Blood in the Snow, Blood on the Grass (12 page)

Read Blood in the Snow, Blood on the Grass Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

9

Noguères, p. 1569.

10

See

www.militarymuseum.org/Ortiz.html

.

11

Ibid.

12

He also received the honour of a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, the Croix de Guerre with five citations, the Médaille des Blessés, the Médaille des Evadés and the Médaille Coloniale. His other American awards included the Legion of Merit with Combat ‘V’ and two Purple Heart medals.

13

See

www.militarymuseum.org/Ortiz.html

.

146

More details on site of USMC

www.marines.mil

.

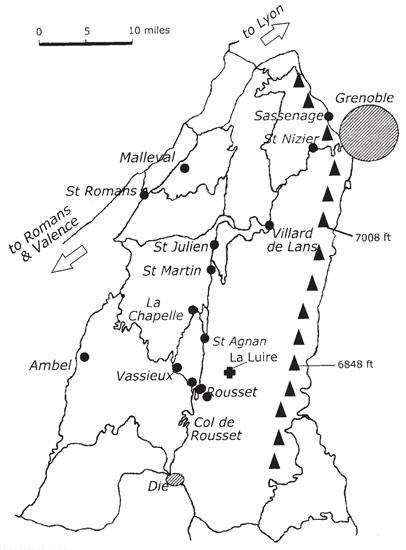

Lying some 75 miles south-west of the Glières is another limestone outcrop of the Alps that divide France from Switzerland and Italy. The Vercors plateau is an irregularly shaped block pushed upwards 1 million years ago by tectonic pressure when the African continental plate collided with the European plate. Wind, water and glaciation combined to split it into several sub-blocks separated by spectacularly deep gorges. Approximately 30 miles wide north–south by 10 miles east–west, with the near-impenetrable eastern escarpment rising sheer to over 6,000ft above sea level, the region is today primarily known for Nordic skiing in winter and for hiking, mountain cycling, rock climbing and other outdoor sports in summer. The casual visitor with an eye for natural beauty will marvel at the savage bleakness of the bare higher slopes, the forests and alpine meadows leading from them down to the valleys, the rugged gorges dropping vertiginously 1,800ft to darkness at noon and rushing water, and at the peacefully cultivated valleys with their villages and small towns seemingly untouched by time.

The tourist need never be troubled by the appalling history of the plateau, on which the locals seem – understandably – to have turned their backs. One could easily visit the sleepy village of Vassieux without seeing any sign indicating the way to the museum that tells the story of the total destruction of the village and massacre of its inhabitants in 1944. Inside, the modest display was the work of one man swimming against the tide, for the authorities preferred to ignore his documentation of a horrifying episode of military incompetence and political vacillation.

The son of poor Italian immigrants who was sent out to work as a shepherd at the age of

7

, Joseph la Picirella was determined to preserve the memory of the horrors he lived through and saw with his own eyes. Although now administered by the Département de la Drôme, as museums go, Picirella’s is not large, although the exhibited photographs, weapons and other memorabilia are an impressive personal collection.

On a typical midsummer day at the height of the tourist season only a handful of people wander round the crudely fashioned showcases. A German mother in her forties translates the captions – which are in French only – for her three blonde sons. Elderly French couples wander round silently, perhaps lost in their own memories. The men tend to concentrate on the weapons, especially those they recognise and possibly used in France’s conflicts after 1945. Some bored young children play tag between the showcases. At the reception desk, a member of staff who speaks reasonable German shares a joke with another visitor from Germany who has just been photographing the carcase of a DFS-230 assault glider displayed outside, in which Waffen-SS men brought death from the sky to this peaceful place on the morning of 21 July 1944.

In addition to the usual village cemetery, there is a military one just outside Vassieux. In precise rows of identically marked graves lie 192 people who died here in the summer of 1944. It is called

Le Necropole de la Résistance

and some headstones mark the graves of officers and soldiers of the FFI with their rank at time of death, as one would expect in a war cemetery. Two of these stones display, instead of the Christian cross, the crescent of Islam. The visitor who takes the trouble to scan every headstone will swiftly notice that one-third of the markers are simply designated ‘Unknown’

because the body buried beneath was too badly damaged by torture and/or explosions and/or fire to be identifiable, or even sexed, with the means available in 1944. Most surprising of all, in a military cemetery, is that one-third of the headstones bear female names.

Marie Blanc was a 91-year-old great-grandmother when she was killed on 14 July 1944. Jacqueline Blanc was 7 when she was killed on 21 July, the same day as her 4-year-old sister Danielle and 18-month-old brother Maurice. Suzanne Blanc was 20 when she died on 31 July, the same day as her sister Arlette, aged 12. The spread of dates tells its own story: this was no isolated air raid, no single skirmish that resulted in the deaths of defenceless civilians, but a sustained three-week campaign of terror and torture that began with bombing and strafing civilian targets on 14 July 1944 and escalated to sheer barbarity after the German gliders landed just outside the village limits one week later. The skeleton of one DFS-230 is still airborne just outside the cemetery, supported by a steel girder as mute evidence of what happened. Still in place is the single row of ten metal passenger seat frames, one behind the other, on which sat the killers of Jacqueline, Danielle and Maurice.

To begin the sequence of events that led to their deaths, it is necessary to turn the pages back four years exactly – to June 1940, when a refugee Parisian architect named Pierre Dalloz came to live in the small town of Sassenage at the foot of the north-eastern escarpment. Being a keen mountaineer, he explored the Vercors, which seemed to him, with its few access routes between unscalable cliffs and its generally hostile terrain, such a remote area that it could become what he likened to a Trojan horse.

