Blood Brotherhoods (107 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

On 9 August 1991, the Calabrian magistrate Nino Scopelliti was on his way home from the beach when he was ambushed on a road overlooking the Straits of Messina. Scopelliti was due to present the prosecution’s case in the maxi-trial to the Supreme Court. To this day, his murder remains unsolved, although the most likely scenario is that Cosa Nostra asked the ’ndrangheta to kill him as a favour. It is thought that the peace that finally put an end to the Second ’Ndrangheta War at around this time was brokered by Cosa Nostra as part of the deal. Today, a monument marks the spot where Scopelliti’s BMW crashed to a halt: it shows a winged angel on her knees, holding the scales of justice.

Shorty Riina made his men promises. He told them that Cosa Nostra’s tame politicians, notably ‘Young Turk’ Salvo Lima, would pull strings to ensure that the final stage of the maxi-trial would go their way. He claimed that the case would be entrusted to a section of the Supreme Court presided over by Judge Corrado Carnevale, whose tendency to overturn mafia convictions on hair-splitting legal technicalities had earned him newspaper notoriety as

the ‘Verdict Killer’. Judge Carnevale made no secret of his disdain for the Buscetta theorem.

Despite these promises, by the end of 1991 Cosa Nostra knew that the battle over the maxi-trial was likely to be lost. In October Falcone managed to arrange for the maxi-trial hearing to be rotated away from the Verdict Killer’s section of the Supreme Court. Shorty called his men from across Sicily to a meeting near Enna, in the centre of the island, to prepare the organisation’s response to the Supreme Court ruling. The time had come to take up their weapons, he said. The plan was to ‘wage war on the state first, so as to mould the peace afterwards’. The mafia’s dormant death sentences against Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino were reactivated. As it had always done, Cosa Nostra was going to negotiate with the state with a gun in its hand. But this time, the stakes would be higher than ever.

On 30 January 1992, the Supreme Court issued its ruling and re-established the maxi-trial’s original verdict. The Buscetta theorem had become fact. Cosa Nostra existed in the eyes of the Italian law. When the news broke, Giovanni Falcone was in a meeting in the Ministry of Justice with a magistrate who had come all the way from Japan to seek his advice. Falcone smiled and told him what the maxi-trial’s final outcome meant: ‘My country has not yet grasped what has happened. This is something historic: this result has shattered the myth that the mafia cannot be punished.’

It was equally evident to Falcone’s enemies how significant the Supreme Court verdict was. Shorty Riina’s brutality had cut Cosa Nostra off from its political protectors. His leadership would be called into question, and his life was inevitably forfeit. The boss of all bosses declared that Cosa Nostra had been betrayed, and was entitled to take vengeance. His leading killer has since told judges that Cosa Nostra set out to ‘destroy Giulio Andreotti’s political faction led [in Sicily] by Salvo Lima’. Without Lima and Sicily, Andreotti would lose much of his influence within the DC. Thus, less than six weeks after the Supreme Court’s ruling on the Buscetta theorem, Salvo Lima received his reward for forty years of service to Cosa Nostra when he was gunned down in the Palermo beach suburb of Mondello by two men on a motorbike.

Falcone understood the ground-shaking implications of Lima’s execution. As he said to a magistrate who was with him when the news broke: ‘Don’t you understand? You must realise that an equilibrium has been broken, and the entire building could collapse. From now, we don’t know what will happen, in the sense that anything may happen.’

With the establishment of the DIA, the DNA and the DDAs, the confirmation of the Buscetta theorem, the political orphaning of Cosa Nostra, and finally the murder of Salvo Lima, Falcone’s brief months in the Ministry of Justice saw the dawn of an entirely new epoch in the long history of Italy’s relationship with the mafias. An epoch we are still living in. An epoch born to the sound of bombs.

THE FALL OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC

S

ACRIFICE

A

T

17.56

AND FORTY-EIGHT SECONDS ON

23 M

AY

1992,

AT THE GEOLOGICAL

observatory at Monte Cammarata near Agrigento in southern Sicily, seismograph needles jumped in unison. Sixteen seconds earlier, and sixty-five kilometres away, a stretch of motorway leading back to Palermo from the city’s airport had been torn asunder by a colossal explosion.

