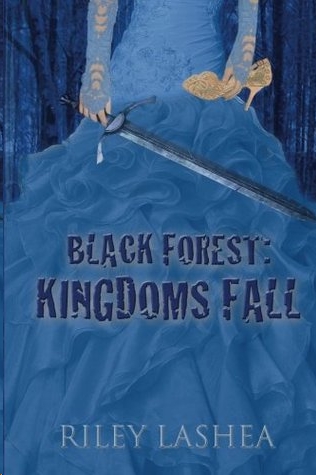

Black Forest: Kingdoms Fall

If this book feels familiar, it should.

Black Forest: Kingdoms Fall

is a reimagining of my 2005 novel

Bleeding Through Kingdoms: Cinderella's Rebellion

. This will be the only time that, as an author, I allow myself to go back and redo a work I have already released, but I am glad I did.

O

nce upon a time, there was a library on a hill, where the shelves filled with more madness than words. It was attached to a cottage, but the living space

was crammed into the room left over, an afterthought to the books, the hand-carved writing desk, freshly-plucked quills, yellowing parchments, and oozing

black inks.

The man who lived there had hair and eyes as black as the deepest night, and all his time spent indoors, hiding from the sun, hiding from the world, his

skin was as translucent as gauze. He sacrificed little of his life to the spaces beyond the library, sleeping in spurts and forgetting to eat, so he was

nearly as thin as the books he wrote.

His were powerful hands. He had discovered it as a boy. With his hands, he could give birth to life. Manipulate, destroy and resurrect it. Pleasure and

torture thrived at his hands' command. The power they possessed, it was stronger than the universe itself.

His hands would create his immortality. Through his work, the man knew, he would live forever.

It was on a night of temperamental weather, sleet and hail taking turns raking against the windows, so loud they pulled him from his short burst of sleep,

that the dark man lifted his head from his desk, where he had proven more prone to sleep in recent weeks than his bed, and walked to the library's center.

There stood a glass case, so reverently regarded it had the air of a sarcophagus.

This was where She lived. She was the one, the one for whom he would be most revered. Her name would be spoken in every land. In every tongue.

On every

tongue.

Sliding the heavy silver key he never let leave his neck into the lock, the man stilled for a moment, regarding the work. This would be the last of it, his

final chapters, a happy ending for his greatest creation. She had been through Her most brutal trial. By fire indeed, he thought with a smile. Now, She was

simply waiting for him, waiting for the happy ending promised to all his beloved characters.

Twisting the key, the man lifted the glass lid and pulled the leather-bound story from within, cradling it against his chest like a child. Desk clear but

for his tools, he sat the tome gently before him and eased back the ribbon to the page on which he last left Her.

Jarring sight pulling him instantly from the relaxed state into which drink had put him, the man thought with a nervous laugh he must have been overly

tired when he quit work on Her story the night before. There was no other explanation for the steps of the palace to be empty where the prince had stood,

no reason for The Girl to be gone from where She was in the process of fleeing.

Turning back a page, the man's heart calmed when he saw Her standing there, anxious green eyes raised to the clock as it struck midnight.

Flipping again to the page that demanded his attention, the man steadied his hand before picking up the quill and dipping into ebony ink. With assured

strokes, he began the outline, watching the prince take form on the page. He would stand at Her back, calling for Her to stay. Perhaps, it would not be the

same as the night before. Perhaps, it would be better.

Dipping the quill into the bowl of water, he wiped the tip clean, and gathered more black ink. Quill pausing over the parchment, he took great care in

laying down the first stroke, shaping the contour of Her head just so, before lifting the quill to admire the delicate curve of Her face.

It was better, he thought.

Line fading, the man frowned, watching the ink lose its pigment, turning gray on the page until it disappeared completely. Pressing the quill back to the

paper with greater force, the tip threatened the parchment as he retraced the curve, only to watch it again disappear, evaporating as if it was no more

than a water spot.

Moving to a new position, he began an arm, long line imperfect as his hand shook upon the quill. Before he reached the end of one thin wrist, the top of

Her arm faded once more.

Dipping desperately into ebony, the man dragged his hand across the page, ink falling without order upon the scene. The blots remained as they fell, but

The Girl refused. Each time his hand attempted to put Her on the page - head, arm, hip, gold-clad foot - She vanished before him, as if She never existed.

Try and try again, the man fought the page until the sleet against the roof drove him to the edge of his mind, but no matter what he tried, words or image

of Her, he could not get Her back.

His greatest creation had vanished.

The Maiden Awakens

W

ater ran warm in the halls of the palace, a perk of servitude that, in months of cool winds, made even the freest of peasants long for captivity. Those

who lived within the walls were not sheltered at their wishes, though, but at those of the king, who had them plucked from the stalls and barns and

sanctuaries of the village as they appealed to him.

