Between the Lines (2 page)

Authors: Jodi Picoult,Samantha van Leer

I was on a book tour in Los Angeles when my telephone rang. “Mom,” my daughter, Sammy, said. “I think I have a pretty good idea for a book.”

This was not extraordinary. Of my three children, Sammy has always been the one with an imagination that is unparalleled. When other kids were playing “stuffed animals,” Sammy would scatter her toys around the house and create elaborate scenarios—this teddy bear is wounded and stuck on top of Mt. Everest and needs a rescue dog to climb to the top and save him. In second grade, her teacher called me to ask if I’d type up Sammy’s short story. Apparently, it was forty pages long. He sent it home with my daughter, and I fully expected a rambling stream of words—instead, I wound up reading a very cohesive story about a duck and a fish that meet on a pond and become best friends. The duck invites the fish to dinner and the fish says he’d love to come. But then the fish has second thoughts:

What if I am dinner?

That, ladies and gentlemen, is called CONFLICT, and it’s the one thing you can’t teach. You are either born a storyteller or not, and my daughter—at age seven—seemed to have an intrinsic sense of how to craft literary tension. Sammy’s creativity continued to blossom as she grew up. Her nightmares are so vivid they’d give Stephen King a run for his money. As a teenager, she has written poetry that made me hunt down my own poetry journals from way back when—only to realize she is a much better writer than I ever was at that age.

So… when Sammy told me she had an interesting idea for a YA book, I listened carefully.

And you know what? She was right.

What if the characters in a book had lives of their own after the cover was closed? What if the act of reading was just these characters performing a play, over and over… but those characters still had dreams, hopes, wishes, and aspirations beyond the roles they acted out on a daily basis for the reader? And what if one of those characters desperately wanted get out of his book?

Better yet, what if one of his readers fell in love with him and decided to help?

“Mom,” Sammy said as I languished in Los Angeles traffic. “What if we wrote the book together?”

“Okay,” I told her, “but that means

we’re

writing it. Not me.”

What ensued were two years of weekends, school vacations, and evenings spent side by side at my computer, diligently crafting a story together. I think Sammy was surprised by how much hard work it is to sit and imagine for hours at a time; for my part, I learned that if you think it’s hard to get your daughter to clean her room, it’s even harder to get her to stay focused on finishing a chapter when it’s nice outside. We took turns typing, and literally spoke every sentence out loud. I would say one line, then Sammy would jump in with the next. The coolest moments were when we tripped over each other’s sentences and discovered we were thinking the same thing—it was sort of like we were having the same dream, so that in the act of writing, we were telepathic.

Sometimes when I’m reading a great book, I think, “Wow, I wish I’d been the one to think up that story line.” It has been an honor to have that same reaction when the story line was conceived by my own daughter. When Sammy first called me with her idea, I thought it was a great one. I hope, as you read

Between the Lines

, you think so too.

the beginning

the beginning

O

nce upon a time in a land far, far away there lived a brave king and a beautiful queen, who were so much in love that wherever they went, people stopped what they were doing just to watch them pass. Peasant wives who were fighting with their husbands suddenly forgot the reason for the argument; little boys who had been putting spiders in the braids of little girls tried to steal a kiss instead; artists wept because nothing they could create on canvas came close to approximating the purity of the love between King Maurice and Queen Maureen. On the day they learned that they were going to have a child, it is said that a rainbow brighter and grander than anything ever seen before arched across the kingdom, as if the sky itself was waving a banner of joy.

But not everyone was happy for the king and queen. In a cave at the far edge of the kingdom lived a man who had sworn off love. When you have been burned by fire once, you don’t leap into the flames again. Once upon a time, Rapscullio had expected to be living his own fairy tale, with his own happy ending, with a girl who had looked past his scarred face and gnarled limbs and had shown kindness to him when the rest of the world didn’t. In his mind, he replayed the day he had been shoved roughly into the mud by schoolmates—only to find the most slender white hand reaching out to help him up. How he had grabbed on to her, this angel, imagining her as his lifeline! He’d spent days composing poetry in her honor and painting portraits that never did her beauty justice, waiting for just the right moment to confess his love—only to find her in the arms of a man he could never be: someone tall, strong, and destined for greatness. Rapscullio had then grown darker and more twisted by his own hate every day. His portraits of his beloved had given way to intricate plans for revenge against the man who had single-handedly ruined his life: King Maurice.

One night, a roar rose from outside the gates of the kingdom, unlike any other sound heard before. The ground shook and a streak of fire shot through the sky, burning the thatched roofs of the village. King Maurice and Queen Maureen ran out of the castle to see a monstrous black beast with scaled wings the size of a ship’s sails, its eyes as red as embers. It stormed through the night sky, hissing sulfurous breath and spitting flames. Rapscullio had painted a dragon onto a magical canvas, and the demon had come to life.

The king looked at the panicked faces of his subjects and turned to his wife, but she had fallen to her knees in pain. “The baby,” she whispered. “It’s coming.”

