Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain (25 page)

Read Blood on the Tracks: A History of Railway Crime in Britain Online

Authors: David Brandon,Alan Brooke

Over a week or two he made repeated visits to the clerk, passing the time of day over a mug of tea until the fatal evening when, although the office had closed as we have heard, the luckless Dean was catching up with the backlog. Fatally he admitted Alcott who, after a few minutes, launched a savage attack. Dean put up a good, but not good enough, fight. Alcott was sentenced to death for what was described by the judge as a ‘cold-blooded murder’. Dean had been a married man with a young daughter.

It turned out that Alcott had been in trouble with the authorities before. In 1949 he was in the Coldstream Guards serving in Germany and had been sentenced to death for the murder of a German civilian but he had evaded execution on some technicality. His appointment with the famed public hangman Albert Pierrepoint was at Wandsworth Prison on Friday 2 June 1953 and was brief and one-sided.

A recent view of Ash Vale station, hardly an impressive building. It has, however, to be better than a bus shelter.

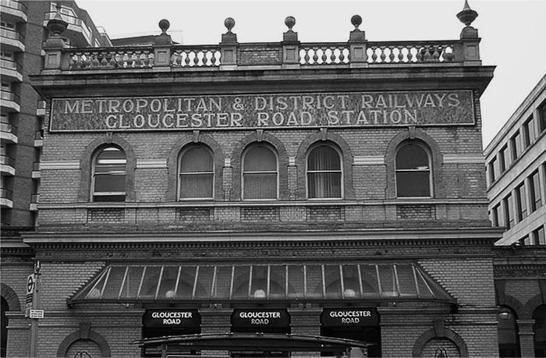

What happened at Gloucester Road Tube?

It is probably true to say that there have been remarkably few murders on the London Underground given the massive passenger usage of the system over what is now almost a century and a half since the first trains ran between Paddington and Farringdon. One twentieth-century murder has never been solved.

It occurred on 24 May 1957 at Gloucester Road on the deep-level Piccadilly Line part of the station. An aristocratic lady of Polish extraction, Teresa Lubienska, was seen by witnesses leaving a tube train but unfortunately before the day of CCTV; no one saw what happened next. She was evidently attacked and apparently stabbed many times by an unknown assailant who is thought to have escaped via the emergency staircase. Her body was found soon after she had died but no clue has ever been established as to the motive for the murder or to the identity of the murderer.

Frontage of the present-day Gloucester Road underground station. We should be pleased that some thoughtful restoration work has been carried out on this building.

Slam-door electric multiple-units of the type once so familiar in London’s southern suburbs. The picture is taken at Addiscombe which no longer sees ‘heavy-rail’ trains but is served by the very successful Croydon Tramlink.

More Recent Crimes

We chose not to enter into detail about the more recent serious crimes to take place on Britain’s railways, but crime has continued. In the 1980s, a number of young women were sexually assaulted, raped and sometimes murdered on or around railway property in the Greater London area. The reports of these attacks made many women reluctant to travel but the life of the metropolis had to go on and women of necessity continued to travel by themselves. The dual perpetrators of these crimes were apprehended and punished.

Another crime of the 1980s involved a woman travelling in the compartment of a slam-door electric multiple-unit. On the train’s arrival at its destination, the woman’s body was discovered having suffered multiple stab wounds. This case remains open.

The railway has also been used as a secondary tool in murder. It has been known for murderers, having killed their victims, to then place the body on a railway track in the hope that a passing train would make the death appear accidental.

I

n this chapter we take a brief look at some aspects of crime associated with the railways which are not dealt with elsewhere in the book.

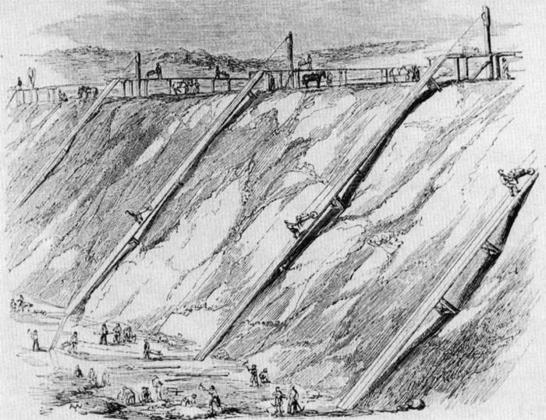

A case could be made for saying that the navvies were the unsung heroes of Britain’s railway revolution. They laboured in huge numbers doing the most difficult and dangerous work when over 20,000 route miles of railways were being built in the nineteenth century. It was the navvies who hewed away at solid rock making cuttings and tunnels, and it was their skilled physical efforts that enabled the building of thousands of embankments, bridges and viaducts.

