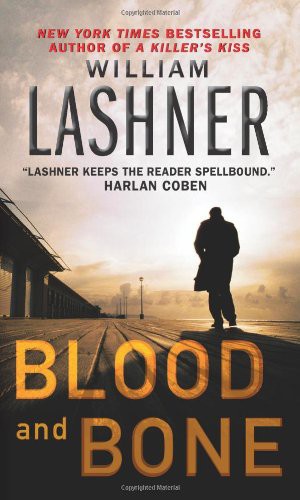

Blood and Bone

BLOOD

WILLIAM LASHNER

To my dad,

To my dad,

who is with me every day

Why might not that be the skull of a lawyer? Where be his quiddits now, his quillets, his cases, his tenures, and his tricks?

—Hamlet, in the graveyard, act 5, scene 1

Contents

Epigraph

iii

KYLE, ALL OF TWELVE years old, hated the suit. 1

THE NAME WAS ROBERT, not Bobby or little Bobby or… 15

KYLE BYRNE SPIED his father watching him play in the… 25

OH, MY GOD, it was the funniest damn thing I… 32

AS HE WALKED east down Lombard, he saw her sitting… 40

BUBBA’S BAR AND GRILL, just a few blocks away from… 44

NICE DAY FOR A FUNERAL,” said Detective Ramirez. 50

IF KYLE BYRNE collected comic books, Laszlo Toth’s

funeral would… 58

ROBERT SPANGLER WAS LISTENING to a priest drone on at… 65

THE OLDE PIG SNOUT TAVERN in South Philly was as… 71

LIAM BYRNE HAD BEEN many things: faithless lover,

indifferent father,… 79

ROBERT SPANGLER SAT low in his car in the alleyway… 85 SKITCH WAS DRUNK. You could tell by the way he… 88

DETECTIVES HENDERSON AND RAMIREZ stood side by side in front… 96

RAMIREZ SAT DOWN across from Kyle Byrne. His eyes were… 101

ACROSS THE STREET from the Snow White Diner, on the… 110

LASZLO TOTH MIGHT HAVE BEEN the ogre in Kyle Byrne’s… 115

KYLE’S CAR WAS an old red Datsun 280ZX, with a… 118

WHO THE HELL are you?” rasped the small man with… 125

HENDERSON AND RAMIREZ were at a crime scene when they… 134

DETECTIVE RAMIREZ FELT a slight but undeniable thrill as she… 138

ROBERT BOUGHT the prepaid cell phone at a Wawa convenience… 147

ROBERT HAD PICKED the spot long before the call came… 152

KYLE BYRNE WAS PISSED. He was a little drunk, too,… 159

THE DISCUSSION DID NOT go very well. 166

IN THE COVER of darkness, Kyle parked the 280ZX at… 169 IT DIDN’T TAKE much time for Kyle to clear out… 174

THERE HADN’T BEEN enough time to make elaborate

provisions, but… 181

KYLE’S HEART JUMPED like a nervous rabbit flushed from hiding… 186

OR SOMETHING THAT sounded much like a bomb, an explosion… 191

DAWN WAS JUST BREAKING as Henderson and

Ramirez toured the… 198

A MOTEL ROOM IS where romance goes to die. 207

IT BEGAN WITH A MEETING in his office. An older… 211

FOR THE FIRST TIME in his life, Bobby Spangler’s world… 218

BEFORE WE DO ANYTHING,” said Liam Byrne as they drove… 223

WATCH OUT FOR THE SUIT,” said Kyle as Vern and… 232

DETECTIVE RAMIREZ FIGURED it wouldn’t be much of a trick… 237

WELCOME TO SENATOR TRUSCOTT’S Philadelphia office,” said the pretty receptionist… 245

HIS NAME WAS Lamar, and Lamar was scared. 252 AT PONZIO’S, an overblown New Jersey diner with a false… 259

