Between Giants (14 page)

Authors: Prit Buttar

Tags: #Between Giants: The Battle for the Baltics in World War II

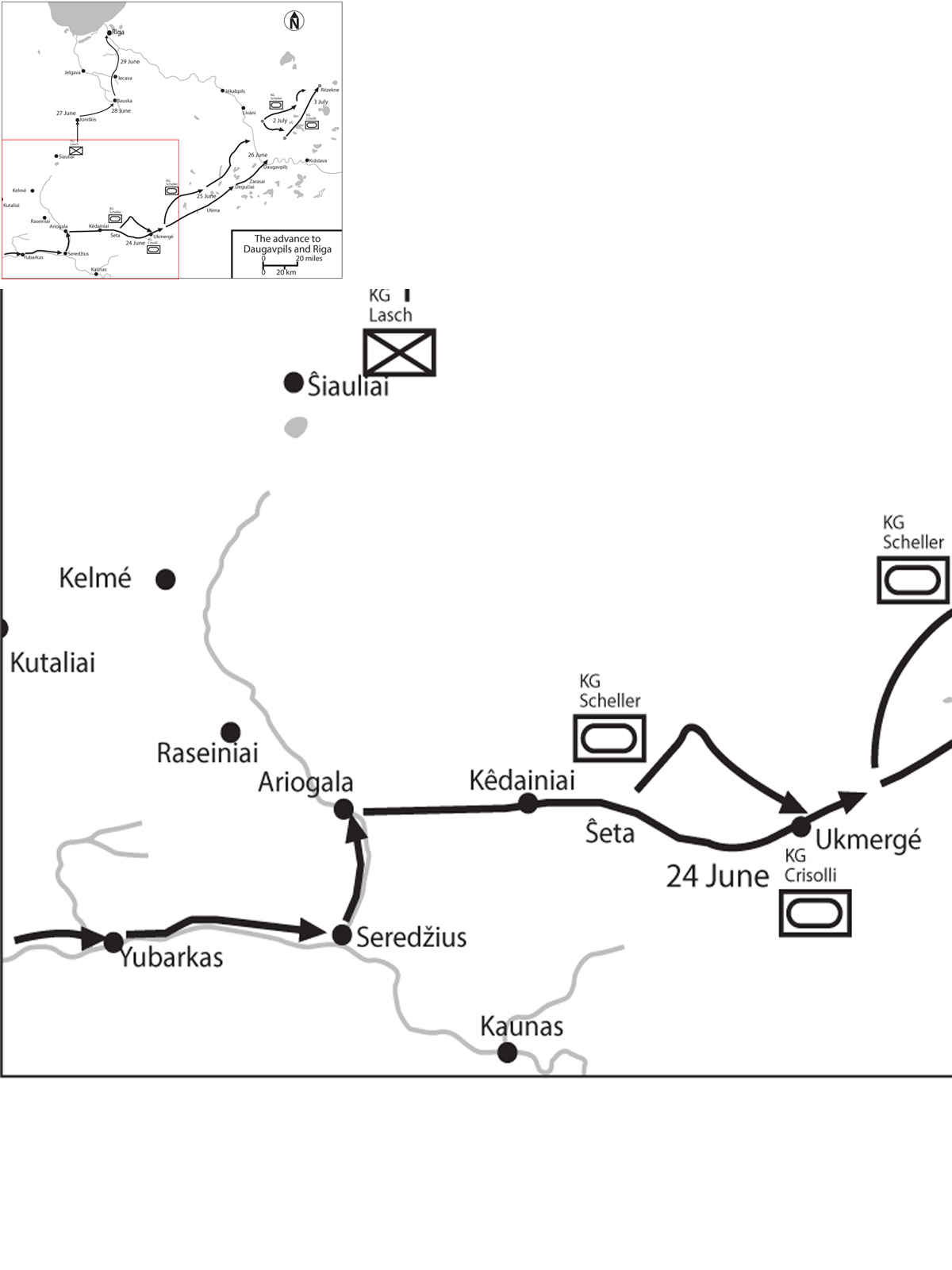

The initial objective was the River Dubysa, and Brandenberger divided his division into three battlegroups. On the right flank of the division was

Kampfgruppe Crisolli

, with the bulk of a motorised rifle regiment, a reinforced motorcycle battalion, a battalion of tanks, and a combat engineer company. On the left flank was

Kampfgruppe Scheller

, a more powerful group with a motorised rifle regiment, a battalion of tanks, a reinforced reconnaissance battalion, and combat engineers and additional forces.

5

Kampfgruppe Bodenhausen

was ready to support either battlegroup, or exploit their successes. It was anticipated that the main breakthrough would be made by

Kampfgruppe Scheller

, which would be preceded in its advance by an infantry regiment from the neighbouring 290th Infantry Division – the infantry would overcome the Soviet border defences, after which the armour and mechanised troops would push forward rapidly. True to the principles of

Auftragstaktik

, Brandenberger positioned himself with Scheller’s battlegroup.

Crisolli’s first wave included his combat engineers, led by Hauptmann Hallauer. They rapidly cleared the road of Soviet mines, despite being under constant fire, and the waiting armour was rapidly unleashed. Hallauer was badly wounded during his mine-clearing operation, and was awarded the Knight’s Cross; however, he died of his wounds two days later, before he could receive the decoration. The vehicles of Crisolli’s battlegroup suddenly found themselves advancing through open country – the Soviet defences on their sector proved to be no more than the immediate frontier line. Before 0600hrs, Crisolli signalled division headquarters that he had reached the outskirts of Yubarkas, and minutes later a tank platoon rattled across the bridges over the River Mituva. In a brief fight, Crisolli proceeded to secure the town. Meanwhile, further to the north-west, 8th Panzer Division’s reconnaissance elements which were moving forward in front of

Kampfgruppe Scheller

ran into tough resistance in dense woodland. Brandenberger immediately saw that the division’s breakthrough – and therefore its axis of advance – probably lay with Crisolli rather than Scheller, and at 0734hrs he advised his headquarters that he was moving to accompany the more successful battlegroup.