The names of the big contractors such as Peto and Brassey have lived on, but those of the navvies – many of them who died or were maimed while doing this heroic work – have largely been forgotten. That the role of the navvies has to some extent become better appreciated owes much to the pioneering work of Terry Coleman, whose book

The Railway Navvies

was first published in 1965. It was aptly subtitled ‘The history of the men who made the railways’. Other, later examples of this kind of history from below have expanded on and amplified what Coleman wrote.

These writers show that the blame for many of the accidents in which men died or were injured can be laid at the feet of those contractors who placed profit before the safety and welfare of their workers. They also demonstrate how the men were defrauded, often by subcontractors who frequently used the truck system to pay the men a substantial part of their wages in the form of tokens which were only redeemable at the subcontractors own shops. There they ripped the navvies off with high prices and poor-quality goods

which were often underweight. Few contractors ever faced legal proceedings. There were some contractors, however, who treated their men decently.

The navvies, it has to be said, were no saints. They often came like an invading army and a large force of such men was bound to upset the relative tranquillity of remote rural settlements that were close to the path of such lines as the Settle & Carlisle and the Carlisle to Edinburgh ‘Waverley Route’. The navvies frequently boasted of their drinking, eating and fighting prowess and were shunned and feared by many for their apparent godlessness. They gambled, they poached, they swore, they blasphemed and they swaggered around in their distinctive clothes. They cared not one toss for the mores of middle-class Victorian society while they looked down loftily on the ordinary labourers who did the routine jobs on the construction sites and were not part of the elite. The navvies even had women with them in their encampments who were not their wives. This scandalised respectable Victorian society!

Many of the navvies were of Irish and Scottish origin. They had a marked antipathy to the English navvies, a feeling which was heartily reciprocated. When a reason could be found, and they did not have to look hard, then the Irish fought the Scots or the English, or two of the ethnic groups would combine to fight the third. Such groupings could change overnight. Inevitably the presence of large numbers of rough, tough itinerant alpha males led to trouble – with each other and with the local police. The latter were often hopelessly outnumbered and overawed by the presence of the navvies.

The disputes, which sometimes evolved into riots, were often about concrete issues facing the navvies in their everyday work. These might involve wage rates or complaints about the truck or ‘tommy-shops’ and in these cases ethnic considerations usually took second place to workers’ solidarity. Trouble was most frequent when the men were paid, which was sometimes only monthly and often in a pub – a mutually advantageous arrangement made between contractor and publican.

Temporarily flush with money, the navvies would embark on a monster drinking orgy which on at least one occasion ended when the pub ran out of beer and the navvies, who by this time were fighting mad, showed their disgust by literally pulling the building down. On occasions the railway contractors used navvies as soldiers in battles with landowners and their retainers, or even other contractors, a kind of strange reprise of the old days of feudalism. Examples include the ‘Battles’ of Saxby on the Rutland and Leicestershire border, Mickleton Tunnel in Worcestershire and Clifton Junction, north of Manchester.

It would be wrong to conclude that the navvies were a wholly lawless and nihilistic group of men. Most of their working hours and their leisure activities were, of course, carried out entirely unexceptionally. The vast majority of navvies were law-abiding for most of the time. As always from the point of view of the media the only good news was bad news, and the books written

about them have made much of the activities that came to the attention of the authorities at the time. This has inevitably coloured popular perceptions of the navvies but the reality is that, collectively, they made an enormous contribution to the creation of Britain’s railway system and therefore to the revolutionary impact that the railways had on the economy and on society.

Barrow-runs in use during the building of a deep cutting, probably on the London & Birmingham Railway in the late 1830s. A horse at the top pulled the wooden barrow up the wooden ramp, steered by the navvy, an extremely hazardous operation especially when the ramp was slippery with mud.

Although the names of the individuals concerned have largely been forgotten, it is pleasant to record that at Otley in West Yorkshire and close to the parish church of All Saints there is a monument to twenty-three railway navvies. They lost their lives in the building of Bramhope Tunnel on what became known as the Leeds Northern Railway between Leeds and Northallerton. The line was opened throughout in 1849 and the tunnel was then the third longest in Britain. The monument, towards the cost of which the contractor made a substantial contribution, consists of a miniature railway tunnel with two splendidly castellated portals. Its maximum height is 6ft. It is inscribed with a number of biblical quotations but not with the names of any of those who had died.