrooms at the Châtelet were like theaters. A judge dressed in a flowing black gown and a perfectly coiffed wig sat high above the crowds on a narrow, oval-shaped proscenium. Lawyers for each side as well as a recording notary clustered around a table below and looked out at the men and women who had been brought in to tell their tales. On April 17, 1668, five peopleâDenis, Emmerez, Perrine Mauroy, and two of her neighborsâstood nervously in front of the table as they strained their necks to have a look at Judge Defita. Perrine and her neighbors seemed disheveled and out of place compared with the black-velvet-gowned lawyers who stood before them. Denis, on the other hand, wore an elaborately stitched waistcoat and expensive knee breeches and looked as if he belonged fully to the French court and its nobility. A balustrade behind them separated the space of testimony and judgment from a crowd of gawking spectators, agog with excitement and curiosity.

Judge Defita solemnly nodded to the two lawyers representing each side of the case. Sitting in the high-backed chair on the stage, he asked no questions. As was the tradition, he left the talking to his assistant, André Lefèvre d'Ormesson, who sat at his side. Barely twenty-three years old, Ormesson was still green. Like most young lawyers at the Châtelet, he came from an illustrious legal family and had been appointed to the post as a way to gain experience in the legal ranks before he took a position more worthy of his name. Denis could not have been more pleased that an Ormesson had been assigned to his case. André's legendary father, Olivier Lefèvre d'Ormesson, had risked his entire career to ensure a fair trial for Nicolas Fouquet. In the months following Fouquet's catastrophic party at Vaux-le-Vicomte, Fouquet's fateâand his very lifeâhad been at the mercy of the courts. Serving as judge at the trial, the elder Ormesson refused to rubber-stamp the monarchy's case against Louis' former superintendent of finances. Colbert had expected the courts to move swiftly and deliver a death sentence. Instead Ormesson spent five long days in public deliberation and exposed the many irregularities he found in the case. Ormesson had the most serious charges dropped, effectively protecting Fouquet from the gallows. While Fouquet did receive a life sentence, Louis XIV and Colbert were nevertheless displeased. Not long after the ruling Ormesson “retired” from the court.

The younger Ormesson was well aware that the Denis case had many similarities to his father's famous trial. The Fouquet hearing had been a test of France's long-standing legal system in the wake of the new king's efforts to consolidate his power. Ormesson no doubt believed, like his father, that Denisâand transfusion more generallyâdeserved a fair trial. But it would have been foolhardy to overlook the political stakes of the case. Led by Guillaume Lamy and Claude Perrault, the University of

Paris medical school had made no secret of its outrage that Denis had been performing experiments without its express approval. The faculty had also made clear, through formal and informal routes, transfusion was to be stopped, quickly and for good. And if it took the death of a pitiful homeless man to make that happen, so be it.

When the members of the court had taken their places, Ormesson called his first witness. The room hushed as Denis approached the lawyer's table. He was asked to relate from memory the events leading up to Mauroy's death. Looking both Defita and Ormesson directly in the eye, the transfusionist described how he and Emmerez had transfused Mauroy on two occasions, each time with great success. In the two months that followed, he had carefully monitored the man's health and found him to be “in his good senses and in good health.”

7

Denis described at length the difficulty that he and Emmerez had when they attempted the procedure for the third time. They had barely begun to bleed their patient in preparation for the procedure when the man began to have repetitive seizures, and as much as he had intended to perform the procedure, the man's condition prevented it. To no one's surprise Emmerez confirmed all of Denis' statements.

Ormesson then turned to the widow Mauroy. Existing records do not describe her demeanor, but we may imagine that she was terrified. A simple villager unfamiliar with the tight-knit social world of the Parisian upper classes, Perrine had undertaken an unthinkable odyssey. Just months earlier she had found herself in the Montmor estate which, despite the nobleman's change of fortune among scientists, remained one of the city's most opulent addresses. And now here she was in the capital's legendary home of justiceâand death. Ormesson pushed the trembling widow to provide details about daily life with her husband in the short time between the first round of transfusions and his death. Per

rine begged the lawyer to believe that she loved her husband. She had always taken great pains to respond to his every need. She fed him, she clothed him, and she prepared his eggs and broths.