Blood Brotherhoods (81 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

all the heads of the secret services, 195 officers of the various armed corps of the Republic, among whom were twelve generals of the

Carabinieri

, five of the Tax Police, twenty-two of the army, four of the air force and eight admirals. There were leading magistrates, a few prefects and Police Chiefs, bankers and businessmen, civil servants, journalists and broadcasters.

There were also forty-four members of parliament, including three government ministers. Among the businessmen on the list was an entrepreneur who could not yet be called a member of the establishment: Silvio Berlusconi. It is often not clear what individual members of P2 like Berlusconi thought its aims really were. But the power of the lodge is not in question: in 1977 it took control of Italy’s most influential newspaper,

Corriere della Sera

. The very least that can be said about P2 is that it showed how, in the face of the growing influence of the Communist Party (which reached its highest ever percentage of the popular vote in the general election of 1976), key members of the elites of both power and money were closing ranks and establishing covert channels of influence.

P2 was far from the only aberrant Masonic society to emerge at this time.

Mafiosi

wanted in on the act. Cosa Nostra was making similar moves to the ’ndrangheta. According to several defectors from the ranks of the Sicilian mafia, between 1977 and 1979 a number of its most senior men joined Masonic organisations too. The issue of Masonic affiliation was discussed at Cosa Nostra’s Regional Commission in 1977.

The mafias’ alliance with Freemasonry in the 1970s showed underworld history coming full-circle. For the very origins of Italy’s secret criminal brotherhoods lay in contacts between Masonic conspirators who successfully plotted to unite Italy in the first half of the nineteenth century, and the hoodlums those patriotic conspirators recruited as revolutionary muscle. Then, as now, the thing Italy’s hoodlums prized most about Freemasonry was contacts. As Leonardo Messina, a Sicilian

mafioso

who defected from Cosa Nostra in 1992, explained:

Many men in Cosa Nostra—the ones who managed to become bosses, that is—belonged to the Freemasonry. In the Masons you can have contacts with entrepreneurs, the institutions, the men who manage power. The Masonry is a meeting place for everyone.

So for the ’ndrangheta, the Mamma Santissima was a new constitutional device for regulating the Calabrian underworld’s connections with the upper world of politics, business and policing.

When it was first introduced, the Mamma Santissima was highly controversial: many considered it a ‘bastardisation’ of the Honoured Society’s rules. Indeed the innovation drove a wedge between the members of the triumvirate. Mommo Piromalli supported it, whereas Mico Tripodo was against it. It is said that don ’Ntoni Macrì, the ’ndrangheta’s patriarch, the ‘living symbol of organised crime’s omnipotence and invincibility’ who danced a mean

tarantella

, was viscerally opposed.

Why the resistance? Some say that the grounds for don ’Ntoni’s opposition to the Mamma Santissima were simply that he was traditional, a man loyal to the old rules. This explanation seems implausible to me, dripping in nostalgia for some good old mafia that has actually never existed. If don ’Ntoni was like every other

mafioso

there has ever been, then he obeyed the traditional rules only for as long as it suited his interests.

No, the real reason why don ’Ntoni Macrì was opposed to the Mamma Santissima was simply that he was excluded from it. In fact, I suspect that the new gift was invented with the precise aim of cutting him out, of isolating him from important secrets. And behind that manoeuvre lay a plan to stop don ’Ntoni meddling in other people’s kidnappings, and—even more importantly—to keep his grasping hands away from the Colombo package (the publicly funded construction bonanza that came following the Reggio revolt of 1970). It was through contacts with the local ruling class, and in particular with Masonic brotherhoods, that the bonanza was to be distributed. It is no coincidence that among the main proponents of the Mamma Santissima was don Mommo Piromalli, the triumvir who hailed from Gioia Tauro where the new steelworks was going to be built. In the world of the mafias (and not just the mafias), constitutional innovation is often just a mask for skulduggery.

Between them, the De Stefano brothers’ ambitions in Reggio Calabria and the tensions between the triumvirs over the Mamma Santissima and the Colombo package would push the ’ndrangheta into war.

In September 1974, Mommo Piromalli hosted a meeting of the ’ndrangheta’s chiefs in Gioia Tauro. Among those in attendance were not just the other triumvirate members—don ’Ntoni Macrì from the Ionian coast and the bigamist Mico Tripodo from Reggio—but also don Mico’s pushy underlings, the De Stefano brothers. Unanimously, the bosses rejected an offer from major construction companies: a 3 per cent cut of profits from construction of the Gioia Tauro steelworks. The ’ndrangheta would not be happy unless its share was fattened out by contracts and subcontracts. Nonetheless tensions within the brotherhood in Reggio spilled over: Mico Tripodo and Giorgio De Stefano exchanged acid words, and only the intervention of don ’Ntoni Macrì—posing, as ever, as the peacemaker—prevented a violent confrontation.

Another attempt to preserve the peace in Reggio Calabria soon followed. This time the occasion was not a business meeting but a wedding reception in the Jolly Hotel in Gioia Tauro. The father of the bride was one of the Mazzaferro clan, close allies of Mommo Piromalli, and the celebrations were attended by chief cudgels from across Calabria. Fearing an ambush, Mico Tripodo did not attend, and paid for his absence by being insulted by the Comet’s younger brother Paolo. Again don ’Ntoni tried to calm the waters, and plans were laid for a third meeting on neutral territory—Naples.

But by this time it had become clear to all involved that any outbreak of fighting between the De Stefanos and don Mico Tripodo in Reggio Calabria would draw other

’ndrine

in. Behind don Mico stood ’Ntoni Macrì. And behind the De Stefanos stood Mommo Piromalli in Gioia Tauro. So what had initially seemed like a local matter, a familiar confrontation between an older boss and younger men trying to oust him, had grown into a fracture dividing the whole ’ndrangheta into two alliances, both of them prepared for war. The equilibrium that the triumvirate had guaranteed for a decade and a half had been fatally destabilised.

