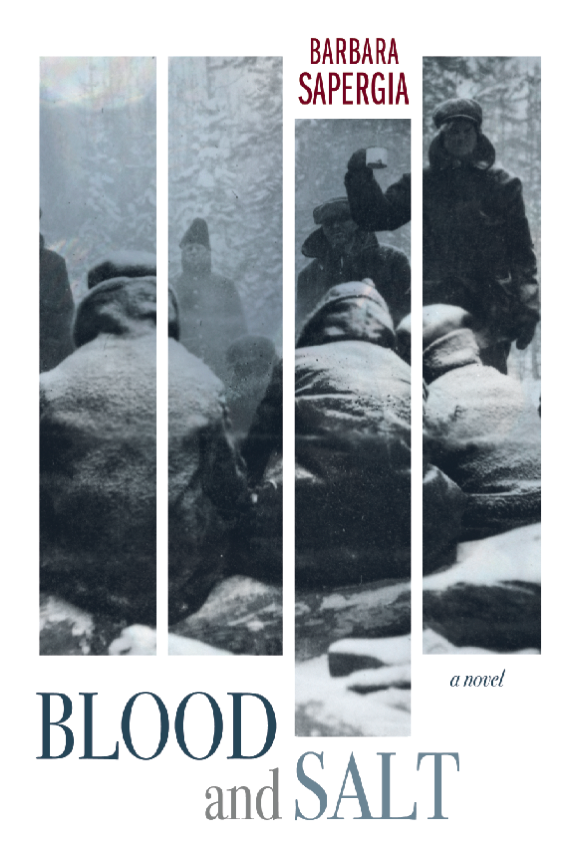

Blood and Salt

Authors: Barbara Sapergia

Tags: #language, #Ukrainian, #saga, #Canada, #Manitoba, #internment camp, #war, #historical fiction, #prejudice, #racism, #storytelling, #horses

- Title Page

- Publication Information

- Dedication

- Part 1

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Part 2

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Part 3

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Part 4

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Part 5

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Part 6

- Chapter 42

- Chapter 43

- Chapter 44

- Chapter 45

- Chapter 46

- Part 7

- Chapter 47

- Acknowledgements

- Photographic Credits

- About the Author

© Barbara Sapergia

,

2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

In this book, names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Edited by Geoffrey Ursell

Cover and text designed by Tania Craan

Typeset by Susan Buck

Printed and bound in Canada

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Sapergia, Barbara,

Blood and salt / Barbara Sapergia.

ISBN 978-1-55050-7-171

I. Title.

PS8587.A375B56 2012 C813'.54 C2012-903823-7

Also issued in print and pdf format.

Print ISBN 9781550505139

PDF ISBN 9781550505351

Available in canada from:

2517 Victoria Avenue

Regina, Saskatchewan

Canada S4P 0T2

Coteau Books gratefully acknowledges the financial support of its publishing program by: the Saskatchewan Arts Board, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the City of Regina Arts Commission. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this book of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

This book is dedicated to the memory of the men, women and children who were interned in Canada during World War I.

PART 1

CHAPTER 1

Going to the moun

tain

August 18, 1915

Taras Kalyna

sits turned to the window. Nothing to see but his reflection. Ashy skin, tangled black hair, eyes staring into the dark. A see-through man. He looks past this ghost to the banks along the track where the train’s lamps cast a faint glow. Ghost land. For all he can tell, the world might end in blackness just beyond the light.

He’s travelling west to a place he’s never heard of. He doesn’t understand how he came to lose his freedom. A week ago he had a job laying bricks to build a school in a small town in southern Saskatchewan. Now it’s as if none of that existed. Like the other men in this car, he’s a Ukrainian immigrant to Canada. He thinks this has something to do with why he’s on this train.

The man beside him, Yaroslav – a railway worker – keeps trying to get him talking. What’s your name?

Taras Kalyna

. Are you married?

No.

Where did you come from in the old country?

Bukovyna.

Bukovyna is part of the Austrian empire. Canada is at war with Austria and Germany. Taras thinks this also has something to do with why he’s on this train.

Yaroslav nods, taking in the news that Taras is from Bukovyna. Yaroslav must be at least forty. Grey strands crowd out the brown in his tangled hair and beard. He’s skinny and the tendons in his neck stick out like ropes. Now he’s talking again.

“They’ve got no right to hold us.” He looks hard at Taras, seems to expect a response.

“No, they’ve got no right.” Taras tries to suck in a deep breath. The hot moist air sticks to him like sweat. He’s young, he doesn’t know anything about rights. He only knows what happened to him.

