Blood-Dark Track (41 page)

Authors: Joseph O'Neill

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Literary

Many Armenians avoided harm by fleeing to Mersin, where some caught boats to Cyprus. That Mersin saw no violence was, according to Doughty Wylie, largely due to the governor-general of Mersin – ‘the first Ottoman official there to refuse bribes and to refuse to be entirely ruled by the Greek clique’. Mersin was also the base of a flotilla of French and British warships that arrived soon after news of massacres spread abroad. The surgeon aboard the HMS

Swiftsure

, which sailed into Mersin on 21 April, went ashore to treat patients in makeshift hospitals. ‘The brutality and savagery of the massacre are impossible to describe,’ he later reported, noting, in descending order of frequency, wounds caused by Martini rifle bullets; swords and hatchets; clubs and sharp sticks; Mauser and revolver bullets; and bayonets.

The international naval presence had a limited deterrent effect. On the night of 25 April, there were further killings in Adana, and the Armenian quarter was burned to rubble. The statistic emerged that of the 4823 properties destroyed, 4437 belonged to Armenians.

Doughty Wylie was at a loss to explain the two massacres and by what devilry, as he put it, the Turkish peasant, ‘a kindly, honest and hospitable man, can suddenly be changed into a cruel killer of unarmed men and even in some cases of women and children’. On further reflection, he identified a variety of factors. The constitution recently proclaimed by the Young Turk government, under which Christians enjoyed equality with Muslims, was deeply

offensive to the Muslim Turks. This resentment was inflamed by the ‘swaggering’ behaviour of the Christians, who, ‘with all the assertiveness of the newly emancipated, made equality to seem superiority’. This unseemly behaviour included the flaunting of weapons bought under a freshly acquired right to bear arms, and loud talk of what Doughty Wylie called ‘Home Rule’ – the establishment, with assistance of foreign powers, of an Armenian principality in Cilicia. The British consul, who regarded such talk as patently fantastical and ineffectual, commented that the ‘incurably loquacious’ Armenians ‘never seem to have thought of the possible consequences of wild words. Natives of the country, they should have known its dangers, but with the word liberty they forgot them all.’

It was against this backdrop of communal hostility that, on Thursday 8 April, an Armenian shot dead two Turks. The funeral of the men, whose bodies were carried through the town, provoked strong feelings among the ‘savage, ignorant, and fanatical’ Turks, who misconstrued the incident as a seditious attack. The atmosphere in Adana worsened, and it was at this time that Armenians who could afford to do so began to flee by train to Mersin. On Wednesday 14 April, the uneasiness was so great that shops closed and groups of armed Muslims began to gather on the streets, saying the Armenians were going to revolt; some Armenians, in their turn, regrouped and assumed defensive positions. Then, shots were fired – who fired first was never established – and the killing began. Major Doughty Wylie concluded that the real fault lay with the local Ottoman authorities, whose response to the events was culpably feeble. He found that the Muslim violence, although inexcusable, had in the main been committed by persons gripped by a real fear for their Empire, their religion and their lives. The consul (who was to be killed by Turks in 1915, leading a charge on the Gallipoli peninsula) observed, ‘Nothing is so cruel as fear.’

Meanwhile in Iskenderun, where the Dakak family lived, trouble started after rumours spread from Adana of violent Armenian insurrection. On 17 April, Muslims – Turks, Kurds, Circassians – armed with revolvers, long knives, and guns plundered from

military stores, began to march about the town in white turbans and to terrorize the rural Christian populace; houses and hamlets in the hills surrounding Iskenderun could be seen in flames. That evening, the British Honorary Consul, Joseph Catoni, reported, ‘A large number of families left Alexandretta by the Austrian mail steamer for Cyprus.’ In the steamer, it could safely be inferred, travelled Caro and Basile Dakak and their three children – who included, of course, my nine-year-old grandfather.

On 30 June 1909, the representatives of the Christian communities – Gregorian, Armenian, Protestant, Roman Catholic, Syrian, Greek Catholic, and Chaldaean – made the following public declaration:

The Christians of the district and city of Adana desire to express their deep regret concerning the great misfortune which has befallen them, and the false imputation raised against them. They desire to make declaration as to their real position.

