Beneath the Sands of Egypt (10 page)

Read Beneath the Sands of Egypt Online

Authors: PhD Donald P. Ryan

If Ankhwennefer could awake from his extended slumber, he'd have one heck of a surprise. He has gone from once serving the temple of Min and being afforded a proper burial to having his coffin unearthed and his body sold as a tourist commodity, only to be relocated to a history museum's storeroom in a cool, forested part of the world he never knew existed. What a long, strange trip it was for him, and what an interesting learning experience for me.

Â

A

NOTHER DEVELOPING INTEREST

of mine was the documentation of ancient sites. In the case of Egypt, the detailed survey and

description of ancient monuments remains an important priority, as many are suffering rapid decay due to a variety of factors, both human and natural. Tourism, agricultural and residential expansion, and natural erosion all take their toll, and the need to document, if not preserve, these precious remnants of the past is vital. Ideally, there will at least be as detailed a record as possible of what once existed, whether the actual monuments withstand the abuses of time or not.

Enter the epigraphers. Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions and the art of recording them. There are several methods. At its simplest, a skillful artist sketches an inscription or copies a painted wall with pencil, ink, or watercolors. Howard Carter began his Egyptological career doing just that, first coming to Egypt at age seventeen to document ancient inscriptions and paintings, and his work was some of the best of this sort ever produced. Other epigraphic techniques include physically tracing inscriptions or paintings onto thin paper or clear plastic sheets. While typically involving direct contact with a decorated wall, these are much less intrusive than some of the older methods, which involved making molds with plaster or wet paper.

Within a few years of the invention of photography, Egypt became a popular focus for the new technology. Its ancient and contemporary cultures provide plenty of alluring images, but photography could also be applied to epigraphy. Both recording by hand and photography, though, have their drawbacks. While sketching and painting can be compromised by the subjectivity of the artist, the so-called objective details of a photograph can be subdued by such factors as shadows and the inclusion of irrelevant features. The most effective approach is to use both.

The University of Chicago is at the cutting edge of documentation, and its Epigraphic Survey has been busy in Egypt for many

decades. With money contributed by John D. Rockefeller, the facility in Luxor known as Chicago House was established in 1924 and remains active during the six cooler months of the year. Its stated goal is “to produce photographs and precise line drawings of the inscriptions and relief scenes on major temples and tombs at Luxor for publication.”

During my first trip to Egypt, I met a scholar who once worked at Chicago House and was willing to explain their method of documentation. A large-format black-and-white photograph is taken of, say, an inscribed temple wall. The image is developed into a print, and an artist then traces with ink over the salient hieroglyphs or other decoration displayed in the photograph. It is taken back to the wall and any missing or unclear details are filled in and refined. Eventually the photographic image is bleached out, leaving only a line image that is then corrected, then corrected again if necessary, until a consensus of accuracy is reached by the Egyptologists. This sometimes involves standing on very tall ladders perched against gigantic stone columns and plenty of time in the heat. Precise artistic rules are used, and the end result is an incredibly accurate facsimile that becomes part of a published volume that will serve as a permanent record, even if, sadly, the original monument should crumble to dust. It is a long, exacting, and expensive procedure. People sometimes joke that the process of documentation has taken much longer than it took the Egyptians themselves to actually build and decorate some of these temples. The careful work nonetheless is certainly worth the effort.

Although I wasn't particularly in a position to work within the lofty world of Chicago House, my interest in epigraphy brought me to a place relatively closer and actually much more familiar to me: Hawaii. My parents first took me there when I was nine years old, and I loved everything about it. We were frequent visitors, and

while it wasn't exactly Egypt, I found its culture, environment, and archaeology likewise captivating, and I was actually able to apply some of my interests in epigraphy to ancient sites found on these beautiful tropical islands.

When Captain Cook encountered the Hawaiian Islands in 1778, the native population had no writing system. They were certainly sophisticated in numerous ways and maintained a wealth of oral traditions that had been memorized and recited for generations, but there was no Hawaiian script until after the first American missionaries arrived in 1820. However, there are many ways to communicate, including artistic expression, and what really interested me were petroglyphs: symbols and other drawings scratched, incised, or pecked into stone surfaces and often found in very remote or abandoned places. In the Hawaiian language, they are known as

kiâi pohaku

â“images in stone”âand in many ways they are a mystery that is difficult to decipher.

Being exposed to the elements in a hot, rainy climate, the petroglyphs, like the monuments of Egypt, are subject to natural deterioration. Worse yet, nonnative species such as kiawe, a tree related to mesquite, have taken root in many coastal areas and thrive like weeds, their strong-growing trunks and roots shattering the lava with the potential of decimating irreplaceable ancient records. In addition, the wild descendants of animals such as goats and donkeys that are not native to the islands roam the lava beds consuming the tasty leaves and sweet seed pods of the kiawe only to disperse and deposit seeds in tiny cracks with their dung and further the destruction.

Modern development, too, has had its effect, and once-desolate areas have become resorts and expensive communities, putting people, some with vandalistic tendencies, in close proximity to these precious images from the past. Indeed, Polynesian petroglyphs are

very worthy of epigraphic attention, and in between my journeys to Egypt in the early 1980s, and several times thereafter, I went to Hawaii to record and preserve what I could.

On the western coast of the “Big Island” of Hawaii, one can find a region called Kona. It's on the dry side of the island, and a significant portion of its landscape is miles upon miles of black lava descending to the sea from a large, hulking volcano named Hualalai. Kona had been a home base for the great warrior-chief Kamehameha, who unified the islands into a kingdom, and it was here that the first missionaries came with their goal of Christianizing Hawaiian society. Today the town of Kailua-Kona is a delightful population hub and tourist destination.

