Blessed Isle (5 page)

Authors: Alex Beecroft

McCall’s fatal tumble from the rigging had made my mind up. No matter our determination, we could not sail directly into the wind. We would have to dare the Horn. I would give the order to turn west the moment Garnet returned.

Driving rain had begun to lash horizontally across the greasy grey swells of the building sea. Garnet’s body, as he scrambled aboard, made a hole in this wall of water. His lips were blue, and beneath his sable hat, his hair whipped forward, thrashing like black tentacles. The pupils of his eyes were wide and dark as if from opium smoke. “They’re dead,” he said. “They’re all dead.”

“Get a grip, man!” I exclaimed, twisted within at his distress. But I needed him back, under control and at work, more than I needed to give sympathy. “What the hell kind of a report is that?”

As soon as I got the true story out of him, I roused our own invalids on deck. We fought our way to the limping hulks of the transports, grappling and pulling them close one by one. The poor remnants of the crew from

Drake

and

Cornwall

amounted to no more than ten exhausted men bent double against the strengthening wind, speechless and cadaverous and dappled with livid red spots. I would not abandon even the violent convicts, much less those whose crimes had been merely to be hungry and desperate, and so as the waves mounted I sent the marines to swarm across from one ship to the next, breaking open the barred doors and bringing every human creature who still drew breath into the

Banshee

.

Lashed together with

Quicksilver

, we plummeted down the troughs of waves that had become mountainsides. The sky had met the sea, and we breathed water only a little less dense than the ocean. The tear and smack and boom of lightning raced towards us on clouds like boiling black tar.

Banshee

wailed like her namesake as the unmanned

Quicksilver

wrenched at her, turning her broadside into waves that smashed down upon her like rockslides. I grabbed the arm of the last convict, scraped him over the rail, dropped him on the deck and hacked at the cables holding the dead ship to our living one. They parted, and as I screamed orders to set

Banshee

running before the wind, I saw the three abandoned vessels of my little fleet heel over, the sea swamping aboard them. A wallow, a moment’s smoothness on the surface of that raging ocean, and they were gone.

Happy the man who dies in the middle of a storm—who never reaches the safety and sanctuary of calm, who never has time to contemplate the ruin he has just suffered. For there was my career and my reputation gone in under a minute, and if I’d had time to think about it then, I might not have had courage for what was to come.

But the wind veered and hauled about us, and the wheel bucked beneath the helmsman’s hands like an unbroken stallion. Lightning hit the water next to us in a bang and a plume of steam, lanced down again, and we heard a shriek like the gates of hell opening, saw one intense, vivid image of the supply ship,

Ardent

, lit up, dazzling white against the black abyss of sky and sea as the bolt hit her main mast. Everything blazed, etched in burning bright lines and fathomless dark. And then she was behind us too, a suggestion of flame in the gloom.

Michael Franklin at the wheel gave a highpitched, gurgling scream. He must briefly have let go. The wheel had spun and the spokes caught him in the stomach, beneath the ribs. I don’t know whether he still lived at that point. It was grab him or grab the helm, and to let the wheel spin was to risk every soul aboard. His body tumbled past me as I crawled, bent double against the wind, to reach the helm. The wheel almost lifted me from the deck. I clung on, every muscle in my back and belly tearing with the effort of holding it still, fighting the pull of the sea, the insolent, easy strength of the wind.

It blew for nine days.

I remember very little of the end of it. Hands, on mine, eased my claw-like grip off the spokes. I recall my puzzlement as to what this warmth could be about my fingers. Looking up, I saw a face where I had been used to seeing the sky. “Sir,” this face said, “it’s safe for you to sleep now. Come on.”

It was Garnet, of course.

I had been somewhere far away from humanity, from speech and thought and regret. As he got a shoulder under my arm and peeled me from the helm, I felt my senses were being darkened—I had become the ship. I had forgotten what it was to be a man.

“Come now.” He taught me to walk again, guiding my uncertain steps into the cabin. “It’s over and we’re through it. Go to sleep, sir.”

Between the two of us—I daresay I was very little help—I was tumbled into my cot and covered with blankets. As I spiralled into unconsciousness he leaned over and kissed my brow, his lips like sandpaper and his hollow cheeks furred with ten days’ growth of beard.

When I woke, a day later, I had stiffened in every limb. I shuffled, bleary-eyed, out of the cabin, wondering what a captain had to do to get a cup of coffee and a hot breakfast after he had steered his ship single-handedly through the storm.

A pearl-grey sky floated above us, wisps of cloud hurrying from the east. The foremast lay over the bow in a cat’s cradle of fallen rigging, dragging at us like a sea anchor. Why was no one attending to it?

Zachary Walsh stood asleep at the wheel, and on all the rigging and the rails of the ship drowsed hundreds of sea birds exhausted by the storm. We were covered over with bundles of white feathers, but there was no other human being on deck.

“Zachary! Zach!” I whispered, my voice as stiff and overstrained as my muscles. As I reached out to shake him awake, his head tilted gently with the roll of the ship and I saw the hectic flush, the red rash of typhus that spread beneath his chin. Casting a hitch about the wheel to keep us on course, I caught him before he fell and hauled him laboriously to the companionway stair.

“Lieutenant Kent! Dr Mortimer!” I called, trying not to let the panic enter my voice. “Where the hell is everyone?”

The answer met me on the gun deck: long rows of swathed shapes, and a shorter row of invalids hanging in their hammocks. Someone had opened three of the gunports and a wet, cold breeze blew in, making the stench endurable. I like to think my first thought was not

Not Garnet— please say he is still alive!