We, the Christians of Adana and adjacent districts, have been faithful to the constitution from the time of its proclamation, and we earnestly desire its continuance and success. As true Ottoman subjects, our desire and effort has been to protect the constitution and to be found on the side of those who love and serve it. We emphatically protest against all imputations of rebellion made against us. We have never rebelled, and the idea of rebellion has never entered our minds. We, although loyal subjects, have suffered and been persecuted, and we have been sacrificed to the envy and malevolence of bigoted and evil-minded persons. We are the victims of machinations and schemes which caused heaven and earth to weep and wonder. Our loyalty to the Government is proved by the fact that in the very beginning of the troubles we appealed for Government protection, and later, on the first possible opportunity, we renewed our appeal.

We again declare our loyalty to the constitution. We are ready and eager to make any sacrifice for the true welfare of our beloved land, and we declare also that we cherish no spirit of revenge, notwithstanding the suffering which we have endured. Our earnest plea to our Muslim fellow countrymen is that they should work in harmony with the various other communities which compose the Ottoman Empire. May the goodwill and fellowship which appeared at the time of the proclamation of the constitution appear again!.… Let unity, fraternity, equality and justice prevail.…

As I read this pathetic announcement – all the more poignant if one looked back on it, as I later did, with knowledge of the apocalypse looming for the Armenians – I felt ashamed that I’d always held against my Turkish family and friends their aloofness from such issues as the oppression of Turkish Kurds. I’d had no real idea of the cost of political action in Turkey or of the abysmal hazards that faced a Christian Turk.

As for Joseph, I realized that, like Jim O’Neill, he had grown up in a malignant, dreadful world that had marked him in ways I had yet to evaluate.

A

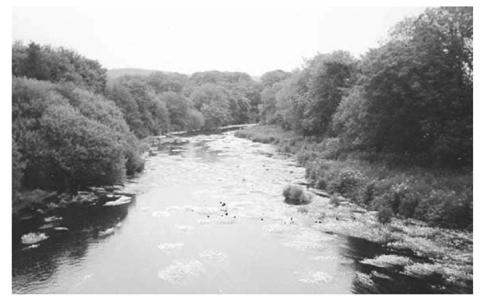

few days after returning from the north of Ireland with Brendan, I drove out to West Cork to take a stroll by the river. However, when I reached Manch, the scene of so many famous poaching adventures, I impulsively swung the car through the gates of the Manch estate. Somewhere in these woods, in some Big House I’d never seen, lived the Conner family, whose exclusive fishing rights over stretches of the Bandon had been persistently violated by generations of my own family. For all I knew, nobody in my family had laid eyes on the house, at least not from the perspective of a visitor winding his way up the drive to make a social call. I drove past a meadow and then slowly up a driveway that curved through rhododendron bushes and thick forest. Manch House appeared in a clearing in the woods. It stood at the far end of a small fairway, a large, graciously proportioned, pale-stoned building with

a tower and a view of the valley that, by a trick of landscaping, was unreciprocated.

I had barely stopped the engine before a cat and three dogs, including an enormous Irish wolfhound, had surrounded the car. A white-haired, white-bearded fellow in his late fifties, who later introduced himself as Con (Cornelius) Conner, came out slowly with his hands in his pockets and asked if he could help me. I explained that I was a member of the O’Neill family, from Ardkitt, and that I was researching my grandfather’s poaching antics on the river. Conner, a quiet-spoken, glumly humorous man with a soft English-Irish accent, did not know about any Ardkitt O’Neills, but he confirmed that his family owned about two miles of fishing rights. His father had given over a stretch of the river to the public in the hope of dissuading poachers, he said, but it was a crappy stretch and of course the ploy didn’t work. A jeepload of bailiffs still wandered around the river now and again, Conner said gloomily. Their duties were diffuse these days, and they even went out to sea in a fast boat that came courtesy of the EC. There wasn’t much poaching at all any more, Conner said, although needless to say there were still some idiots who took disproportionate risks, including some who engaged in an obscene competition to catch the most trout using a worm bait. There weren’t the number of fish there used to be and the incentive to poach disappeared once salmon farming made the fish available to the masses. In the old days, things were different. He could remember selling an 18lb salmon for £5 in 1952, when land cost £50 an acre.