6

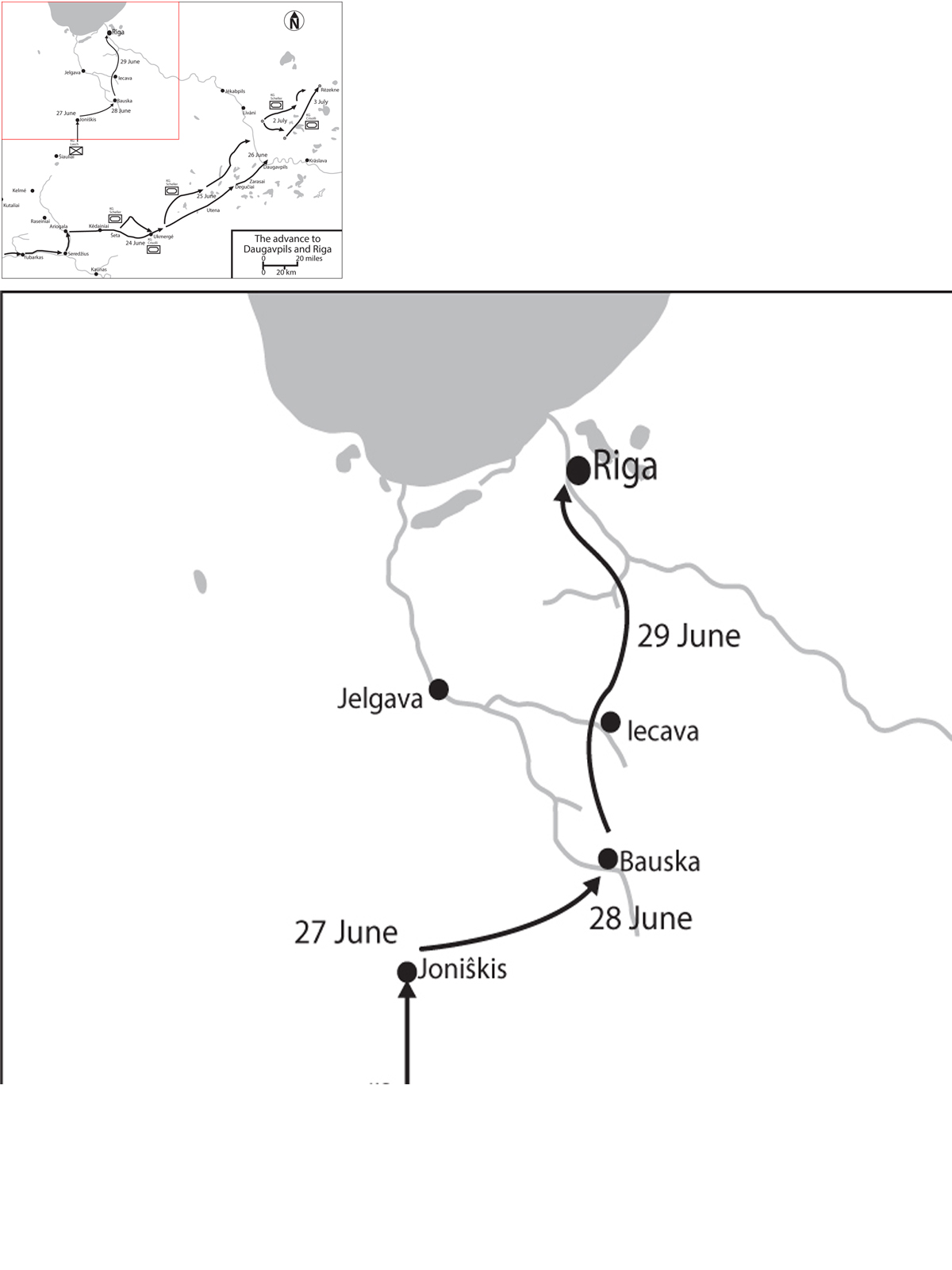

Crisolli pushed east under cloudless skies. Shortly after midday, the leading motorcycle company of his battlegroup reached Seredžius, a remarkable 40 miles east of Yubarkas. At about the same time, Generaloberst Hoepner, commander of 4th Panzer Group, visited division headquarters, where he was briefed on developments by Brandenberger’s chief of staff. As with Brandenberger’s own position with his lead elements, it was characteristic of German doctrine that Hoepner should visit his divisions in order to keep pace with developments. In a similar manner, Manstein visited 8th Panzer Division’s headquarters shortly after, and added his approval of Brandenberger’s plans, further urging that the division press on to reach Ariogala before the end of the day. He need not have worried. The division’s diary recorded:

The bulk of

Gruppe A

[Crisolli’s battlegroup] had meanwhile succeeded, without further fighting, in advancing to the Ariogala sector, where the flanking high ground was occupied by the enemy. The bridge from Ariogala was unusable by vehicles, but a ford with a firm bed, suitable for all vehicles, was discovered in close proximity to the road, across which the tanks rapidly began to cross, followed by the armoured personnel carriers, for deployment against the high ground at Ariogala.

This rapid thrust, which was certainly not expected by the enemy, succeeded in breaking enemy resistance, including armoured cars, and in capturing the high ground covering the ford.

At the same time, the assault on the main road bridge of Ariogala, which had been ordered by the division commander, supported by our artillery and the tank battalion, was carried out and completed successfully by 1725.

7

A few minutes later, Manstein joined Brandenberger at the vital road bridge over the Dubysa that had just been captured. Crisolli’s battlegroup had advanced over 48 miles from its start line, but there was still daylight. Within the limits of remaining fuel, Brandenberger was ordered to press on with his tanks towards Kadainiai. Barely two miles from Ariogala, the German spearhead ran into troops that it mistakenly identified as elements of the Soviet 5th Tank Division, and was forced to halt at 2300hrs. In less than 20 hours, these leading German troops had covered 55 miles from their starting positions. 8th Panzer Division was admittedly dispersed over a large area, with

Kampfgruppe Scheller

still struggling through the border fortifications, but the day’s objectives had been achieved with time to spare.

8

Gustav Klinter, moving forward with the division’s motorised infantry, remembered his first sight of Soviet dead:

The air had that putrefying and pervasive burnt smell reminiscent of the battle zone and all nerves and senses began to detect the breath of war. Suddenly, all heads switched to the right. The first dead of the Russian campaign lay before our eyes like a spectre – a Mongolian skull smashed in combat, a torn uniform and bare abdomen split by shell splinters. The column drew up and then accelerated ahead – the picture fell behind us. I sank back thoughtfully into my seat.