Like the others, Akasha was also different. She too had been chosen, but at her own will, having placed herself in the king's path after she abandoned hope

of any other life. Her parents had encouraged the decision, their concerns that she would never be matched, that they feared for her a lonely life, guiding

her.

Beautiful enough for a king, too ugly for a peasant, Akasha adopted their fears as her own. Harem girls turned servant, her parents told her. Chosen by the

king, she would spend her whole life in the palace. She would never go hungry or cold. Taken in half a decade before, a single cycle of the moon before the

most brutal storm ever to hit Naxos scaled the town walls, the palace saved her from the flooding that killed half the village, including her parents. It

was then Akasha realized she would also never die a peasant's death.

Turning to pour the contents of the bucket into the waiting bath, Akasha screamed as a face appeared beneath the water. Bucket slipping from her hand, she

stumbled backward, water splashing across the stone floor, as the face emerged, gasping for air. Behind Akasha, girls gathered, anxious for the chance to

see something interesting for the first time in days.

At the sound of the sentry, most rushed away again, settling back into lethargy, trying to look as if they hadn't seen a thing. Those who understood the

danger, whom Akasha could call friends, remained with her, providing cover by pretending to discuss the finer points of bathing.

Putting a hand to the emerging girl's hair, presently a ratty mop atop her head, Akasha pushed her down. "Shhh," she said when the girl would like to have

struggled, succeeding in settling her to just above the level of the water and turning to feign innocence as her friends parted before her.

"What happened here?" the sentry asked.

"I am sorry," Akasha replied, stepping forward. "The bucket, it slipped from my hands."

"All right, let us see then," the sentry said, taking a step forward.

Around the room, Akasha knew, there were girls a breath away from telling the sentry what they had seen. There was always a rush to tattle within the

harem, to stem any punishment that might land upon observers for the crime of silence.

Coming only as far as the bucket, the sentry grabbed it from the floor. "Hm," he said, examining its edge. "Splintered."

The word, so simple, seized Akasha's breath. Her own eyes had seen nothing, but arguing the fact was not merely pointless. To argue it to a member of the

king's guard was mutinous, and mutiny was punishable by death.

Or worse.

From the side of her eye, Akasha saw the eunuch stand, carefully watching, and willed him to sit, as with a nod to the matron the sentry stepped aside and

the matron took his place, gaze sympathetic as it captured Akasha's own. "Hold out your hand." The matron's compassion was kept purposely from her voice.

Doing as she was ordered, producing the hand palm-up, Akasha stared at the matron's shoulder, refusing to flinch at the sound of the whip pulling free of

her belt.

Leather cracking, the matron delivered one lash against Akasha's palm, painful, but only just.

"Harder," the sentry commanded, and the second lash opened skin, forcing a pained breath over Akasha's lips.

"Harder," the sentry said again, and with the third lash, Akasha cried out, eyes falling shut at the burn of her flesh splitting fully.

Whether it was the sight or sound that appeased him, the sentry was clearly satisfied as he shoved the matron aside and towered over Akasha once more.

"This does not belong to you." He brandished the bucket as if it was gold. "It belongs to your Royal Highnesses. Next time, you will be more careful, yes?"

"Yes," Akasha responded, teeth clenched in pain.

"And if you do have an accident," he continued, "you will hold your tongue, or I will give you good reason to scream." Turning, he thrust the bucket at the

matron, causing her to expel a rush of air as it hit her protruding stomach with more force than necessary. "Keep them more in line, or there will be no

use for you here."

Assured steps carrying him back to the door, the sentry passed the eunuch, whose eyes turned to Akasha, awash with too much concern. With a small shake of

her head, she warned him away, and the eunuch sat back down in his corner, gaze returning to the air before him, where he stared, as was his way, at

nothingness.

Glancing past Akasha to the bath, and the girl within it, the matron was curious, but not curious enough to involve herself in anything else that might

bring punishment upon her. As the wise woman walked away, a swarm of younger, less pragmatic girls, more interested in entertainment than security,

gathered back around as Akasha turned to the bathtub, tucking her uninjured hand beneath the newcomer's back to help her sit.

"Who are you?" she asked, but, looking about in confusion, the girl did not seem to possess the answer.

Eyes finally finding focus on Akasha's hand, her face fell in sympathy. "Look at what he did to you," she said, her voice somewhat unusual, a lilt to her

speech Akasha had never heard.

"It is nothing," Akasha replied, dipping her hand into the water, biting back the cry that tried to escape as pink swirled into it. "Come now. Come out of

there."

Responding at once to the order, the girl rose to her knees and stepped over the side. Once out, she just kept coming, the dress she wore so wide and

ornate, it was a wonder it fit into the tub at all. A gown, indigo her mother would have called it, as fancy as any Akasha had ever seen. The girl looked

much like a drowned royal, but no royal Akasha had ever laid eyes upon.