Bertie Ahern: The Man Who Blew the Boom: Power & Money (46 page)

Read Bertie Ahern: The Man Who Blew the Boom: Power & Money Online

Authors: Colm Keena

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Europe, #Leaders & Notable People, #Political, #Presidents & Heads of State, #History, #Military, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Elections & Political Process, #Leadership, #Ireland, #-

AHERN, EUROPE AND MONETARY UNION

I

n the wake of the Irish banking collapse—perhaps the greatest ever in relation to losses as a proportion of a country’s economy—the Government commissioned an inquiry into how it could have happened. Prof. Patrick Honohan had been appointed Governor of the Central Bank, the first holder of the office in a long time who was not a former secretary-general of the Department of Finance. (Ireland’s practice of appointing former secretaries-general was an exception in Europe, where it was seen as contrary to the fostering of independence.)

Seen from the Fianna Fáil backbenches, Honohan was an outsider. While the party, and Ahern in particular, had shown an aversion to informed public debate and analysis during the period 1997–2008, Honohan was the sort of man who was most happy in an economics workshop exploring the solidity of the arguments being put forward. His appointment, brought about by the depth of the crisis in which Ireland found itself, was part of a process whereby the dislike of data and argument that had marked the previous decade was swapped for the opposite.

As part of the inquiry, two outside experts, Klaus Regling and Max Watson, were appointed to draft a report on the international and domestic backdrop to the disastrous performance of the Irish banking sector. The report in turn led to a consideration of its contents by an all-party committee of the Oireachtas, the Committee on Finance and the Public Services, which received assistance from a professor of economics at Trinity College, Philip Lane. The committee reported in November 2010 and recommended such measures as multi-year budgets and the establishment of independent councils that would comment on the economy and the performance of budgetary policy so as to generate a more informed budgetary debate. (The distance between this idea and the practices of McCreevy is worth dwelling on.) The report recognised that during boom periods the public finances should be run in a counter-cyclical way. In other words, the public finances should be used to cool booms and counter economic slowdowns. A rainy-day fund would be created, into which money would be put during boom years, thereby dampening economic growth during the upswing in the economic cycle. The money could be used to stimulate the economy during slumps and would stop the state having to go to the markets to borrow. It also envisaged a lot more economic data being collected and analysed, and the boosting of the intellectual performance of the Department of Finance.

Almost everything in the report was an implicit criticism of the way the state was run during the Ahern Governments. ‘The setting of formal fiscal frameworks forces government policy to avoid short-termism or “capture by elites”.’ In the press release accompanying the report it was stated that in a single European currency the state did not have all the tools it formerly had to control macroeconomic policy (devaluation of the currency and the setting of exchange rates), so the Government had to pay attention to the new environment in which it operated when considering its economic policies. Fiscal policy would have to be run in a ‘new way’, said the committee chairperson, Michael Ahern, in his introductory comments.

Considering the fact that the single currency was launched on 1 January 2002, and had a long lead-in, it was a surprising statement. It was the equivalent of saying, half way up a high mountain, that in future when setting out on a hike the family would put on appropriate clothes and bring something to drink. Debate had taken place in the period before the euro on how economic policy would have to accommodate the new circumstances, but it had not been absorbed by Ahern or his Governments. When I asked Micheál Martin to what extent the loss of the interest rate mechanism featured in the Government’s consideration of fiscal policy, he was clear that the new currency was welcomed for providing low interest rates. That it required the introduction by the Government of fresh ways of dampening down economic activity when the economy was threatening to overheat appears not to have framed Government debate on fiscal policy.

According to Laffan, an element of ‘soft Eurosceptism’ emerged in the first Ahern Government as the 1990s drew to a close. Laffan, who is regularly turned to as an expert on

EU

affairs, recalled a comment made to her at a party.

It was a very casual comment. Someone said to me, ‘Ah, Brigid, Europe is over. You are going to have to find something else to do.’ It was someone senior in Fianna Fáil, not a politician. And I felt immediately that something was happening, that that person wouldn’t have said that to me if they weren’t operating in a milieu where that was being said. It was 1999. We’d had a great roar of the Tiger, very high growth rates, so obviously there was a sense of arrogance.

At the time, she was with the Policy Institute in Trinity College and was working on a paper entitled ‘Organising for a Changing Europe? Irish Central Government and the European Union’. She went around the system interviewing senior politicians and civil servants. ‘I picked up on the fact that somehow or other Europe had gone down the hierarchy in terms of interest.’ The state had just come through some budgetary talks with the

EU

and secured that issue for the coming period. At the end of her paper she wrote that Ireland was in danger of losing its moorings on Europe. ‘And it did.’

Reviewing the change in Ireland’s relationship with Europe, Laffan cited the row McCreevy had had with the European Commission and the European Council in early 2000 over budgets that the Europeans believed were unwise because they were pro-cyclical or were boosting rather than calming matters. Ireland’s economy was booming, but interest rates, because of the currency project, remained low. (Normally interest rates are raised to cool a booming economy and lowered to boost a flagging one. Euro-zone interest rates are set to suit the needs of the entire currency area.) McCreevy ‘put on the green shirt’, according to Laffan. This began a period when, for the first time, the Commission was portrayed in Ireland as other than its ‘best friend’.

In a speech to the American Bar Association in the Law Library in Dublin in July 2000, Mary Harney said the relationship of the Irish people with the United States and the European Union was complex. ‘Geographically we are closer to Berlin than Boston. Spiritually we are probably a lot closer to Boston than Berlin.’ Ireland, she said, was a country that believed in economic liberalisation, the incentive power of low taxation. Ireland had sought to steer a course between the European and American outlooks but had ‘sailed closer to the American shore than the European one.’ She didn’t want key economic decisions being taken at the Brussels level. Ireland wanted regulation but not over-regulation. She repeated the views in a later article in the

Irish Times

, and the Boston v. Berlin idea entered popular debate on Ireland’s

EU

membership.