On 24 November 1974, at around eight o’clock in the evening, two killers entered the fashionable Roof Garden bar, a notorious ’ndrangheta hang-out in Reggio Calabria’s piazza Indipendenza. Scanning the room, the two quickly identified the table where their targets were sitting. The first assassin pulled out a long-barrelled P38 and shot Giovanni De Stefano in the head from about a metre away. When the gun jammed, his accomplice raised another weapon and blasted two more bullets into Giovanni De Stefano’s prostrate form before firing at Giovanni’s brother Giorgio, ‘the Comet’. Although the Comet was badly wounded, he survived the Roof Garden assault; Giovanni died at the scene. Retaliation could not wait long. The conflict was now unstoppable.

Don ’Ntoni Macrì, now that he was too old to dance the

tarantella

, had the habit of playing bowls with his driver every day on the edge of town

before heading back home to hold court. On 20 January 1975 he had just finished his game and climbed back into the car when an Alfa Romeo 1750 screeched to a halt in front of him. Four men got out and let rip with pistol and machine-gun fire. Siderno shut down for the old chief cudgel’s funeral, and some 5,000 people paid their respects.

The First ’Ndrangheta War, as it is now known, caused more fatalities than Sicily’s First Mafia War of the early 1960s. There were 233 murders in three years. Local feuds in Ciminà, Cittanova, Seminara and Taurianova added to the body count. There was savagery on all sides. In one phone tap, Mommo Piromalli was heard telling his wife how he fed one of his victims to the pigs: ‘

L’anchi sulu restaru

’ (‘Only his thigh bones were left over’), he explained. ‘Oh yes!’ she replied.

A score of the old bosses fell. The last (and the most important after ’Ntoni Macrì) was the bigamist and triumvir don Mico Tripodo. In the spring of 1976, he was arrested with his camorra friends in Mondragone and sent to Poggioreale prison in Naples. Five months later, on 26 August, two Neapolitan petty crooks cornered him in his cell and stabbed him twenty times on the orders of a camorra

capo

. The De Stefanos had shown that they too had friends in the Neapolitan underworld, and by using them to eliminate their boss and enemy Mico Tripodo, they brought the war to a close.

Or not quite to a close. On 7 November 1977, Giorgio ‘the Comet’ De Stefano took the risk of leaving his patch in Reggio Calabria to attend an important meeting of the ’ndrangheta’s upper echelons up on Aspromonte. Before proceedings got under way, he sat down on a rock to light a cigar. Suddenly, there came a shout: ‘

Curnutu, tu sparasti a me frati

’ (‘You cuckold, you shot my brother’); it was followed immediately by gunshots. The Comet, the apparent victor of the First ’Ndrangheta War, and the supposed epitome of the modern

mafioso

, had only been allowed a year to enjoy the fruits of his military success.

For a moment, it looked as if the Comet’s surviving brother Paolo De Stefano would push the ’ndrangheta into another war. But internal investigations soon discovered that the hit-man was a low-ranking affiliate called Giuseppe Suraci. Paolo De Stefano was told that Suraci just had a personal beef. The other bosses who had seen the Comet die placated Paolo De Stefano’s vengeful wrath by presenting him with Giuseppe Suraci’s severed head. This grisly gesture re-established the peace that had taken shape after the war of 1974–6.

We now know, however, that the version of the Comet’s murder told to Paolo De Stefano by the other ’ndrangheta bosses was an ingeniously crafted lie. The killer Giuseppe Suraci had not acted out of personal vendetta, but because he was ordered to by the De Stefanos’ allies in the First ’Ndrangheta

War, the Piromallis. He was then beheaded to prevent him from being interrogated by Paolo De Stefano about why he had

really

killed his brother.

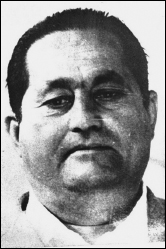

Head of a crime dynasty. Girolamo ‘Mommo’ Piromalli pictured in 1974, the year the First ’Ndrangheta War broke out. Don Mommo would emerge victorious.

By the time of the Comet’s death, Mommo Piromalli was semi-retired, leaving the clan’s day-to-day business to his younger brother Giuseppe. And Giuseppe had taken objection to the way Giorgio ‘the Comet’ De Stefano had extorted a bribe from a building contractor who was already under Piromalli protection. Thus the Comet had committed a

sgarro

: an insult to a mobster’s authority and honour. That

sgarro

was enough to draw a death sentence down on its perpetrator. The Piromallis had, deviously and ruthlessly, cut their upstart former allies down to size.

So it was Mommo Piromalli’s clan who were the real winners of the First ’Ndrangheta War. The core reason for the Piromallis’ success was their political shrewdness. Mommo Piromalli joined the triumvirate in keeping the equilibrium for as long as it suited him. He then proposed the Mamma Santissima when the time came to isolate his enemies. He used the Comet against his enemies too; and then used a trick to dispose of him.

Mommo Piromalli was the only member of the triumvirate that ruled the ’ndrangheta since the 1960s who died of natural causes. Cirrhosis of the liver carried him away in a prison hospital in 1979. He left behind him a clan more powerful than any in Calabria. Still to this day, the Piromallis are a major force. As, for that matter, are their allies in the First ’Ndrangheta War, the De Stefano family.

By the late 1970s, however, the Mamma Santissima had already been overtaken. As one ’ndrangheta defector has explained, the number of

santisti

rapidly increased, making it necessary to introduce new, higher gifts above their rank: