Blood & Milk

Authors: N.R. Walker

BLOOD & MILK

By

N.R. WALKER

Copyright:

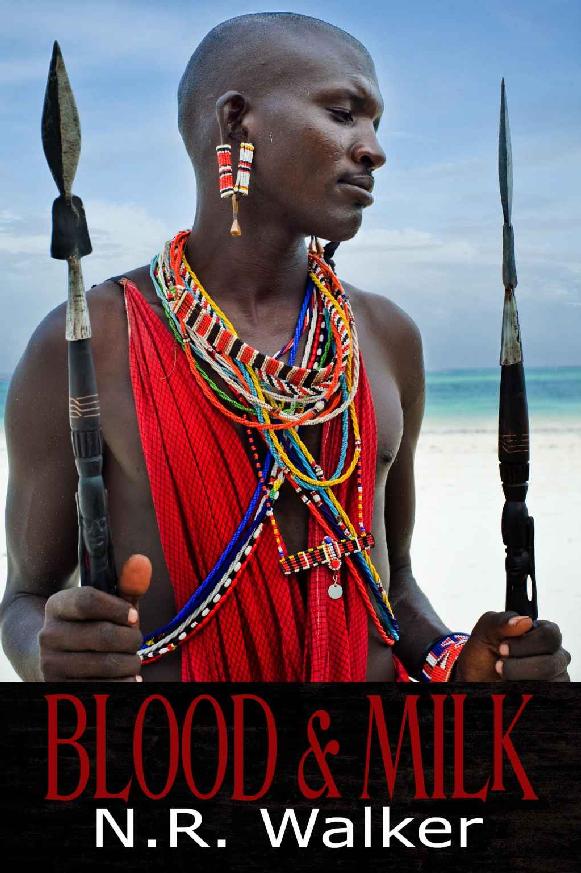

Cover Artist: Sara York

Editor: Labyrinth Bound Edits

Proofreaders: Jay Northcote, Cristina Manole

Blood & Milk © 2016 N.R. Walker

Publisher: BlueHeart Press

All Rights Reserved:

This literary work may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic or photographic reproduction, in whole or in part, without express written permission.

This is a work of fiction, and any resemblance to persons, living or dead, or business establishments, events or locales is coincidental.

The Licensed Art Material is being used for illustrative purposes only.

All Rights Are Reserved. No part of this may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Warning:

Intended for an 18+ audience only. This book contains material that maybe offensive to some and is intended for a mature, adult audience. It contains graphic language, explicit sexual content, and adult situations.

The author uses Australian English spelling and grammar.

Trigger warnings

: Homophobic violence. Reader discretion advised.

The author acknowledges the trademarked status and trademark owners of the following wordmarks mentioned in this work of fiction:

Morris Minor: Morris Motors Ltd

Google: Google, Inc.

Jumanji: 1995, Tristar Pictures

Lion King: Walt Disney Pictures

Land Rover: The Rover Company Ltd

Colgate: Colgate-Palmolive Co.

Styrofoam: Dow Chemical Co.

Coke: The Coca Cola Company

Alé: Ah-leh

Damu: Dah-mu

Nkorisa: En-kor-issa

Kijani: Key-yar-nee

Kasisi: Kah-see-see

Mposi: Em-poss-ee

Common terms used throughout

:

Manyatta/Kraal: Maasai village, surrounded by an acacia thorn fence.

Shuka: Traditional red shawl worn by the Maasai

Rungu: Wooden club, used/thrown as weapon

Diviner: Tribal witchdoctor

Uji: Thin, milk-like consistency drink made from water and maize.

Ugali: Water and maize mix with the consistency of mashed potatoes.

At the date of publication, June 2016, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, or ILGA, lists 73 countries with criminal laws against sexual activity by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex people, punishable by imprisonment, torture, or death. 33 of these countries are in Africa, Tanzania being one of them.

To my African friends who read my books, I am truly honoured, and incredibly humbled. Your strength encourages me, and to know my words give you hope and happiness is a gift that will stay with me forever.

Nawatakiya amani na upendo.

The

African Human Rights Coalition

does some amazing work for LGBTIQ people, and donations are always welcome.

To Santa Aziz,

For helping me with true Maasai ways, diet, language and culture, and for giving me the courage to publish this story. But especially for reminding me why words are important.

This book is for you.

A Very Special Mention:

To the many pre-readers and beta-readers who helped and guided, suggested and corrected. You made this book better, and I thank you.