SKITCH SAT WITH KYLE in Liam’s rental car as both… 266

DID YOU SEE his face, boyo?” said Liam Byrne, peering… 271

BOBBY HATED BLOOD. 281

KNOCK, KNOCK. 285

A SENATOR WALKS INTO A BAR. 294

ONE OF MY GREAT-GRANDFATHERS was a crony of

Morgan’s,” said… 300

AS KYLE WATCHED Truscott drag himself out of

Bubba’s, looking… 309

EVEN WITH HIS BLACK BAG on the passenger seat beside… 313

AFTER DETECTIVE RAMIREZ yanked Kyle Byrne back into Bubba’s, she… 318

UNCLE MAX WAS SITTING at the bar of the Olde… 327

KYLE BYRNE WAS drunk with whine. 335

BOBBY DRAGGED THE BLACK SATCHEL through the

rhododendron, bony stalks… 340

I FEEL LIKE THERE ARE ANTS crawling across my chest,”… 344

BOBBY PEEKED OVER the hedge and saw the Byrne boy… 349

THE HOUSE KYLE BYRNE found himself inside smelled

ancient, dank,… 352

THERE WAS A TIME, during his youth in Iowa, when… 359

LATER DETECTIVE RAMIREZ would squat beside the

bloodied body and… 369

IN THE MIDDLE of the night, lying awake in the… 377

SHE WASN’T DETECTIVE RAMIREZ on this night,

she was Lucia,… 381

About the Author

Other Books by William Lashner

Credits

Cover

Copyright

About the Publisher

1994

KYLE, ALL OF TWELVE years old, hated the suit.

He hated everything else about this day, too—his Uncle Max’s voice droning on from the driver’s seat of the battered black pickup, the bright sun shining into his eyes, the way the truck was filled with smoke from his mother’s cigarette, the expectant dread that twisted his stomach. But most of all he hated the suit.

His mother had bought it for him just yesterday, snatched it off the rack at some discount warehouse and held it up for him, limp and gray, as if it were some dead animal she had shot and dragged home. “For tomorrow,” she said with that same detached smile she had been wearing ever since he came home from school, backpack still on his shoulder, and she told him the news.

“I don’t want to wear a suit,” he said.

“I bought it big,” she said, ignoring his declaration, “so you could have it for next year, too.”

And now there it was, wrapped around his body like a fist, his first suit. It didn’t fit right; the pants were too long, the shoulders too narrow, the tie choked him. He wondered how anyone could wear such an uncomfortable thing every day. Especially the tie. His father always had one slung around his neck whenever he came for a visit. Navy blue suit, dark thin tie, yellow-toothed smile and shock of white hair. “Hello, boyo,” he’d say whenever he saw Kyle, giving his hair a quick tousle.

“I never liked the son of a bitch,” said Uncle Max. Uncle Max was Kyle’s mother’s older brother. He had come out from the city for the funeral, which was a treat in itself. Not.

“Stop it, Max,” said Kyle’s mother.

“I’m just saying.”

“You’ve been saying for twelve years.”

“And I’ve been right all along, haven’t I?” Uncle Max wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “Where was he anyway when he got it?”

“New Jersey.”

“What, he had someone stashed there, too?”

“Quiet.”

“Yeah, yeah. Okay. But we’re better off without him, all of us. What did Laszlo say it was?”

“Heart.”

“Figures. Is he saving us a place or something?”

Kyle’s mother didn’t answer. She just inhaled from her cigarette and leaned her head against the window.

“Let me guess. You wasn’t even invited.”

“Laszlo suggested that it might be best if we didn’t come.”

“Well, then,” said Uncle Max, “this might be more fun than I thought.”

Kyle, wedged in the front seat between his uncle and his mother, craned his neck and shaded his eyes as he peered through the windshield. In the sky a dark cloud kept pace with the car. Kyle was missing school today, which was good, but he had a game that afternoon, and he’d probably have to miss that, too, which sucked. And then he hadn’t cried yet, which only confirmed what he had always believed, that there was something seriously wrong with him. His mother hadn’t cried either, as far as he could tell. She had her strange smile, like in that painting of that Mona lady, and she was smoking, nonstop, which was a sign of something, but Kyle had seen no tears from her. And Uncle Max certainly didn’t seem so cut up about the whole thing. So maybe it wasn’t such a deal after all. Except in the soft, untrammeled depths of his heart, he knew that it was, knew that it was bigger than everything and that he should be bawling his eyes out and that there was something seriously wrong with him because he wasn’t.