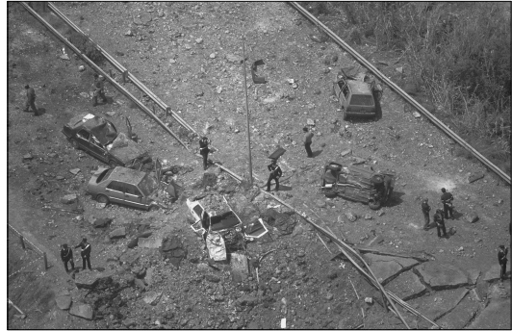

At the scene of the explosion, three policemen, Angelo Corbo, Gaspare Cervello and Paolo Capuzza, felt a pressure wave and a flash of heat, and were thrown forwards as their car juddered to a halt under a cascade of debris. They were in the third vehicle of a three-car convoy escorting Giovanni Falcone and his wife back home to Palermo for the weekend. Groggy from the impact, they peered in horror at the devastation. Then it dawned on them that there could be a secondary assault, a death squad moving in to finish off the man under their protection. Capuzza tried to grab his M12 submachine gun, but his hands were shaking too much to pick it up. So, like the others, he opted for his service pistol. The three stumbled onto the tarmac. Falcone’s white FIAT Croma lay a few metres away, pitched forwards, on the edge of a four-metre-deep crater. Falcone sat in the driver’s seat behind a bulletproof door that refused to budge. Gaspare Cervello later recounted the scene: ‘The only thing I could do was to call Judge Falcone. “Giovanni, Giovanni.” He turned towards me, but he had a blank, abandoned look in his eyes.’

Giovanni Falcone and Francesca Morvillo died in hospital that evening. Three of their bodyguards—Vito Schifani, Rocco Dicillo and Antonio

Montinaro—were already dead: they were in the lead car of the convoy that took the full force of the detonation.

The Capaci massacre, 23 May 1992. Falcone, his wife and three of their bodyguards were murdered by a bomb placed under the motorway leading back to Palermo from the airport.

What makes a hero? Where did Falcone get his courage? After so many setbacks, so much terror? The Italian state was viewed with scorn by many of its citizens; its human and material resources were treated by all too many politicians as mere patronage fodder. Yet it was in the name of that very state that Falcone chose to give his life.

The definitive answer to those questions lies hidden in psychological depths into which no historian will ever be able to reach. All the same, the question is far from being an idle one. Indeed it is extremely historically important. Because Falcone was not alone. His cause was shared by many others—beginning with his wife and his bodyguards. After Falcone, many others would be inspired by his story, just as he had been inspired by the example of those who died before him.

When Falcone’s friends and family were asked about what drove him, they spoke of his upbringing, and the patriotism and sense of duty that were instilled in him from a young age. Such factors are undoubtedly important.

But the most insightful account of Falcone’s motives came from the man who shared his destiny.

On the evening of 23 June 1992, exactly a month after Giovanni Falcone passed away in his arms, Paolo Borsellino stood up in his local church, Santa Luisa di Marillac, to remember his great friend. As he made his way to the pulpit, the hundreds who had crowded into the candle-lit nave spontaneously got up to applaud him. Hundreds more could be heard clapping outside. Seven minutes later, his voice unsteady, Borsellino began one of the most moving speeches in Italian history:

While he carried out his work, Giovanni Falcone was perfectly well aware that one day the power of evil, the mafia, would kill him. As she stood by her man, Francesca Morvillo was perfectly well aware that she would share his lot. As they protected Falcone, his bodyguards were perfectly well aware that they too would meet the same fate. Giovanni Falcone could not be oblivious, and was not oblivious, to the extreme danger he faced—for the reason that too many colleagues and friends of his, who had followed the same path that he was now imposing on himself, had already had their lives cut short. Why did he not run away? Why did he accept this terrifying situation? Why was he not troubled? . . .

Because of love. His life was an act of love towards this city of his, towards the land where he was born. Love essentially, and above all else, means giving. Thus loving Palermo and its people meant, and still means, giving something to this land, giving everything that our moral, intellectual and professional powers allow us to give, so as to make both the city, and the nation to which it belongs, better.

Falcone began working in a new way here. By that I don’t just mean his investigative techniques. For he was also aware that the efforts made by magistrates and investigators had to be on the same wavelength as the way everyone felt. Falcone believed that the fight against the mafia was the first problem that has to be solved in our beautiful and wretched land. But that fight could not just be a detached, repressive undertaking: it also had to be a cultural, moral and even religious movement. Everyone had to be involved, and everyone had to get used to how beautiful the fresh smell of freedom is when compared to the stench of moral compromise, of indifference—of living alongside the mafia, and therefore of being complicit with it.

Nobody has lost the right, or rather the sacrosanct duty, to carry on that fight. Falcone may be dead in the flesh, but he is alive in spirit, just as our faith teaches us. If our consciences have not already woken, then they must awake. Hope has been given new life by his sacrifice, by his woman’s sacrifice, by his bodyguards’ sacrifice . . . They died for all of us, for the unjust. We have a great debt towards them and we must pay that debt joyfully by continuing their work, by doing our duty, by respecting the law—even when the law demands sacrifices of us. We must refuse to glean any benefits that we may be able to glean from the mafia system (including favours, a word in someone’s ear, a job). We must collaborate with justice, bearing witness to the values that we believe in—in which we are obliged to believe—even when we are in court. We must immediately sever any business or monetary links—even those that may seem innocuous—to anyone who is the bearer of mafia interests, whether large or small. We must fully accept this burdensome but beautiful spiritual inheritance. That way, we can show ourselves and the world that Falcone lives.