Between Giants (54 page)

Authors: Prit Buttar

Tags: #Between Giants: The Battle for the Baltics in World War II

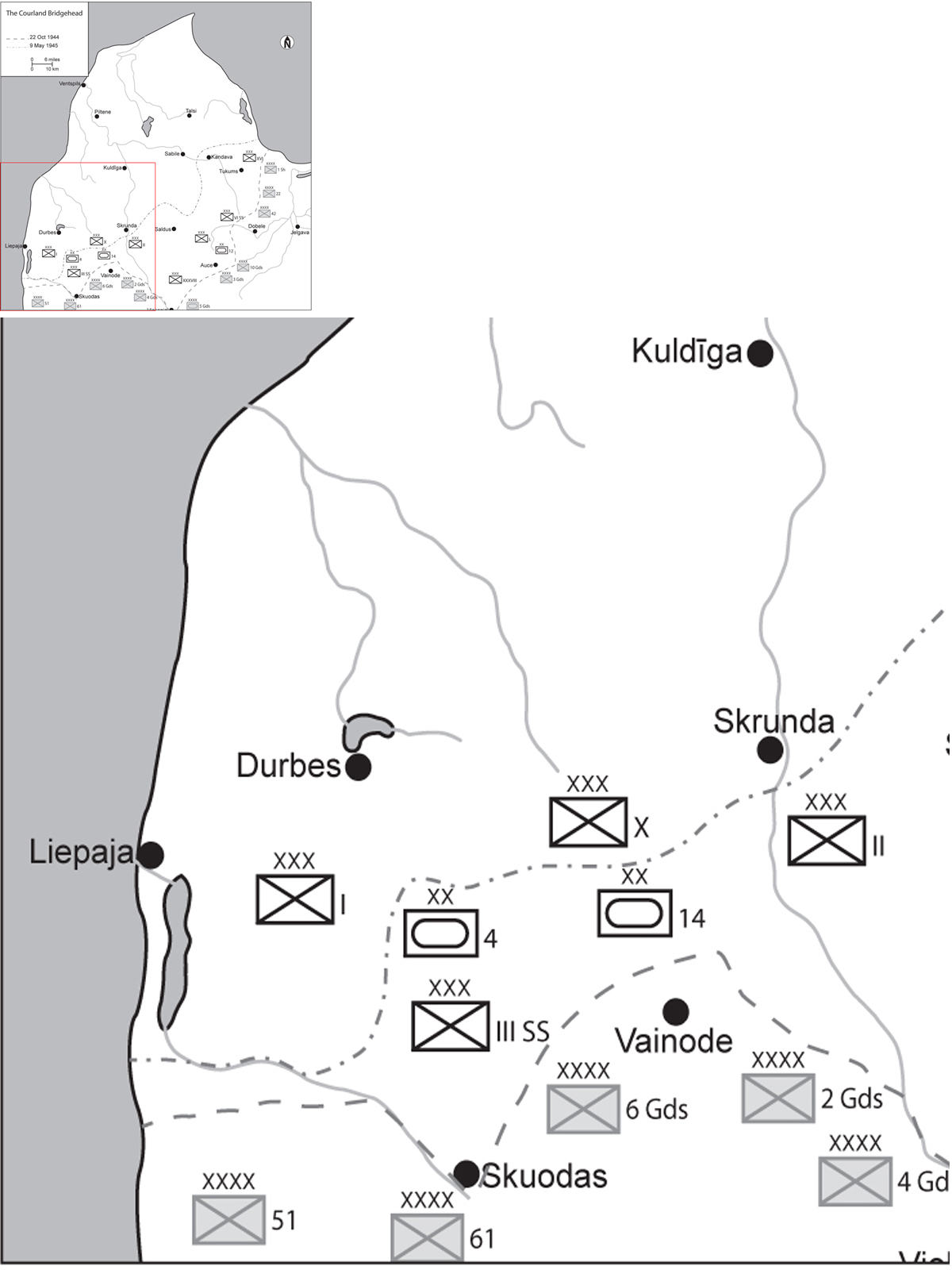

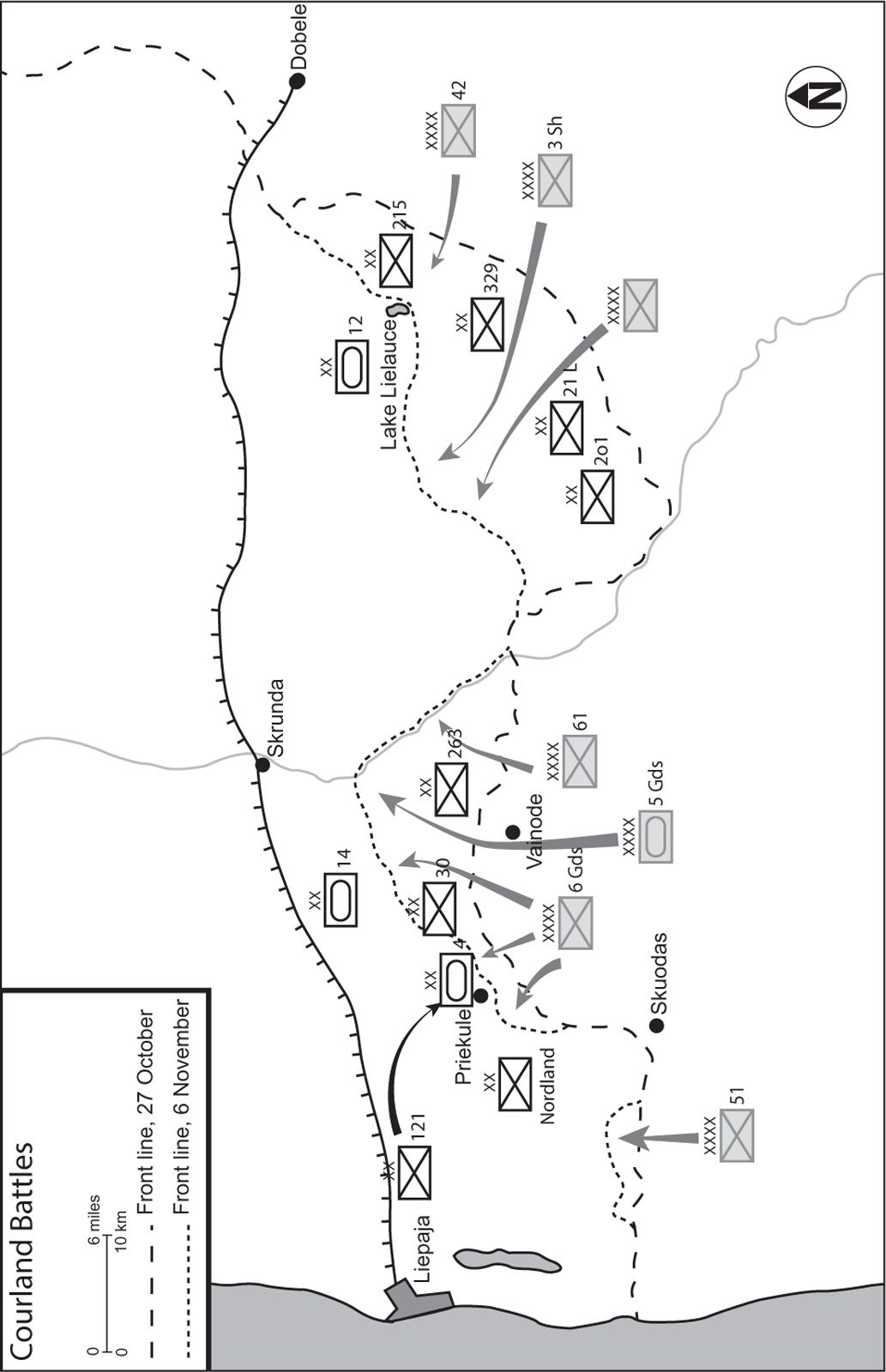

On 28 October, Bagramian’s forces attacked again, once more after a heavy artillery bombardment. The main effort fell on the German lines to the immediate east of Priekule, with heavy fighting raging all day in the woody and swampy terrain. 4th Panzer Division was involved in almost continuous combat until late afternoon; under pressure from four guards rifle divisions and at least two tank brigades, it was driven back in places, but barely a mile. The price paid by both the attackers and defenders was a heavy one. For his energetic leadership, Betzel was awarded the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross.