Rather carried away by his simile, he was convinced that a small force of irregulars installed on the heights could easily block the steep and twisting access roads which the German forces based in Grenoble, standing literally in the shadow of the eastern escarpment, would use in any attack. The irregulars could then convert the plateau into an inland bridgehead, so Dalloz thought, where Allied airborne troops could safely be landed, and from where they could sally out to cut off German forces retreating along the Rhône valley after an eventual invasion of southern France.

The idea was simple, but the term ‘plateau’ is misleading because the Vercors has very little level terrain, even in the inhabited parts which lie generally at 3,000ft-plus above sea level. In addition, a deep gorge running south-west–north-east divides the massif in two, making it difficult if not impossible for defenders on one part of the plateau to come rapidly to the support of comrades under threat on the other part.

The Vercors plateau.

After the Germans occupied the Free Zone in November 1942 Dalloz and his friend Jean Prévost persuaded the Lyonnais journalist Yves Farge, whom they knew to be active in the Resistance, to put this somewhat sketchy ‘plan’ to Jean Moulin. Moulin, who had no military experience, gave it the seal of his approval in January 1943. In keeping with de Gaulle’s wishes that the liberation of France be seen to have been accomplished at least partially by French forces, General Delestraint also approved the Dalloz plan and ‘sold’ it to BCRA in London.

The first Maquis band established itself in 1942 at a remote farm on the western side of the plateau named Ambel, where they were joined by thirty Polish-Jewish refugees and a Jewish doctor from Alsace. At an altitude of over 3,000ft, winter conditions were harsh. By the end of April 1943 there were nine or ten bands installed separately on the plateau, mostly commanded by professional army officers from Vichy’s disbanded Armée de l’Armistice, who insisted on a semblance of military discipline: a morning parade with saluting of the French flag and some drilling with weapons.

By November 1943 there were an estimated 30,000

maquisards

spread out all over France, but only 250 were in the Vercors. On 13 November 1943 came the first arms drop, enabling each group to have a few Sten guns to add to a collection of outdated firearms, relics of the First World War.

An observant volunteer

with an enquiring mind was Gilbert Joseph, who had fled Paris aged 17 to avoid the STO and took a job overseeing the boarders in a small school at Villard de Lans, a winter sports resort in the Vercors, whose normal population was swollen by people with reason to feel insecure in the Vichy state but relatively safe up there. Hotels, chalets and apartments in Villard and the neighbouring communes were temporarily home to an assortment of refugees with money and some poorer ones like Joseph who had to work. Those with money spent it fast, as though living on the edge of the abyss. The black market flourished. The local Gendarmerie officers ranged from some positively helpful to the refugees and

maquisards

to the majority who simply turned a blind eye.

The golden youth, as Joseph called it, paraded in fashionable clothes after rising late, visited the cinema and attended dances while their elders played interminable games of bridge and exchanged wild rumours about the war. From time to time a German column drove up from Grenoble, usually at night, but failed to dent the sense of security for long because their approach was signalled by the ringing of church bells in Villard. A loudspeaker truck toured the streets, warning all the young men to leave town until the danger was past and the game of

dolce far niente

could re-start.

1

After contacting a local woman known to have links with the Resistance in the autumn of 1943, Joseph told the headmaster of his decision to leave and join the Maquis. The reaction was an outburst of sardonic laughter: ‘War, my boy, is shit, mud and blood.’ Undeterred, Joseph followed a complicated route to a

camp de triage

where would-be recruits were tested for physical endurance and questioned on their political views before finally being sent on to one Maquis band or another.

Walking through Grenoble on his way to catch a bus back up to Villard, he noticed that people no longer looked each other in the eyes. There were no other young men in the streets. Anyone young enough and physically fit for STO conscription, especially if wearing weather-proof clothing or stout boots or carrying a rucksack of provisions, risked being stopped at any moment by police auxiliaries called

physionomistes

who ordered their victims to lower their trousers in search of a circumcised penis. Among their prey were also STO no-shows like Joseph.

2

In November 1943 Dalloz made his way through Spain to French North Africa, from where he was flown to London to explain in detail his plan for the Vercors, which BCRA code-named Operation Montagnards. Dalloz was quite explicit that there could be no question of using the Vercors as a base from which the Maquis could attack German regular forces, nor turn it into an entrenched fortress. Its purpose, he repeated, was to provide a safe landing ground for Allied airborne troops or paratroops when the German forces in the area were already in disarray. Taking advantage of this, local

maquisards

could guide Allied incomers to where they could inflict the maximum damage on the enemy.

3

In other words, the military purpose of the redoubt was to be fulfilled

after the invasion and in conjunction with trained Allied troops.

On being demobilised from the Armée de l’Armistice on 4 December 1943, Joseph la Picirella told his mother that he had decided to join the Maquis. She was distraught, having seen her younger son deported to Germany shortly before. He arrived on the plateau in the depths of winter, to find himself one of the few volunteers with any military experience. The difference between talk and action is illustrated by a mention in Picirella’s diary saying that he was meant to have gone to the Vercors in a group of eighteen, of whom only two actually turned up there. Their arrival at the foot of the plateau was greeted with disbelief by a postman of whom the two young men asked the way to Maquis HQ.

‘You’re going to St-Martin?’ he asked them incredulously. ‘You’re crazy. There’s more than a metre of snow on the road and the mail hasn’t got through these last three days.’