Read Blood in the Snow, Blood on the Grass Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Blood in the Snow, Blood on the Grass (40 page)

Armed FFI men roughly bundled their shaven victims off the platform and on to the back of a flatbed truck. With two armed guards jeering at them, their shame was then paraded around the town for two hours, the klaxon blaring to attract attention. For the same reason, the driver made a long halt outside the hairdressing salon, where a number of Marie-Rose’s clients were watching. None of them showed what they were thinking, except for a mild-mannered little music teacher who had taught her in the

collège.

He came up to the truck and took both her hands in his. Ignoring the FFI men and the crowd staring at them, he said, ‘

Courage! Ça va bientôt se terminer

’

– ‘Bear up, it’ll soon be over.’

It was his sympathy that broke the dam of her self-control. Tears streaming down her face, Marie-Rose was driven away with the other shorn women and again locked up in the

collège.

A guard whom she knew told them their ordeal was over and they would soon be released. Neither of her parents came to visit Marie-Rose, but her brother brought food several times during the next four days’ confinement. One day at 0600hrs the women were released, the time being chosen because few people would be in the streets to see them. Setting out to walk the few miles back to her parents’ home, Marie-Rose was given a lift by a Spanish refugee who had lived in Valence since the civil war. On the way, he tried to comfort her with the reflection that most people soon forget everything, both the good and the bad.

For a week she dared not set foot outside, but then courageously decided that the first step in re-starting her life was to make herself a wig, so she could get back to work. As she says, ‘I was lucky. At least I knew how to do that for myself.’

Re-opening the salon, she found that, far from losing customers, all the regulars came back as though nothing had happened. In addition, a whole crop of new customers booked appointments as a tacit gesture of sympathy from the women of the town. Marie-Rose Dupont corresponded with Willi for a year without ever mentioning her public humiliation. Twelve months after her day of shame, with her natural hair fully re-grown, she left Valence and its memories and found work in a hairdressing salon at Nice. When a male colleague fell in love with her, she told him about Willi. He said, ‘We’ll pull the curtain on the past. It’s all over and done with.’

His price for marrying her and accepting her son was that she destroy all her carefully hoarded letters and photographs. After they set up home in Valence – she to re-open her salon and he working as travelling rep for a hair products company – it seemed that everyone had forgotten the shearing. Then, to her horror, she came into the salon one day and found her 8-year-old son sitting in one of the chairs, totally bald with a pair of clippers in his hand. Of her humiliation in September 1944, she never spoke again to him or anyone else until interviewed by the author in January 2006.

Notes

1

Her name and the name of the town have been changed at her request.

2

Saubaber, D.,

Pour l’amour d’un Boche

, quoted by Guilloteau in

L’Express

, 31 May 2004.

3

Marie-Rose’s story is as recounted by her to the author.

What did they achieve at such disproportionately high cost in lives, suffering and grief, the Resistance and the Maquis? There is no question that the widespread sabotage of railway communications in the run-up to, and after, the Normandy invasion was instrumental in its success by denying urgently needed reinforcements and materiel to the German forces on the Western Front. The spare parts for Lammerding’s tanks thus delayed are one example of many. Some of the intelligence culled by SOE agents and Resistance networks throughout the occupation was also of critical importance in selecting important targets for Allied strategic bombing raids – none more so than the courageously stolen details of the V1 launching sites that were brought into operation one week after D-Day to bombard London into submission, but were then swiftly bombed out of existence, thanks to this intelligence.

Yet the decision to form underground armies composed of heroic amateurs – and there were many lesser-known such groups in addition to those in the Glières, the Vercors, at Mount Mouchet and Mount Gargan – flouted all the canons of guerrilla warfare and proved those 2,500-year-old canons valid: never concentrate your forces and never be drawn into a pitched battle. Much French blood was shed in this way during late 1943 and 1944 to no apparent military gain. The premature liberation of individual towns before and after D-Day – but long before the invasion forces could possibly reach them – were, as Georges Guingouin fortunately realised, at best just bravado that invited reprisals against the civilian inhabitants and at worst acts in a sinister drama staged by the PCF.

After the liberation of France was completed on the day after

Germany’s unconditional surrender of 8 May 1945, it was understandable that French and other Allied leaders spoke highly of the courage of the male and female volunteer fighters who suffered so cruelly at the hands of the anti-partisan forces of Generals Pflaum, von Jesser

et al.

These tributes to French heroism were politically necessary at the time when de Gaulle was reconstructing a sense of national identity in a population riven by the political divisions of the pre-war Third Republic and deeply traumatised by the horrors of the occupation and the liberation, in which Allied bombing and shelling cost the lives of many thousands of innocent French civilians in the north of France. There was also an unconscious collective guilt to be assuaged because a small minority of French people had actively collaborated with the Wehrmacht, the Waffen-SS, the SD and the Gestapo.