The following day, it was the turn of the Germans to mount an attack. 4th Panzer Division assembled a group consisting of its Panther battalion, a battalion of panzergrenadiers, and a battalion of combat engineers, supported by a regiment from 30th Infantry Division, and advanced on the village of Asīte from the north. Almost immediately, the assault group ran into the Soviet 29th Rifle Division, preparing to attack in the opposite direction. At close quarters, the two sides suffered further heavy casualties, and 4th Panzer Division was driven back to its start line. Here, it came under attack through the rest of the day, often having to improvise its defence: at one point, on the extreme eastern flank of the division, two Panthers, one towing the other, beat off an attack by seven Soviet assault guns and two tanks at close range.

8

While bitter fighting raged north of Asīte, the German lines immediately east of Priekule came under fresh attack when a battalion from the Soviet 51st Guards Rifle Division, with supporting tanks, penetrated into the extended lines held by a battalion of 4th Panzer Division’s panzergrenadiers. The situation was finally restored by a counter-attack late in the day. As darkness fell, Betzel’s division reported that it had lost nearly 180 men dead, wounded or missing, but had accounted for 20 Soviet tanks, including a Josef Stalin, seven assault guns and eight anti-tank guns. The division’s positions could only continue to be held, the division reported, if sufficient artillery support remained available, which would not be possible with the existing ammunition supply. The arrival of elements of 121st Infantry Division to relieve the battered panzergrenadiers to the east of Priekule was therefore particularly welcome.

The fighting continued the next day. The two infantry divisions on the flanks of 4th Panzer Division – 121st Infantry Division to the south-west, 30th Infantry Division to the north-east – came under heavy pressure, requiring repeated counterattacks to restore the front line. Although the front line barely moved, the defence was at a heavy price. By the end of 30 October, the four panzergrenadier battalions of 4th Panzer Division had fallen from an aggregate strength of nearly 1,500 at the beginning of the battle to only 700. Betzel warned his corps commander that the ongoing shortage of artillery ammunition, losses from the constant Soviet artillery bombardment and a shortage of winter clothing were all combining to degrade the combat-worthiness of his division.

9

Fortunately for the Germans, the Soviet forces facing them were also approaching exhaustion.