Torn between love and duty, the king knew what he had to do. He kissed his beloved wife where she lay in bed with her maids attending her, and promised to be back in time to meet his son. Then, with a hundred knights armored in glinting silver, he raised his sword high and rode out across the castle drawbridge on a wave of bravery and passion.

But it is no easy feat to best a dragon. As he watched his loyal soldiers being torn from their mounts and flung to their deaths by the fiery beast, King Maurice knew that he had to take matters into his own hands. He grabbed the sword of a fallen knight in his left hand and, holding his own sword in his right, stepped forward to challenge the dragon.

As the night grew deeper, and the battle raged outside the castle walls, the queen struggled to bring her son into the world. As was the tradition for royal babies, the kingdom’s fairies arrived bearing gifts just as the newborn was delivered. They hovered, incandescent, above the queen, who was out of her mind with pain and worry for her husband.

The first fairy sent a spray of light over the bed, so bright that the queen had to turn away. “I give this child wisdom,” the fairy said.

The second fairy sprinkled a flash of heat that surrounded the queen where she lay. “I give this child loyalty,” she promised.

The third fairy had been planning to gift the royal child with

courage, because every royal child needs a healthy dose of bravery. But before she could offer her gift, Queen Maureen suddenly sat up in bed, her eyes wide with a vision of her husband on the battlefield, in the fierce clutches of the dragon. “Please,” she cried. “Save him!”

The fairies looked at each other, confused. The baby lay on the mattress, silent and still. They had attended plenty of births where the baby never drew its first breath. The third fairy tossed aside the courage she had been planning to give the child. “I give him life,” she said, the word swirling yellow from her lips into her palm. With a kiss, she blew it into the mouth of the newborn.

It was said in the kingdom that at the very moment Prince Oliver cried for the first time, his father, King Maurice, cried out for the last.

* * *

It’s not easy to grow up without a father. At age sixteen, Prince Oliver had never really been given the chance to just be a kid. Instead of playing tag, he had to learn seventeen languages. Instead of reading bedtime stories, he had to memorize the laws of the kingdom. He loved his mother, but it seemed to Oliver that no matter who he was, he would never be the person she wanted him to be. Sometimes he would hear her in her chambers, talking to someone, and when he entered there would be nobody with her. When she looked at his black hair and blue eyes, and remarked on how tall he was getting and how much he resembled his father, she always seemed to be on the verge of tears. As far as he could see, there was one critical difference between himself

and his heroic late father: courage. Oliver was smart and loyal, but he was a complete disappointment when it came to bravery. In an effort to make his mother happy, Oliver overcompensated, spending his teenage years trying to do everything else right. On Mondays, he held court so that the peasants could bring him their disputes. He conceived of a way to rotate crops in the kingdom so that the storerooms were always full, even in the harshest of winters. He worked with Orville, the kingdom wizard, to create heat-resistant armor just in case there was ever another dragon attack (although he nearly passed out with anxiety when he had to test the armor by walking through a bonfire). He was sixteen, fully old enough to take over the throne, yet neither his mother nor his subjects were in any hurry to make that happen. And how could he blame them? Kings protected their countries. And Oliver was in absolutely no rush to go into battle.

He knew why, of course. His own father had died wielding a sword; Oliver preferred to stay alive, and swords didn’t figure into that plan. It would have all been different if his dad had been there to teach him

how

to fight. But his mother wouldn’t even let him pick up a kitchen knife. Oliver’s only recollection of mock violence was at age ten with a friend named Figgins, the son of the royal baker, who would pretend to fight dragons and pirates with him in the courtyard, but one day Figgins vanished. (Oliver, in fact, had always wondered if his mother might have been behind this disappearance, in an effort to keep him from even

playing

at battle.) The only friend Oliver had ever had after

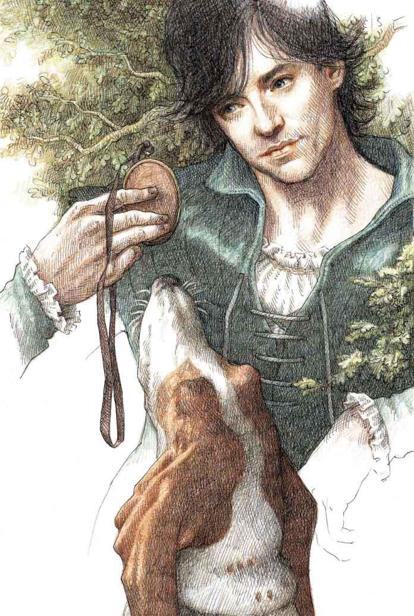

that, really, was a stray dog that appeared the very afternoon Figgins disappeared. And although Frump the hound was a fine pal, he couldn’t help Oliver practice his fencing skills. Thus Oliver grew up nursing a colossal secret: he was thrilled that he hadn’t ridden off into battle or jousted in a tournament, or even punched someone during an argument… because deep down, he was terrified.