BELGRADE (19 page)

Authors: David Norris

Terazije has always raised many issues for urban planners. The problem can be boiled down to one question: is it a thoroughfare or a city square? Its shape is marked by its original purpose, with space for carts to pull off the roads to be repaired. Rather than having straight sides, Terazije is actually egg-shaped with bulging curves, adding to the sense that this is more than a space for traffic to pass through. Its width gives the feeling that it is waiting to be filled with a greater purpose. Knez Alexander Karađorđević decided that the old Turkish water tower was no longer a fitting marker for the new district and planned to replace it with a fountain. But he lost power before the monument was finished and the project was taken over by Miloš who completed it in 1860. The fountain is inscribed on all four sides with Miloš’s initials and the year of his second inauguration.

Terazije was given a face-lift in 1911 when a more decorative water feature was installed. The original was moved to Topčider and put next to the church and Miloš’s residence there, before being returned to its present position in 1975. As part of the same renovations the middle of the road was laid with lawns and flower beds, surrounded by an ornamental fence with elegant street lamps. It was, in effect, treated as a square with traffic allowed to pass down either side. Much thought was also given to the space between the two hotels, the Moskva and the Balkan, and how best to set off the view down to the Sava. After the First World War it was proposed that the gap be filled with a series of statues to celebrate the victory and commemorate those who fell in the conflict. Unfortunately, the sculptor produced an effigy of a naked man holding a sword and a hawk as the centrepiece of the arrangement, forcing a quick change of mind; the Victor was placed in its present position in Kalemegdan facing away from the centre of town.

After the Second World War the new regime introduced a different solution to the Terazije issue. They removed all the pre-war non-functional decorations, widened the pavements, pulled up the tram lines and replaced them with an overhead power supply for trolleybuses, turning it into the practical thoroughfare of today. The street now became an important point in the route of the annual May Day parade. This was a significant highlight in the calendar of communist Yugoslavia, an opportunity to put on display the latest technological developments, military hardware, and the support of the masses for the Party. Terazije maintained the theatrical purpose of a grand square, but without its stage props and scenery.

Terazije is now one of the city’s main traffic arteries connecting the central part of the old town to residential areas beyond. At the gap between the Moskva and the Balkan hotels is a junction of two roads. One goes to the right and down to the main bridge across the Sava to New Belgrade. This direction also links to the underpass that takes vehicles under Terazije and helps avoid congestion in the city centre. The other road is a steep hill, Balkan Street, leading to the railway and bus stations. The other side of Terazije has been closed off by the later addition of more modern buildings, reducing the sense of its open space. A little further down, the broad and imposing King Alexander Boulevard sweeps round and away from the main street.

At the crossroads is the Monument to the Patriots (Spomenik rodoljupcima) commemorating the Serbs who were hanged here by the German Army in 1941. The sight of the bodies swinging from the lamp posts was meant as a warning to others not to resist the armed occupation of the country. In the distance, above Slavija Square at the end of King Milan Street, rises the cupola of the massive St. Sava’s Church (Hram svetog Save), which stands on the plateau at Vračar, offering a towering presence visible down the length of both streets.

ROM

“A

LBANIA

”

TO

“M

OSCOW

”

The twelve-storey building known as the Albania Palace (Palata “Albanija”) dominates the bottom of Terazije. Before, a kafana with the name Albanija, built in typical Balkan style, occupied the site from the nineteenth century. It may not have been pretty to look at, but it was a firm favourite of its clientele. The playwright Branislav Nušić said of it in 1929:

There stands even today, as a reminder of old Belgrade, and will continue it seems for centuries, the kafana Albanija, a blot on the face of Belgrade, but El dorado to all its customers. There isn’t a kafana which spends less on its comforts and has more trade; nor is there one which has such a varied and mixed public.

Unfortunately, this view of its attractions was not shared by all, and for some years there was pressure on the city authorities to pull it down and replace it with something more appropriate. Urban planners and architects wanted a modern showpiece, which led to the Modernist design of the new Albania Palace in 1938. It was the tallest building in Yugoslavia and the iconic image of Belgrade, but stories circulated about the dangers were it to fall down. In fact, during the Allied bombing of the city in 1944 it was hit and damaged but was quickly and successfully repaired with no hint of it collapsing.

Between the Albania Palace and the Hotel Balkan is a fairly new block of shops and commercial premises built in 1964. No. 12 Terazije was the site of an old kafana, the Golden Cross (Zlatni krst), in which the first moving picture show was screened in Belgrade. A film industry appeared and grew very soon after this event. The Hotel Balkan on the corner is also a twentieth-century construction, from 1935, although there was an older hotel of the same name here for decades before. Across the road, the Hotel Moskva, or Moscow, was constructed in its monumental style between 1905 and 1907. Unfortunately, the house next door is not of the same distinctive architectural style and reduces the overall effect provided by the grandeur of the hotel.

Lena Jovičić, brought up in a bilingual home with her Serbian father and Scottish mother, describes Belgrade in the early part of the twentieth century in her book

Pages from Here and There in Serbia

(1926). She writes of the modernity of the Hotel Moskva:

The Belgrade of to-day is an agglomeration of Easter and Western ideas moulded and adapted to meet the requirements of this corner of the world. The contrast between the old and the new town is thus accentuated. Buildings of more than two or three stories high were few and far between in the beginning of this century, when the Hotel Moskva—so obviously Russian in design—seemed like a pelican in the wilderness. Twenty years have brought about many changes in Belgrade.

The progress that has been made since the work of reconstruction began in 1919 is little less than marvellous. In a remarkable short space of time new, modern buildings have been erected to take the place of those destroyed by the bombardment. On every hand there is evidence that Belgrade has risen like a Phoenix from her ashes.