The neat little houses passing by gave way to a low stone wall. Beyond the wall were gravestones and small marble crypts like out of

Scooby-Doo

. The quick change in scenery jolted Kyle back to the unpleasant task at hand. He stuck his thumb into his collar at the front of his neck and yanked it down. It didn’t help.

Uncle Max turned the truck into the cemetery. There was a chapel off to the right, like one of the crypts, only large enough to inter an army of ghouls.

“Showtime,” said Uncle Max as he pulled into one of the remaining spots in the parking lot and killed the engine.

A thin crowd of mourners milled somberly at the entrance as the three approached. They walked side by side by side—Uncle Max, thick-shouldered and in a loud sport coat; Kyle’s mother, tall and drawn in a long black dress; and Kyle, in his ill-fitting gray suit. A few faces turned toward them, and the crowd suddenly stilled, as if they were a trio of gunfighters walking down a dusty street in a black-andwhite western on TV. Kyle hesitated for a moment, but his mother raised her chin and kept on walking as though she hadn’t noticed the stares. Kyle hitched his pants and caught up.

On the wall of the chapel, behind a sheet of glass and pressed into a black background, was a series of white plastic letters.

FUNERAL OF LIA M BYRNE 10 :30

MAY GOD GRANT PEACE UNTO HIS SOUL

“Fat chance of that,” said Uncle Max under his breath as he held open the heavy metal door.

Kyle stepped through the doorway into the cool, dark interior. The chapel was built of stone, with rows of dark wooden pews, most already filled. Sunlight slipped through a stained-glass image of sunlight slipping through clouds. A line of people snaked through the middle aisle toward a heavy table in front. Faces from the pews turned to look at the three of them, a few did double takes. Kyle’s mother stepped confidently forward and sat in one of the rear pews. Kyle slid in next to her. Uncle Max dropped down heavily beside him.

“Everyone is looking at us funny,” said Kyle.

“Let ’em, the sons of bitches,” said Uncle Max loudly.

Someone shushed him. Uncle Max made a face.

“You should go on up and touch the urn,” said Kyle’s mother to Kyle.

“Why isn’t there a coffin?”

“I guess he wanted to be cremated.”

“So that’s all that’s left?”

“Go on up.”

“I don’t want to.”

“You need to say good-bye.”

“What about you?”

“I said good-bye already. Go on.”

There was more behind the request than mere politeness; it was like she knew everything—how he felt now, scared and yet cold and distant from all this, and how the future would play out for him because of it. His mother was never one to be lightly ignored, so Kyle rose slowly from his seat, climbed past Uncle Max, and sheepishly made his way to the back of the line.

It moved slowly, in fits and starts. People fell in behind Kyle, talking in hushed voices, important-looking people who had taken time out of their important days to honor what was left in the urn. Kyle stared at a man in a dark suit standing by the table. His shoulders were broad, his hands clasped before him. Kyle wondered if he was Secret Service or something because of the way he stood, but why would the Secret Service be in this crappy little chapel? The woman in front of Kyle stepped to the left, and suddenly there it was.

Two huge bouquets of flowers surrounding a funeral urn, shiny and blue, its body covered in grasping green vines and tiny white flowers. The urn was shaped like a squat man about the size of a football, flaring wide in his shoulders with just a tiny head. When Kyle saw it there, he stepped back involuntarily, bumping into the man behind him.

The man gently pushed him forward. “Go ahead, son,” he said.

Kyle hesitated for a moment. He liked the warmth of the man’s hands on his shoulders, the reassuring sound of his voice. “Son,” he had called him. Yeah, right. Kyle took a step forward, reached out to touch the urn as his mother had instructed, when he was blocked by a large hand sticking out of a dark-suited arm.