The resultant ‘romance of the Resistance’ enabled many people who had done nothing but keep out of trouble to feel a reflected glory, as though they had personally played a part in the struggle to free their country from alien domination. It would have been politically and morally wrong to ignore the sufferings of the families that had lost their menfolk and the women who died, often after atrocious torture, in the conviction that they were sacrificing themselves for France. For each victim tortured and killed, there was also the grief of those they left behind. At a time when modern welfare state legislation was just a dream, the lives of many thousands of children and other dependants were impoverished emotionally and materially by the loss of breadwinners and parents. Families had to leave homes that could no longer be afforded and live in undeserved poverty, unalleviated by the eventual certificate of the Legion of Honour that recognised the sacrifice of the heroic dead.

If one is, with the benefit of hindsight, to add up all the suffering, including that inflicted in the German reprisals against thousands of innocent civilians, it is impossible to complete the other side of the equation by a compensating military gain.

Allied leaders used to say, during the liberation and afterwards, that the Maquis and Resistance partisans who took on regular German forces in the summer of 1944 had diverted from the Normandy front this or that number of German divisions which might otherwise have helped to drive the Allied invasion forces back into the sea. Yet, when one looks at the military quality of the troops deployed against Clair and Anjot in the Glières, Huet in the Vercors, and Colaudon and Guingouin on Mount Mouchet and Mount Gargan – and against all the other open insurrections in France – it is hard to find many units that would have made a great difference in Normandy. These were not first-line troops like the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS units who fought so tenaciously to counter the Allied invasion – and who might well have succeeded had the Luftwaffe not been a spent force in the west, giving virtually undisputed control of the skies to the RAF and USAAF.

Pflaum’s and von Jesser’s anti-partisan troops were formed by OKW in large part as training units and were heterogeneous assemblies of men, many conscripted by force among German-occupied nations in Central and Eastern Europe and the USSR plus Soviet POWs from as far east as Central Asia. They fought in many different German uniforms. Yet, a uniform does not imbue the wearer with the fanatical motivation of the Waffen-SS Panzer divisions, nor the solid, stubborn discipline of the average Wehrmacht soldier and his officers fighting for their country’s survival at that stage of the war. Many of the conscripts, like the Czechoslovakians at Aubusson, hoped sincerely for Germany’s defeat and the eventual liberation of their countries. Cannon fodder Pflaum’s men and von Jesser’s could have been, but how effective they would have been in the front line, combating the Allied armies, navies and air forces driving through the north of France towards the Reich in the second half of 1944, is an open question.

What cannot be denied is the heroism of the French men and women, mostly but not all young, who volunteered to risk imprisonment, torture, the slow death of the concentration camps and the swifter death by firing squad – all from a spirit of patriotism. That was magnificent and should not be forgotten. Their memorials, dotted all over France and still regularly decorated with fresh flowers, are a testimony to much that is best in any nation. Losing people of this quality was a great loss to post-war France, which had already forfeited so many of its brightest and best in fighting the German invaders in the First World War.

In the 1950s the PCF displayed posters reminding voters that France had been invaded by Germany three times in seventy years

1

and occupied wholly or partially each time. Britain and North America are fortunate never to have known that humiliating experience, but in the past this was due more to geography that gave them the protection of the sea – and in Britain’s case the potent shield of the Royal Navy – than to the political astuteness of their leaders or the military prowess of their generals.

In 1940 it was easy for British people to bolster their own damaged self-esteem after the humiliation of Dunkirk by saying that the British Expeditionary Force had to retreat across the Channel in 1940 because ‘the French had lacked the will to fight’. The achievement of the

résistants

and

maquisards

who voluntarily risked torture, deportation and death unprotected by any Geneva Convention – and many of whom paid such a terrible price – demonstrates beyond all doubt how wrong that glib alibi had been.

Note

1

Including the Franco-Prussian war of 1870–71.

All translations are by the author, unless otherwise attributed.

All illustrations are from the author’s collection.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright owners. In the event of any infringement, please communicate with the author, care of the publisher.

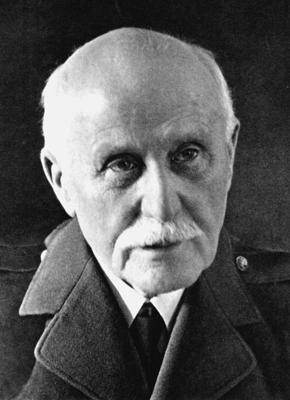

French president Philippe Pétain, who signed the armistice in June 1940.

German chancellor Adolf Hitler, who intended to bleed France dry of resources and manpower under the armistice.