The literary Phoenix involved the Moskva where, after the First World War, a group of artists, musicians, writers, poets and sundry bohemians began to meet in the kafana of the hotel. They did not form a coherent school or movement, but their meetings, discussions and polemics over the nature of art provided an engaging and stimulating atmosphere for a younger generation of Modernist writers amidst the Belgrade ruins. Miloš Crnjanski, Rastko Petrović, Momčilo Nastasijević and others cut their first literary teeth in this company.

A group of buildings on the wide pavement of Terazije beyond the Hotel Moskva are representative of Belgrade’s trajectory from a small Balkan town to a major European city. The Athens Palace (Palata “Atina”), at 28 Terazije, was built in 1902 as the family home of Đorđe Vučo, with commercial premises on the ground floor and living accommodation on the upper two storeys. It is an example of balance and harmony in an architectural design with features of the Italian neo-Renaissance set off by the two small cupolas on either side.

A somewhat earlier house, Krsmanovićeva palata, is at 34 Terazije, constructed about 1885 by Joca M. Marković but which he soon had to surrender to Aleksa Krsmanović because of a debt. Krsmanović lived here until his death in 1914. The front of the building facing Terazije is not in itself particularly remarkable, but behind the house is a large semi-circular terrace overlooking a family garden. Built on a slope, the house actually has two floors at the back—a feature not evident from street level. It has had many different owners and functions. At the end of the First World War, because of the extensive damage to both royal palaces, Alexander Karađorđević took up residence here. He proclaimed the unification of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in one state in the large reception room facing Terazije after which he gave a speech from the window to the crowd gathered outside. Between the two world wars the house was used by the Yugoslav Autoclub while the ground floor at the back was an exclusive shop selling oriental carpets. During the Second World War it became a canteen for officers of the German administration in Belgrade. After the war it was nationalized and used in turn as a youth centre, a diplomatic club, the offices for the government protocol section, and a bank.

The small but elegant structure at 40 Terazije was built in 1911 as a studio for the photographer Milan Jovanović (1863–1944), with his initials in relief above the entrance. His studio was on the first floor, the wall of which and most of the roof were all in glass, offering a very distinctive appearance from the main street at the time. Jovanović trained in Vienna and Paris before practising in Belgrade where he photographed a large number of famous people from the worlds of culture and politics.

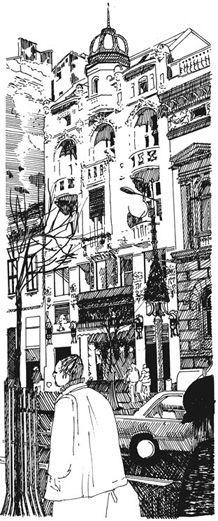

Across the road, the Ministry of Justice at 41 Terazije is an imposing administrative building from the 1880s, although the house next door at no. 39 is perhaps more interesting. This is the Smederevo Bank (Smederevska banka) from 1910 and offers the most distinctive design features in Terazije. It has a highly decorative façade in which the vertical lines in particular are emphasized. The eye moves naturally up this narrow threestorey house whose height is extended by the central cupola at the top. The balconies give a sense of greater depth, which fills out the vertical proportions of the design.

On the corner with King Alexander Boulevard rises the Igumanovljeva palata, named after Sime Andrejević Igumanov. Born in the southern town of Prizren, he founded a school in his home town which was to be supported by the rent from this building. He established other philanthropic foundations for education and children, and on the top of this building was placed a tall statue of him with children representing his legacy. The statue was removed in the 1960s when the city was more interested in updating its image and it was replaced by a neon advertising sign.

ING

M

ILAN

S

TREET

Terazije and King Milan Street together form a seamless flow, with the border between them marked by the colourful and highly decorated frontage of the Vuk Karadžić Foundation (Vukova zadužbina). The road was first known as the Kragujevac Highway (Kragujevački drum) when it was not much more than an elaborate and large cart track, muddy in winter and dusty in summer, until it was cobbled and planted with an avenue of chestnut trees. In 1872 it was called Knez Milan Street (Ulica kneza Milana), only to be re-christened in its present slightly different form in 1888 after Serbia’s recognition as a kingdom. The communists changed the street in 1946 to Marshal Tito Street (Ulica Maršala Tita), which it stayed until the end of the communist system when it received the title Street of Serbian Rulers (Ulica srpskih vladara) in 1991. The new name, however, lacked the kind of commemorative or memorable ring expected of a capital city’s central thoroughfare. It was felt that the old name offered a specific historical reference and a complement to the other monarchs’ monikers in the city centre, so it reverted back in 1997.

At the beginning of King Milan Street is the red and white façade of the Vuk Karadžić Foundation. The house was constructed in 1871–72 for the judge Dimitrije Golubović but did not remain long in his possession as it was used as the Russian Consulate prior to being bought by the Ministry of Education in 1879. It remained in the ministry’s hands for over a hundred years until it became the office for the Vuk Karadžić Foundation, an organization which continues to promote his name and to work for the development of the Serbian language. The building also houses the Institute for Literature and Art (Institut za književnost i umetnost) funded by the government to conduct research in these areas. The building was given its distinctive exterior during renovations in 1912, with a heavy wooden door, dark red decoration and elongated windows on the first floor as a modern interpretation of a traditional Byzantine church design. Further down and across the street, next to the palace complex, is a small side street with a water cascade down the centre. This is Andrić Crescent, named after the winner of the Nobel Prize for literature Ivo Andrić, where there is a statue to the writer. There is now a museum at no. 8 in the flat where he lived for the last years of his life.