“No touching,” said the man standing guard.

“My mom told me I should—”

“There’s no touching.”

“But,” said Kyle, “. . . but it’s—”

“Keep moving,” said the man, as if he were a cop at an accident.

Keep moving, nothing to see here. Just some useless ashes in a stinking pot

. The man directed Kyle to the left, where the line bent toward a row of people sitting in the front pew. Kyle stared at the man for a moment, looking for the earpiece he knew from television that all Secret Service agents wore. Not there, he wouldn’t go to jail if he ignored him, but it didn’t seem like the smartest idea just then, so he nodded and turned away.

Those in the line were giving their condolences, one by one, to the faces in the front pew, taking the proffered hands between their own and offering tender words of commiseration.

I’m so sorry for your loss. We will all miss him. He was a terrific lawyer and a better person. So, so sorry

. It made Kyle sad and angry both, all these people offering their condolences. Who were those getting comforted? Why weren’t they comforting him?

He didn’t want to be here anymore. On the far wall was a door, and he thought of escaping through it, out of the chapel, into the sunlight. Maybe if he started running now and kept on going, he could get to the police field in time for the game. Would they let him pitch in the suit? He was about to head right for the door when he noticed the red emergency-exit bar signaling an alarm if it was opened. He felt trapped, like a gray-suited badger in a cage, as he was pushed forward with the line.

A small, hunched man with slicked-back black hair and lidded eyes was standing at the head of the pew. He tilted his head at Kyle and attempted something like a kind smile. The man reached out a hand and took Kyle’s in his own, forcing an awkward shake. “Thank you for coming,” he said quietly.

“Sure,” said Kyle.

“And what would be your name, young man?”

“Kyle,” said Kyle, and suddenly the man’s kind smile became a little less kind. Still gripping Kyle’s hand, he turned his hunched back as best he could and craned his neck to peer behind him. Craned his neck until he spotted Kyle’s mother. Then he gestured to the man in the dark suit standing by the urn.

As the man started over, the hunched little man gripped Kyle’s hand even tighter and said in a soft, insistent voice, “You should go now, Kyle. The nice man over there will help you find your way out.”

“Who is this, Laszlo?” said a woman seated next to him, an older woman with large dark glasses and styled black hair. She spoke in some sort of accent. Like Pepé Le Pew.

“It’s just a boy,” said Laszlo.

“Give your hand to me, young man,” she said. Laszlo reluctantly let go of Kyle’s hand, and the woman took hold of it in one gentle hand as she patted it with the other. Her lips were bright red and puffy; she smelled of some ferocious perfume that was vaguely familiar. “Thank you so for coming today,” she said. “Did you perhaps know my husband?”

“Who is your husband?” said Kyle.

“How darling,” she said. “He does not know. My husband was Liam Byrne. It is his funeral service today.”

“Let the boy move on,” said Laszlo.

“He came to pay his respects,” said the woman. “He is a sweetlooking boy. Tell me, young man, did you know my husband?”

“Sort of,” said Kyle. “He was my father.”

It was her lips that he noticed most of all, the way the bright red slabs of flesh tensed and froze at his words before opening up in soft sympathy. He couldn’t take his eyes off them; they seemed unaccountably beautiful. He stared at the woman’s lips even as she lifted her hand and placed it on Kyle’s cheek.

“So you are the one,” she said. “My poor boy.”

Her hand felt warm as it lay against his flesh, and strangely consoling. He leaned his head into it, as if this were the touch of sympathy he had been waiting for since he heard the news.

“My poor, poor boy.”

Her flesh was so warm and comforting that it took him a moment to recognize the growing locus of pain beneath her touch for what it was. The old bat was pinching his cheek. And as she did, her lovely red lips tightened and twitched.

“You shouldn’t have to suffer through this.”

The pinching grew harder and the pain so severe he tried to step away, but her grip on his skin was excruciatingly tight and he was unable to pull free.

“A boy like you has no place here,” she said. “You can only pollute the remembrances. Laszlo, take this boy away, now, before this sad day becomes too painful for him to bear.”