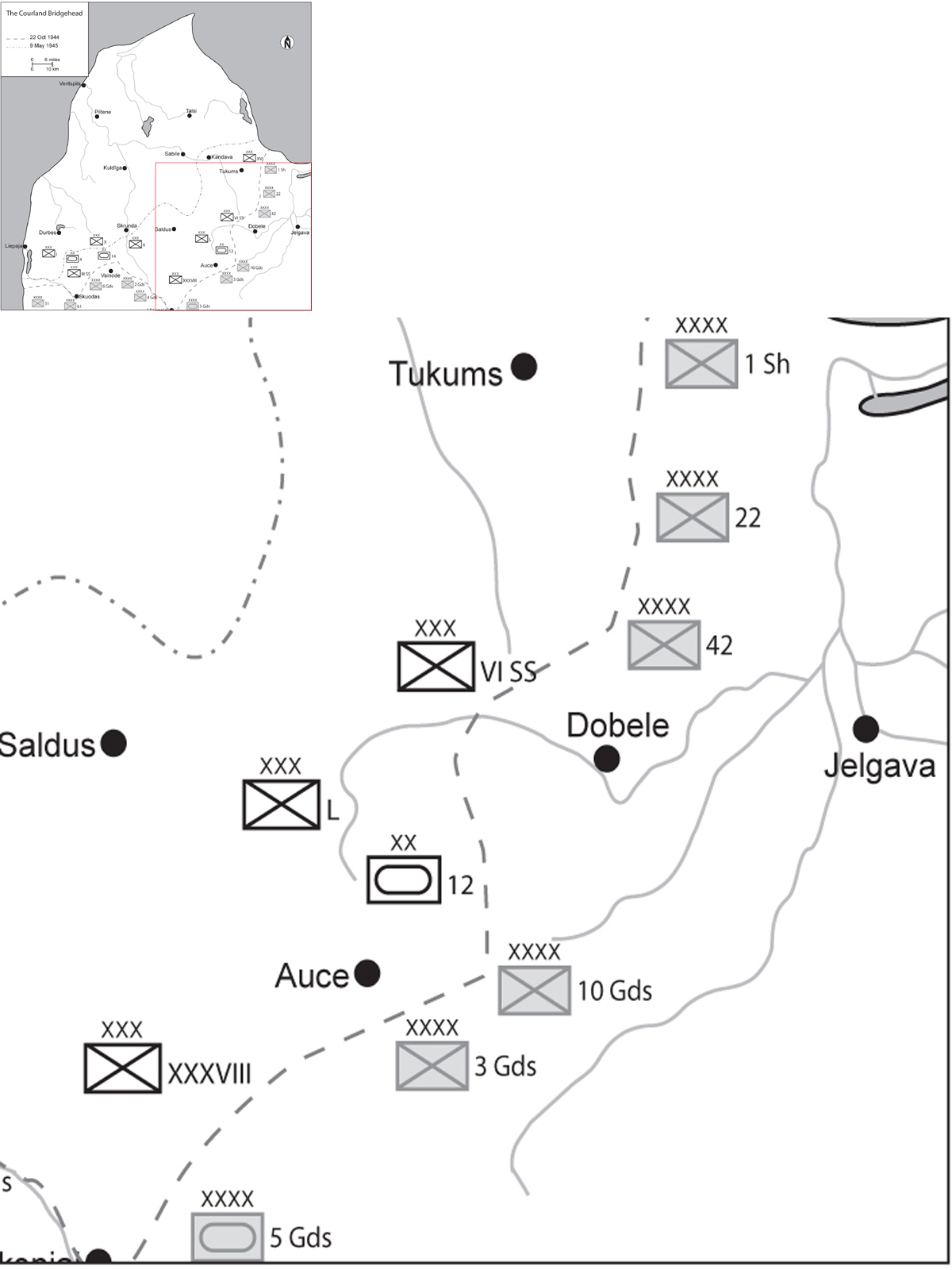

On 31 October, there were only limited attacks on the German lines held by 121st Infantry Division, with most of the effort coming further east, on the seam between 30th and 263rd Infantry Divisions. Here, the Red Army attacked with the 415th, 23rd, 356th and 212th Rifle Divisions, with 13th Guards Rifle Division in support as a second echelon. The two German infantry divisions were forced back about a mile, but again a decisive breakthrough eluded the Red Army. The constant presence of a battlegroup from 14th Panzer Division did much to hold the hard-pressed 30th Infantry Division together. As intelligence reports came of a fresh Soviet build-up, this time to the west of Priekule, 14th Panzer Division was extracted from the front line and ordered west. It was replaced by elements of 263rd Infantry Division, but Soviet observers spotted the withdrawal of the German armour and immediately attacked. 14th Panzer Division was immediately ordered back to its former sector, where it restored the front in further costly fighting. Fortunately for the Germans, the anticipated Soviet attack to the west of Priekule did not materialise.