It was twelve months on. A full year had passed, yet my world had stopped completely. The men who stole my life were charged and would serve time for their crime. No one called it a hate crime, but that’s what it was. If I was expecting some sort of finality to come with the court findings, I didn’t get it.

I was still hollow. I was still numb to the world, and I was still alone.

I was also awarded damages, civilian victim and medical.

A nice healthy sum that meant I could pay off my debts after not working for twelve months, and more. Though no amount of money would make this right. No amount of money would bring him back.

My mother came along for the final hearing, though I could only guess why. I had barely spoken two words to her in the last year. Maybe she came so she could vie for the sympathy card with her friends. Or maybe she thought she could have one last twist of the knife…

“Now it’s all over,” she said, nodding her head like her words were wise and final. “You can put all this homosexual nonsense behind you.”

I looked at my mother and smiled. I fucking smiled. I raged inside with a fury to burn the world, and maybe she saw something in my eyes―maybe it was a ferocity she’d never seen before, maybe it was madness―and my words were whisper quiet.

“You are a despicable, bitter human being, and you are a disgrace to mothers everywhere. So, when you go to your church group, instead of praying for my soul, you should be praying for yours. You have only hate and judgement in your heart, and you are doomed to an eternity in hell.” I leaned in close and sneered at her. “And I hope you fucking burn.” I stood up and stared down at her. She was pale and shocked, and I did not care. “If you think my words are cold and cruel,” I added, “I want you to know I learned them from you.”

I walked away, for the final time. I knew I’d never see her again, and I had made my peace with that.

I didn’t care for the money. I didn’t care for anything. I longed for sleep, because in my dreams, I saw him. And that night, almost one year to the day since he was gone, in our too-big bed, in our too-quiet flat, in my too-alone life, I dreamed of Jarrod.

He sat on our bed and grinned. I longed to hear his voice, just once. It’d been a year and I craved the sound of his voice, his touch. But when I reached out for him, even in my dream, as in my waking nightmares, he was gone. I sat up in our bed, reaching out for nothing but air. He was gone, really gone.

But in this dream, on the bed where he’d sat, was a plane ticket. Mr Heath Crowley, it said. One way ticket to Tanzania.

The flight from Sydney, Australia, to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, was long, though I didn’t remember much of it. Much like the last twelve months of my life, zoning out and staring into space for undetermined lengths of time made my days bearable. My connecting flight to Arusha, with a fly-by view of Mount Kilimanjaro, was much less pleasant.

The Australian couple I had the misfortune of sitting next to were off on some great safari, glamour camping trip, according to their never ending attempt at conversation.

“You have odd coloured eyes,” the woman said bluntly, like I might not have known. She stared into each of my eyes like she was looking to see if she could find a way to fix them. “One’s brown, one’s a greeny-hazel colour.”

“Ah, yes. I know. Heterochromia. Don’t worry, it’s not contagious.”

She snorted rudely. “My sister had a dog with odd eyes.”

I repressed a sigh. Funnily enough, most people made a similar comment when they first met me. You’d think someone having different coloured eyes was the most absurd thing they’d ever seen, but, to me, it was as obtuse as me telling her she had blonde hair like it was some kind of disease. She clearly didn’t pick up on my want for silence.

“Are you travelling alone?”

“Yes.”

“In an organised tour?”

“No.”

“Are you meeting someone there?”

“Yeah.”

She visibly relaxed. “Oh, that’s good. I hear it can be very dangerous if you’re not in a group tour.”

I didn’t explain that I’d made one phone call and, for a nominal fee and something akin to a breath of hope, would be meeting a man whose name I couldn’t remember, and he would be taking me to a remote tribe of Maasai who had no clue I was coming.

Why? Because I’d dreamed of this.

Not dreamed of, as in a bucket-list aspiration kind of dream. But literally dreamed it. I’d had many instances, where my dreams foretold events that would inevitably shape my life. Not like normal dreams. These premonition-type dreams were the ones that woke me with a piercing weight on my breastbone. I would wake up in a cold sweat with vivid images screaming through my mind. Then, in the near future―a day, a week, a month―the dream would happen in my waking life. I couldn’t explain it, and only a few people ever knew about my

talent.

Or curse.

I had a dream that told me I must go to Tanzania and that I would live with the Maasai. So, with absolutely nothing left to keep me tethered to my life in Sydney, I made a phone call, booked a ticket, and boarded a plane.

The woman beside me was still prattling on, her ignorance and naivety keeping company with her good intentions. “You read the travel warnings, yes? I’ve heard all the horror stories of people who come to these far-off countries by themselves. You must be so careful, or you might find yourself not coming back at all.”