In September 2000, in an address at Boston College, Massachusetts, the Minister for the Arts, Heritage, the Gaeltacht and the Islands, Síle de Valera, said she was frequently asked when abroad about the Celtic Tiger. A number of factors had helped create it, including ‘our ability to take advantage of our membership of the European Union.’ However, the development of the union in the period since Ireland joined had seen decisions other than economic ones being taken. ‘We have found that directives and regulations agreed in Brussels can often seriously impinge on our identity, culture and traditions. The bureaucracy of Brussels does not always respect the complexities and sensitivities of member-states.’ De Valera said she looked forward to a time when Ireland would ‘exercise a more vigilant, a more questioning attitude to the European Union.’ It was, according to Laffan, the most Euro-critical speech ever delivered by a serving Irish minister. She does not believe that such speeches would have been made when Ireland was receiving large budget transfers from Europe.

This developing tone of ‘soft Euro-scepticism’ fed into the Nice Referendum in June 2001, in which a low turn-out voted 54 to 46 per cent against, creating a dilemma not only for Ireland but also for the union on which it was so heavily dependent. According to Brigid Laffan,

Suddenly we had a problem with the

EU

, and Ahern understood very quickly that he needed to get Ireland back onside. One thing about Ahern is that he recognised constraints pretty quickly. He responded very quickly . . . And that then dampened down that Euro-sceptic end of the cabinet.

While the tension between Dublin and Brussels created by McCreevy’s expansionary budgets in the period before the 2002 election eased with the downturn of those years, Laffan believes that Europe continued to be concerned about Ireland’s economic policies, the erosion of its tax base and its pro-cyclical budgetary policy.

However, Ireland was the poster boy of the Baltic and Eastern European countries that were lining up to join the

EU

. For them Europe had been a huge stabilising factor in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, since it was clear that nationalist tendencies would have to be suppressed and parliamentary democracy developed if they were to gain entry to what they saw as the rich men’s club. Acccording to Laffan, politicians and senior civil servants from these countries rolled in to Dublin wanting to talk about Ireland’s experience of

EU

membership.

Ireland had been a poor country and was now a rich country. And in the history of the

EU

, Ireland is the only country that came in a poor country, below 75 per cent of the average per capita income, and converged [with the average income]. No other country has ever converged except Ireland. It is an extraordinary achievement. Right up to before the Single European Act [1987], our per capita incomes were still way down, around 65 per cent of the

EU

average. We were still way off, until the single market came. I’m convinced structural funds helped, but it was the single market that drove it in the end, coupled with the devaluation in the early 1990s.

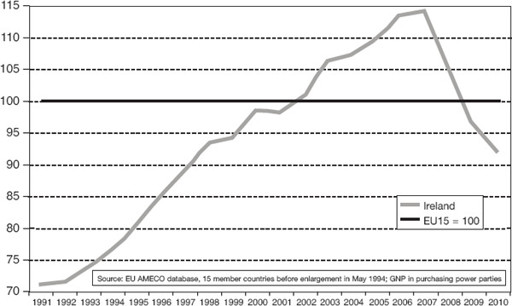

Fig. 5: Income per capita relative to

EU

average, 1991–2010

Source: Rob Wright, report on Department of Finance. Reproduced with permission.

There was another difficulty. The single currency had a set of rules governing borrowing and debt levels for member-states. Seen from the point of view of these rules, Ireland was again the star pupil. It was running government surpluses and paying off its national debt, driving it down to levels below the European average. How then could it be criticised as an errant member of the euro club?

The period when Ahern was in power was one of tectonic shifts in the global economy. Countries like China and India were selling ever-increasing amounts of manufactured products to the richer countries. The huge savings they amassed became available for the global financial system, and this in turn tempted many countries, companies and people to take on excessive debt. Western countries found themselves involved in a heavily globalised marketplace with competitor economies that had wage levels far below the Western norm. Technology boosted the capacity for outsourcing. Blue-collar income in many Western economies, including the United States, has fallen in real terms over recent decades, and the income level of the middle classes is treading water. Capital, meanwhile, has benefited from lower wage costs and access to the global marketplace.

The development of the European banking system saw banks moving into new markets. New entrants into the Irish market increased competition at the same time as money became more easily available in the international markets. This increased banking competition and new access to unlimited cheap money occurred as the Irish economy had just come through a period of exceptional economic growth. As Regling and Watson put it,

this fostered expectations of a continued rise in living standards and in asset values. Another factor, with even deeper roots, was the strong and pervasive preference in Irish society for property as an asset, and the fact that Ireland never experienced a property crash.

Regling and Watson made it clear in their report that they were not saying that what occurred was inevitable. They pointed out that prudent Government policies aimed at mitigating the risks of the boom-bust cycle could have increased the chances of a soft landing. However, the opposite path was the one chosen.

Fiscal policies heightened the vulnerability of the economy. Budgetary policy veered more towards spending money while revenues came in. In addition, the pattern of tax cuts left revenues increasingly fragile since they were dependent on taxes driven by the property sector and high consumer spending.

Ireland was also unusual in having so many property-related tax reliefs but no property tax. Regling and Watson pointed out that such was the level of tax reliefs available during the Ahern years that in 2005 the

OECD

calculated that the cost of giving these reliefs was greater than the actual amount of income tax collected.