About a dozen miles north of the town is an ancient region called Kaâupulehu. The name itself means “roasted breadfruit” and derives from an ancient legend in which the volcano goddess, Pele, visits two sisters in the area. (Legend has it that one sister shared her breadfruit with the incognito goddess, and her home was spared during a volcanic eruption.) Up until about the 1960s, the coast here was accessible only by boat or by hiking for miles on old trails. Around that time a man named Johnno Jackson came up along the coast and laid the foundation for what would become the Kona Village Resort, a quiet complex of Polynesian-style huts that continues to attract those seeking a simple yet luxurious hideaway. And it just so happened that in the lava field right behind the resort lay one of the most impressive collections of petroglyphs to be found in the Hawaiian Islands, if not in all of Polynesia.

Old Kaâupulehu had once supported a village on a beautiful bay, but by the mid-twentieth century there were just a few inhabitants at best. Most everyone had moved to towns with modern conveniences. When an archaeological survey came through in the early 1960s, the researchers found mere remnants of civiliza

tion: some stone platforms that served as the floors of grass houses, shelter caves littered with seashells from ancient meals, some well-hidden burial caves, and the petroglyphs. Unlike others found in the Islands, the petroglyphs at Kaâupulehu are distinctly different. At other sites one tends to find simple carvings of sticklike figures and a lot of circles and dots. At Kaâupulehu the style and motifs are remarkably unique, some appearing dynamic and almost animated rather than static. There are many dozens of depictions of what appear to be canoe sails, some showing ripples in their fabric as if being blown by the wind. There's a figure of a man fishing with a long line outfitted with huge hooks, a group that appears to depict two men carrying a body on a pole, and there are several examples of men wearing headdresses as if chiefs. There are also numerous examples of what in Hawaiian are called

papamu,

rectangular patterns of dots pecked into the rock, which some locals will interpret as venues for the playing of

konane,

a checkerslike game involving black and white stones.

It has been proposed that the profusion of sail motifs suggests that Kaâupulehu might have once served as the site of a kind of sailing school for canoe voyaging, and perhaps the

papamu

are actually a teaching tool in which white stones could be placed in various holes to duplicate the patterns in the sky used in celestial navigation. As opposed to the typical static norm, the petroglyphs at Kaâupulehu were excitingly dynamic.

Sadly, several of the most intriguing examples had suffered rudely from attempts to bring their mystery elsewhere. Some had been excessively rubbed, their edges degraded from repeated copying by paper and crayons. Worse yet is an example in which latex was poured directly into a petroglyph in an attempt to make a cast. The damaging result was scarring with latex embedded in the porous surface of the lava. Likewise, an ill-considered attempt

to use resin for the same purpose left a disastrous result.

Motivated by a desire to preserve these precious items, accompanied by what I had learned about the scholars at Chicago House and their epigraphic methods, I asked the manager of Kona Village if I might attempt to document the petroglyphs on that property. Being fascinated with Hawaiian history and culture himself, he enthusiastically agreed. I set out for Hawaii alone, old survey reports and maps in hand, and headed for the Kona lava fields.

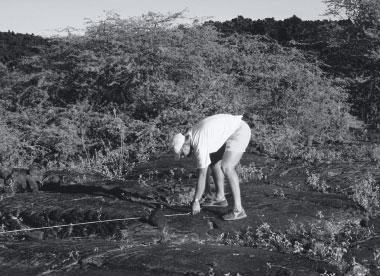

An example of Hawaiian petroglyphs studied by the author. Are they fighting or dancing?

Denis Whitfill/Experimental Epigraphy Expedition

The first step was to locate as many of the petroglyphs behind the village as I could. It was an incredibly daunting task as the area was thickly infested with the nasty kiawe trees, whose thorns tore at my skin and clothing and whose leafy debris covered much of the lava surface. Scattered jagged chunks of black rock surrounding the

trunks of the kiawe were a constant reminder of the destruction taking place in the midst of this amazing site. How many petroglyphs were being literally exploded apart by these botanical outsiders? And it was genuinely hot. Not the dry heat of the Egyptian desert but the humid heat of a tropical island, accelerated by the black surface of the lava rock, which in places became too hot to touch.

As I crawled across the lava with brooms of various sizes, the task of locating all the petroglyphs, let alone effectively documenting them, was quickly turning from my imagined jolly concept of easy, fun Hawaiian epigraphy to something bordering on the truly arduous and impractical. The amount of plant debris to sweep away so that I could confidently declare that all petroglyphs had been revealed was immense. Also, the solo surveying technique I had contrived was nearly impossible to implement, as the kiawe interfered with my line of sight. Lighting, too, was an issue, and some petroglyphs visible in the early-morning or late-afternoon light were barely discernible for much of the day. It was terribly frustrating.

However, I had more success in another area. About half a mile away, across the lava desert, are scattered groups of petroglyphs in an area that the kiawe have yet to conquer, some of which are truly exceptional and vibrant. In one such example there is a dramatic figure that seems to be wearing a tall, elaborate headdressâand two men dancing or fighting with paddles over their heads. Even farther along the harsh landscape is another site where stone shelter walls still stand in isolation within just a few yards of a lava flow that cut across the landscape in 1801. The lava devastated everything in its path and filled in a good part of the nearby bay, and one wonders what might have lain beneath. Nearby are more

papamu,

sails, and a curious, deeply carved petroglyph depicting a six-toed foot.