“It wouldn’t much matter if I didn’t,” I mumbled. “Waking up in a bathtub of ice with one less kidney isn’t so bad. I’ve lived through worse.”

She blinked back her surprise and stopped talking to me after that. I smiled internally, put on the headphones, and closed my eyes, grateful for the peace and solitude.

When we’d landed, and even as we made it through the concourse and were herded out to the blistering heat of East Africa, I still kept to myself. The majority of other people were ushered onto tourist buses to the right. I went to the left, armed with no more than the backpack I brought with me. The sun was blinding, so I kept my head down and almost missed the guy waiting for me.

“Are you Mister Cowley?”

I looked up to find a man, a few inches taller than my five ten. He had short hair, nubbed at his scalp, dark brown skin, and a smile that showed almost every single one of his teeth.

“Crowley,” I corrected, not that it probably mattered. No one else here knew I was coming, except the one person I’d given my name and flight details to, the man who would drive me to the Maasai. “And you are?” I was expecting an Eric, I thankfully remembered, but I wasn’t naïve enough to give a stranger the name of the person I was waiting for.

“I am Eric. I wait here for you.” His English was broken, but he nodded enthusiastically. “You want to go to the Isikirari people. I take you.”

I offered him my hand, which he shook with just as much enthusiasm as he smiled. “Heath Crowley.”

“You come with me,” he said. His smile never faltered, and without one iota of concern for my safety, I followed him. He stopped at a car―if it could be described as that―and I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

The car itself was an early 60s model Morris Minor, held together by rust and goodwill. But inside the car, piled into the backseat, were two other men… and three goats.

“Um.” I wasn’t sure what the hell to do.

“You get in front,” Eric said. His grin was somewhat reassuring.

I did as he asked and climbed in. The smell inside the car was an unholy mix of sweat and piss―human or goat, I couldn’t tell. And for the next hour, Eric drove west. The scenery was beautiful, just like I’d imagined it to be. Arusha was green with Mount Meru as a backdrop to the north, and the countryside as we drove was mostly farmland.

I had no idea where he was taking me, and it occurred to me that I didn’t really care. We went through a few smaller towns, and I tried to take in as much as I could. I felt so removed from the fact that I was actually heading toward the Serengeti. Well, I hoped I was. Eric asked me a few questions and pointed out a few landmarks, and the two men who both eyed me warily in the back with the bleating, stinking goats, never said a word.

Eventually we came to the large gateway to the World Heritage’s Ngorongoro Conservation Area. It was a name I remembered from the maps I’d studied, so I knew Eric had at least taken me in the right direction. There were a few mudbrick buildings and a flow of safari buses that surprised me but then we passed a huge, westernised looking tourist safari hotel and I understood why.

This really was the gateway to the Serengeti.

Then, at a turn off in what looked like the middle of flat grassland, Eric brought the car to a stop. I was almost hoping we’d lose the two silent guys and their goats but that wasn’t what happened at all. Eric stopped in the middle of the road and the two guys got out from the backseat taking their goats with them. Then Eric held out his hand. “Pay now.”

Right. I paid him the eighty-thousand Tanzanian shillings I’d agreed to, which equated to about fifty Australian dollars. I folded up the rest of my money and slid some into my backpack, some into my sock, and some into my shirt pocket. I’d travelled enough to know to separate my money. “Where to now?” I asked.

“You go with them,” Eric said, pointing in the direction the two men had gone. They were already a hundred yards ahead and were, by all accounts, walking into the middle of nowhere. “They take you.”

“The two men with the goats?”

“Yes, yes,” he said, still with the grin. “Hurry, hurry.”

Shit.

I grabbed my backpack and scrambled out of the car. I waved my thanks as I ran after the two men. There was no turning back now. Eric was already driving away and I had to run to catch up to my guides.

“I’m coming with you, yes?” I asked them.

One man, the shorter of the two, turned his head in acknowledgment, though he never spoke. Actually, they never even looked directly at me, but they never stopped or said no, they never hunted me away, so I assumed it was okay to follow them. I stayed a few metres behind, and we walked. And walked, and then we walked some more.

I had no clue where we were going, or how long we would be walking for. From the direction of the setting sun, I deduced we were heading west. The sun was hotter and brighter than I thought possible, probably because we were walking directly into it. Though I was surprised by how green everything was; the grasses were long and danced in the breeze. I’d always imagined Africa to be arid, much like central Australia, but this was very fertile land.