But that thought was very present, adding a newly personal twist to my feeling of helplessly falling.

A sound of knocking came up from the orlop deck beneath my feet—metal on wood, the clatter and glissade of chains. I will admit my skin crawled. I thought myself dead, the captain of a ghost ship condemned to sail these bitter waters for all time as a warning against . . .

But there my imagination faltered, and the door to the wardroom opened, proving me not quite abandoned yet. Garnet came out, with a kind of calmness in his demeanour that spoke of having endured madness and won through it, sailing shattered out the other side. He had even shaved.

He had even shaved! I could have kissed him for that act of defiance, of humanity in the face of this utter ruin. But Mortimer came out after him and so I did not.

“Captain,” Garnet said gently, and took hold of Zach’s trailing legs by the knees. Together we manoeuvred the man into a waiting hammock. Garnet turned aside to find a blanket, tucked it in around the unconscious sailor with a fatherly tenderness I had not anticipated in him. He was so reassuringly in control of himself that I found it easy to imitate him—to click back into place like the rudder sliding back onto its pintles, ready for use. Affection for him swelled up and almost filled the hollow place the state of my ship had opened in my chest.

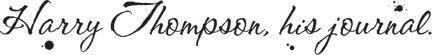

“This happened during the storm?” I asked, nodding at the line of casualties without taking my eyes from the edge of his lips. He had a little scar there. Perhaps he’d split it, fighting as a child. It glimmered silver. I thought the skin must be thinner than in other places, the pulse beneath hotter, and at the thought life came thundering back into my veins, scalding sweet. I regretted the dead—their names are in the beginning of this book and I read them over every night—but the same life that breaks the shell, that sends the sap of trees hammering into the sky, demanded its recognition from me. We were not dead, either of us. We were alive, and I ached to prove it.

Garnet responded to my gaze. His nostrils flared and his mouth opened a little. He inched forward. If we had been alone I believe we would have rutted there amidst the corpses, and it would have been . . . It would have been holy, in some way: life’s victory, an affirmation that love was greater than death.

But we were not alone. Garnet wrenched himself away, cleared his throat. I sat down shakily on the nearest cannon. And Dr Mortimer, who looked like the skin of a sausage after the meat has been squeezed out, said, “I’ve no doubt the disease has been aboard some time, manifesting itself only as a general malaise and lowness of spirits. But the storm taxed our resistance too greatly. We could no longer keep it in check, and it has spread—” his smile, even now, was not without an element of scientific interest “—with extraordinary rapidity and completeness.”

“So I see.” I stood, lifting up along with my bones the weight of responsibility for all of this. “There is no one on deck. How many men do we have fit for duty?”

“Six.” Mortimer did not attempt to soften the blow. “The three of us. Lieutenant Gregory, the commander of the

Quicksilver

. Taff Walsh, foretopman out of the

Cornwall

. And Ben Hough, one of the jailers, also out of the

Cornwall

. They are asleep, but I can rouse them if you wish.”

“No, let them rest. I’ve no doubt they need it.” “If, under Providence,” Mortimer went on with a careful note of hope, “we are permitted another week of calm, then I believe I should be able to provide you with a further nineteen convalescents, capable of light duties.”

“Very well,” I said, quailing inside. Six exhausted men to handle a three-masted ship as she negotiated her way into an unknown harbour in potentially foul winds? Yet we could not stay at sea. Not here in this perilous southern ocean, where storms came as regular as the tick of a clock.

As I thought this, there came again that deep, indistinct groaning from the hollow of the hold beneath us—the rattle of chains and something that sounded almost like speech. My wits had settled and this time, though the hair still stood up on my arms, I took a lantern from its nail in the bulkhead and edged slowly down the ladder. The noise stilled. The light ran away from me, illuminating the ribs of the hull like the belly of a whale and revealing blackened, shabby, hunched things that moved, shuffling forward until their chains twanged taut. Their eyes glistened with the flame of my lamp.

“Get us out of here!” He was a flash of teeth in a tangled beard. A distinguished-looking man once, perhaps, but goblin-like in that half-light. I’ve never seen eyes before or since that had such a red light in them, but his words were reasoned enough. “Please, Captain! You are the captain, ain’t you? Please, we can help! Just let us out.”

“You’ve been fed?” I asked, while inside, my heart seemed to turn to brass, its beat jerky and far more terrified than it had ever been facing the French.

“Oh aye,” said he. “And watered like cattle when they could spare the time. But we’ve all had the fever, ain’t we, and come out the other side, fit and healthy, and you need us.”

I didn’t like his smile. The records of his offence had gone down with his ship, but if he had not done murder in the past, I believed he was contemplating it now.

“I will think on it,” I said, and went out into the open air with the sense that I was running away.

“There are three-and-twenty of them, sir.” Garnet had followed me, and now he leaned into the wheel for support. “Twenty-three men, with nothing to look forward to at our destination but dust and chains. And six of us. If there’s a single man among them with knowledge of navigation, we’d be signing our death warrant to let them free.”

I took a glass and climbed to the mainmast topmast yard, scouring the three hundred and sixty degrees of horizon for land. Given nine days running before a wind of twelve knots or more, we must have rounded the Horn in the storm. America should lie to the east—the long hospitable coast of Chile, where we could land and nurse our invalids back to life, rest and eat and regain our strength, and draft in any adventurous Chilean lad who cared to sail with us. If there was but a blue, cloudlike shape on the edge of sight, a change in sea and clouds, we might yet be saved.