It doesn’t occur to him that Yaroslav might be trying to help. That he sees a young man who’s angry and confused and might need to talk. Yaroslav tries again, says he’s from the province of Halychyna – what the Canadians call Galicia – near Lviv, a beautiful old city. Has Taras ever been there?

Taras mumbles that he passed through Lviv once, and turns again to the window. He’s not going to say he was running from the Austrian army at the time. Anyway, what’s the point of talking? With somebody who looks like a starving hound. Sure, he must look nearly as bad himself. His crumpled blue shirt sticks to him, his armpits sting. He hasn’t shaved in a week. Nothing to shave with. He’s been sitting in a detention centre in Lethbridge, waiting for the people in charge to decide what to do with him. They put him on this train eight hours ago. It feels like days. Wheels clank against the track and everything gives way to their rhythm. Hard wooden seats dig into his bones.

He keeps asking himself, What have I done wrong? Why am I

here?

He counts about forty prisoners in the car, watched by four soldiers. Two sit at each end, rigid as statues, clutching rifles with bayonets fixed. Somebody must think a bunch of dazed, half-starved men are really dangerous. To hell with the stone-faced bastards.

He looks away from them and in a moment he’s back at the meeting where the police dragged him away.

A meeting to start a union at the brick plant. He never wanted to be there in the first place – only went because his friend Moses asked him to. The local police knew he did nothing wrong, knew he didn’t organize the meeting; he’s sure of that much. In fact he’s pretty sure they didn’t want to arrest him in the first place.

He sees the bare room where they interviewed him, hears the repeated questions. Do you own any firearms?

No, but I snare rabbits sometimes for our supper.

Do you have any contact with the Austrian government?

No, why would I? I left that place.

Just answer the question. Do you belong to any subversive organizations?

I don’t understand.

The policeman explaining what subversive meant.

No, I work at the Spring Creek brick plant, and when I can, I help my parents break their land.

Land which is unsuitable for any kind of farming, he’d wanted to add, but didn’t.

He thinks the local Mounties believed what he said. But they washed their hands of him and shipped him to a detention camp in Lethbridge, Alberta, where he soon saw that he wasn’t the only one arrested. There must have been a hundred other men, most of them as confused as he was.

In Lethbridge it was soldiers who questioned him. Like the Mounties, they asked about subversive organizations. Spying. Sabotage, which apparently meant blowing up bridges, or buildings. They asked their questions over and over, as if they thought he’d been lying and would eventually slip and tell the truth. “No” was always the wrong answer and they kept on asking. Now he’s on this train.

He wonders if there

are

subversive organizations in rural Saskatchewan. Where he would even look to find one.

In the darkness Taras no longer has any sense of forward motion. What if the train’s just rocking in place and never arrives anywhere? Hunger bites his belly. Nothing to eat since Lethbridge. He’s desperate to get off this train but doesn’t want to get where it’s going. They told him he’d be going to an

internment

camp. Taras doesn’t understand the English word, but he thinks it means a kind of prison.

Wheels screech, the car bucks and jolts, and the train enters a curve in the track. The headlamp flashes light on the rails and trees flare into life; darkness swallows them back in a second. Now at least he can feel the forward thrust, his body hurtling into the night.

At the sun’s last light he thought he could make out giant shapes against the sky. But maybe he only imagined them because a soldier at the detention centre said he’d be going to the mountains.

“You’ll work. But you’ll be taken care of.”

The soldier wouldn’t look him in the eye.

He’s never seen mountains, but he thinks he can feel them out there. Looming, dark shapes just outside the window, cutting off light.

Half an hour

ago the guards agreed the windows could be opened.

“Christ,”

Yaroslav said to the nearest guards, “do you think we’re gonna jump out the window? Off a goddamn moving train?”

“Watch your language,” said a private, gripping his rifle stock so tight his knuckles went white.

“I suppose not,” said the sergeant.

“Not yet, anyway,” somebody muttered, but the sergeant had the private open one window and the prisoners did the rest.

Taras can’t feel

much difference. Too hot outside. And the train moves too slowly to create any real breeze. He fingers the back of his seat, scored with the names of people coming to the west. This could even be the same Colonist car that carried him and his parents across Canada to Saskatchewan. He remembers the noise and the clamour of many languages, and the bread and cheese Batko bought along the way. Mama amazed at the idea of

buying

bread. This all happened not much more than a year ago. A few months before the war began.