Still walking, I sipped at my bottled water sparingly. I resisted the urge to complain or even speak. The two men remained silent, but from what I could ascertain, they were happy in their camaraderie, and as we continued to walk, I wondered if they were indeed brothers. They looked alike: both tall and lean, thin even, with dark skin and short, nubbed hair. But it wasn’t even their looks. They walked the same: long, confident strides, moving purposefully, yet there was a stillness about them.

And we walked.

I took in the scenery and kept reminding myself that I was walking the Serengeti. The landscape was beautiful. Remote and so removed from anything I’d seen in regional Australia. This was a foreign vastness, a different kind of isolation, than anything I’d experienced back home. The trees that spotted the scenery were no longer eucalypt, as they were back home, but were flat-top African acacias, which were so typical in photos of Africa. A herd of some kind of bison were off in the distance, and I tried hard not to wonder if there were lions anywhere close by.

The two men strode easily over the rocks and tussock grasses. And for the hours I walked behind them, I studied them as well. Their sandals were made from old tyres. Crude and elementary, but functional. Their clothes were threadbare and dirty: not a judgement, merely an observation. They had beaded loops instead of earlobes and I could see necklaces hidden by their shirts.

Were they Maasai or just villagers taking me to the Maasai?

I had no idea.

I merely walked behind them, thankful the setting sun had taken the baking heat with it. But the cool change brought with it another element I’d not expected. Darkness.

The men in front of me were obviously familiar with their environment, and as evening became night, their silence as they walked became eerie. Thankfully the noisy goats kept me on track and just when I couldn’t see my own hand in front of my face, and just when I was about to ask the men how much further, a faint orange light came into view.

When I’d booked my ticket to come here, I had done some research. Well, all that Google and travel forums would allow. I knew the village itself was called a

manyatta

or

kraal

, with a wall built of thorns to surround and protect the people and livestock within.

In an otherwise all-surrounding blackness, the flickering of orange I didn’t realise until we were right up on it, was the fire I was seeing near the thorn walls of the kraal. The two men ahead of me stopped and faced me. “Stop,” one of them said.

The other man disappeared through the narrow gateway with the goats, and I stood there under the watchful eye of the other guy. Just a short moment later, I heard voices, then a long line of people filed out of the manyatta. They formed a half-circle around me; my back to the wall. And within half a minute, I was surrounded by dozens of people. Maasai people, tall, imposing, and intimidating. I could barely make them out―the night was too dark―but there was an air of concern and danger to them.

I didn’t need to speak Maa to know they were alarmed at my presence. Outraged even. A tall man, well over six foot, confronted me, draped in red cloth and wielding a long spear, he spoke in my face. His eyes and teeth looked yellow in the lack of light; his disposition was formidable. “What you do here?”

Quickly recognising he was a respected tribal man, I kept my head down, knowing my place here was well beneath his. “I mean no harm,” I said, surprised by the strength of my own voice. “I have come to live with your people. If you would have me. Please. I want to learn your ways.”

Conversation swept through the village, murmurs and rumbles of unease. The man before me raised his hand and a silence hushed over the people. He gripped my chin and forced my face upwards so he could see my face.

His eyes went wide, and he yelled something I couldn’t comprehend. Was it a name? Was he calling for someone else?

I should have been afraid. I should have run away. But instead I stood there, without any thought of self-preservation, under the scrutiny of a man who might possibly kill me.

Then another man, much older and smaller, wearing a headdress of some sort―I couldn’t quite make it out in the darkness―draped in red, with beaded necklaces, appeared in front of me. The crowd moved for him, a clear mark of respect. He came to stand in front of me, and when he saw my different coloured eyes, he let out a long gasp.

He spoke words in Maa I could not begin to understand―a quiet timbre to his voice, but with strength as well. From his reaction, I could see he was excited and even amazed. Waves of disbelief and murmurs spread through the people encircled around us. Whatever he called me, the words I didn’t understand, must have meant something to them.

The small village elder smiled at me by the firelight. Then he spoke in broken English. “Broken man. Incomplete, but he brave. No fear.” I wasn’t sure what to make of that. But then he said, “He dreams.”

Well, I understood that. “Yes. My dreams told me to come here.”

The first man, the angry warrior guy, didn’t like that at all. He spoke harshly to the elder, stomping his spear to the ground. I made no sense of his words, only his demeanour. He didn’t like me or want me here.

The elder stopped him with just his raised hand. A silence so profound settled over the kraal, and the elder looked at me. “He stay. He be ghost of Kafir.” He nodded sagely. “He stay with Damu.”