9

The onset of hostilities had converted the Baltic region into the North-west Front; all along it, Kuznetsov’s armies struggled to bring their infantry forward from their barracks. The regiments deployed along the border were scattered and annihilated during the morning, and many of the columns hurrying forward, harassed from the air, ran into the advancing German forces, which sent them reeling back in disarray. The Soviet 48th Rifle Division was spotted by German bombers and subjected to a sustained bombardment; it suffered heavy losses before it could even get into battle. Soviet commanders at all levels struggled to keep up with events. The few reports reaching them from the front line spoke of unimaginable disasters, and there was little or no information available from aerial reconnaissance. At the very highest levels, Stalin’s subordinates argued about who should wake their leader and tell him what was happening. Some, like Georgi Maximilianovich Malenkov, Chairman of the Council of Ministers, even attempted to bully those telephoning Moscow to change their reports.

10

The Politburo met an hour after the German invasion started, and Stalin continued to refuse to authorise full-scale counter-attacks – it was possible, he argued, that the fighting was due to provocative action by German generals, acting without the knowledge or authority of Hitler. It was only after Schulenburg was summoned to the Kremlin, where he told Molotov that Berlin had been forced to take action because of Soviet troop concentrations near the border, that Stalin finally accepted that his nation was indeed at war.

Acting effectively in an intelligence vacuum, the Soviet People’s Commissariat of Defence – essentially the defence ministry – sent Directive 3 to Kuznetsov:

While firmly holding on to the coast of the Baltic Sea, deliver a powerful blow from the Kaunas region into the flank and rear of the enemy Suvalki grouping, destroy it in cooperation with the Western Front, and capture the Suvalki region by the end of 24 June.

11

This order required Kuznetsov and his neighbouring Western Front to the south-east to cooperate in order to destroy what amounted to Hoepner’s 4th Panzer Group, Busch’s 16th Army, and parts of General Hermann Hoth’s 3rd Panzer Group in the German Army Group Centre. Even without the losses already incurred, such an undertaking would have been beyond the power of the two Soviet fronts. In the circumstances, under hostile skies and with major casualties already reducing their strength, it was a ludicrous order. In any event, General Dmitri Gregorovich Pavlov’s Western Front was in even worse shape than Kuznetsov’s front, driven back in chaos by two German panzer groups. Kuznetsov received the order at 1000hrs on 23 June, by which stage he had already issued orders to his two mechanised corps to begin their counter-attacks. His pre-war plans called for these counter-attacks to be made against the main enemy concentration, but in the absence of clear information about German movements, he simply ordered the two corps forward according to pre-planned axes of advance into the area where the Germans appeared to have made the most progress: 12th Mechanised Corps would advance from Šiauliai and move south-east, while 3rd Mechanised Corps would attack from Kėdainiai towards the north-west.

12th Mechanised Corps was commanded by Major General Nikolai Mikhailovich Shestopalov, a former cavalryman. He dispatched his 23rd and 28th Tank Divisions towards the enemy, but the attack was doomed from the start. Ammunition and fuel shortages, combined with insufficient time to gather the various sub-units into an orderly whole, and a complete lack of knowledge of the whereabouts of German units, resulted in a piecemeal attack.

23rd Tank Division was deployed to the west of 28th Tank Division. Near Kutaliai, 23rd Tank Division encountered elements of the German 11th and 1st Infantry Divisions, and though it made some initial progress, a confused battle continued for a day before the exhausted Soviet division was forced back, abandoning many of its tanks as they ran out of fuel. A little to the east, the Soviet 28th Tank Division attacked south against the 1st and 21st Infantry Divisions; the two sides first encountered each other at dusk on 23 June:

Between 12 and 15 tanks drove down the road running south-east from Kaltinėnai. At the same moment, Gefreiter Hasse from 14 Coy, Inf.Reg.22, had brought his gun into position at the road fork a kilometre north of the Butkaičiai estate. The gunner shot up six of the rapidly advancing tanks at close range, even though the gun was almost overrun.

12

Hasse was probably fortunate that the tanks he faced were either T26 or BT7 models; his 37mm gun would have been ineffective against the heavier Soviet armour.

The German axis of advance was towards the north-east, while the Soviet armour was attempting to attack southwards. Three days of fighting followed, with the increasingly bewildered Soviet units struggling to react to enemy movements. Through a mixture of enemy action, mechanical breakdowns and fuel shortages, the two Soviet divisions lost all but 45 of their original 749 tanks, and were driven back in a chaotic retreat.

13

For the commander of 28th Tank Division, Ivan Danilovich Cherniakhovsky, it was a chastening baptism of fire. He survived the setback, and eventually rose to command a front during 1944–45.