Con Conner mentioned that he was The O’Connor Kerry – the chief of the O’Connor Kerry clan. ‘We have our own little world,’ he volunteered with an air of faint dismay. ‘We’re West British, really; our cultural feelings would be closely tied to British culture. My father was on the English side to begin with,’ he continued, seamlessly moving on to the subject of the Troubles, ‘but then joined Fine Gael when the British failed to shoot de Valera after they captured him in 1916.’ The family hadn’t always been unionist or pro-establishment in sentiment, he added. The brothers

Arthur and Roger O’Connor were leading figures in the 1798 rebellion, and next year a monument was to be erected at Manch to commemorate them and the two hundredth anniversary of the rebellion.

He invited me into the house, which was built in 1826; the oldest Conner residence, the seventeenth century Carrigmore House, stood elsewhere on the estate. The ground floor living quarters had the chaotic, dustily charming ambience of a jumble sale. There was a clutter of old family portraits, old bits of furniture, and a giant old stove heater; and to complete the picture of decaying Ascendancy privilege, Oriana Conner, Con’s wife, was seated in a corner of the kitchen totting up bills with the help of an associate. Over a cup of tea, I spoke a little about my family’s years of theft on their stretch of the river. Oriana – an Irishwoman with an English accent – laughed, saying that families needed to be fed. We talked amiably for a while longer, and then the Conners showed me around the two self-contained apartments they had created for paying guests. As I left they placed a brochure and advertisement slips in my hand and urged me to tell my fishing friends at the English Bar to come over. Non-fishing guests would also find the Manch House Fishery to their liking, the brochure assured me. Riding, golf, sightseeing, gourmet restaurants and great pubs were all within easy reach. There was fresh organic produce available from the Manch organic farm, where a flock of milk sheep, poultry, and outdoor pigs lived pleasant, non-intensive lives. Over half of the estate was given over to organic farming; the rest of the estate was broadleaf woodland. A signed handwritten message appeared at the end of the brochure:

We enjoy sharing with our guests the beauty and tranquillity of Manch and the Bandon river. We want you to have a thoroughly enjoyable holiday and will do our best to make it so. Con and Oriana

.

I drove out of the Manch estate marvelling at the social reduction of these once-so-powerful families, whose way of life, which once turned on fastidious exclusiveness, now depended on the number of strangers they could persuade to stay in their homes. The change was, in its way, revolutionary. Moreover, by my unannounced visit

the ancient, quasi-mystical distance that had separated the Conners and the O’Neills had suddenly shrunk to more normal proportions. They would no longer seem quite as powerful and strange and inhuman, and perhaps we, in the light of day, might no longer figure as purely anonymous shadows moving around the black river.

I stopped the car a couple of hundred yards away, by the Conner’s West Farm, and parked on the verge of the road. I knew, from a recent visit here with my uncles Brendan and Jim, that the river flowed very close by, unseen behind hedges and greenery. I climbed over a locked gate (no entry was permitted without authorization, a sign declared) and walked through uneven grassland, some of it thigh-high, toward the river. I stepped over the defunct track of the old railway line. I came to the river. A black concrete ridge had in recent years been built into the bank as a fortification against the erosive current. Waste paper and a plastic bottle disclosed that someone had not long ago been fishing here. On the far side of the river were open fields; to the east, about half a mile away by the Curraghcrowley townland, was a wooded height. Kilcascan Castle, the only other Big House in the locality and the former home of the O’Neill Daunt family (no relation), was hidden

by the magnificent hilltop trees, in the shelter of which my grandfather’s getaway car had sometimes been parked.

I was standing by the pool known as the Key Hole, which even in daylight was like a still pool of ink. I tossed a stone into the pool; no salmon moved. I remembered that in the Skibbereen

Southern Star

of 4 February 1956, there had appeared a report about an action brought by Henry Conner, of Manch House, against Cork County Council in respect of loss suffered as a result of a poisoning of the Key Hole with bluestone by unknown poachers acting out of revenge. Six salmon – valued at £49 16s. 0d. – and 35 brown trout had been killed.