Fighting continued for the next few days. The Soviet 3rd Guards Mechanised Corps remained uncommitted, to the constant concern of the Germans, who were aware of its presence. The Latvians of 19th SS Waffen-Grenadier Division were ordered to launch an attack on their western flank to improve the front line, but discovered at first hand the perils of using penal battalions. The attack was intended for 4 November, but two soldiers from a penal battalion, employed in construction of fortifications, deserted to the Red Army on 2 November, and presumably acting on information provided by them the Soviets launched a spoiling attack the following day. But the weather was deteriorating, and finally, on 6 November, Bagramian decided that he had had enough, even without committing his reserves, and his armies sat back to lick their wounds and await the next round of fighting:

In three days, our troops managed to penetrate only six kilometres into the enemy’s defences. The attack continued for a few more days, but every piece of ground in Courland could only be liberated after persistent and repeated attacks. Every farm, every height was contested bitterly. For the Fascists, this was a matter of life and death, while for the Soviet soldiers it was a military honour and duty to expel the Germans from the Homeland.

10

Yeremenko, too, made almost no headway. His troops managed to gain perhaps a mile or two of ground, though again at a terrible cost. The price of stopping the Soviet attack had also been high. 215th Infantry Division, which bore the brunt of the onslaught of Yeremenko’s troops, found that its fusilier battalion – effectively the division’s reserve formation – was reduced to barely company strength. The three regiments of the division were in a similarly battered state.

Although Bagramian concluded from captured documents and prisoner interrogations that the Germans did not intend to evacuate Courland, Moscow remained concerned that even a piecemeal evacuation of Courland would release troops for the defence of the German homeland. Consequently, although Soviet troops were withdrawn from the area – 61st Army, 2nd Guards Army, and 5th Guards Tank Army from Bagramian’s front, and 3rd Shock Army from Yeremenko’s front – both Bagramian and Yeremenko were ordered to maintain pressure on the German lines, to prevent even a partial evacuation.

The failure of the Red Army in the first battle of Courland was due to several factors. Firstly, the assault was prepared in haste, assuming that the Germans were still reeling from Bagramian’s surge to the Baltic. The strength of German defences therefore came as an unpleasant surprise. Secondly, the terrain that had played such a large role in holding up the German attacks in

Doppelkopf

and

Cäsar

proved to be equally difficult for the Soviet attackers. Thirdly, the deteriorating weather rapidly made any cross-country movement almost impossible, allowing the Germans to concentrate their anti-tank firepower on the few roads that were still usable.

Some of the fighting during the first battle of Courland resulted in Latvians fighting each other for their foreign masters. 19th SS Waffen-Grenadier Division took prisoner several individuals who informed their captors that they had only recently been conscripted into the Red Army from the eastern parts of Latvia. The general deterioration of the German position on the Eastern Front could not fail to have an impact on the Latvians still fighting with the Wehrmacht:

During this time, there was an apparent morale crisis … which manifested itself in increased desertion … [This] was caused by several reasons. After the vital defeats suffered by the Germans since summer 1944, and mainly [following] the loss of the Baltic area, many regarded the war as lost. Therefore, it was not worth sacrificing lives for. Others deserted hoping that as deserters they would get better treatment when captured by the Communists. Several left their units [after] rumours that … [19th SS Waffen-Grenadier Division] would be moved to Germany … Unwilling to leave their homeland, these man joined the organisation ‘Kureli’.

11

The Latvian General Jānis Kurelis had started preparing an organisation to fight against Soviet reoccupation of Latvia in the summer of 1944. Many of the Latvians who were most strongly opposed to a resumption of communist rule had exhorted their fellow Latvians not to flee the country – after all, they argued, a Latvia denuded of Latvians would be easy for the Soviet Union to colonise. Kurelis started to establish his first combat units around Riga in the late summer, and it seems that many of his officers believed that, as had been the case at the end of the First World War, the Western Powers would intervene to expel the Soviets from Latvia – therefore, keeping up some level of resistance against the Red Army was essential. Whilst this may seem a naïve point of view, it was a widespread one, with similar sentiments being expressed not only in the Baltic States but also by the Polish nationalist fighters of the AK. The eventual fate of the Kurelis Army is described later.