Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (80 page)

Â

Â

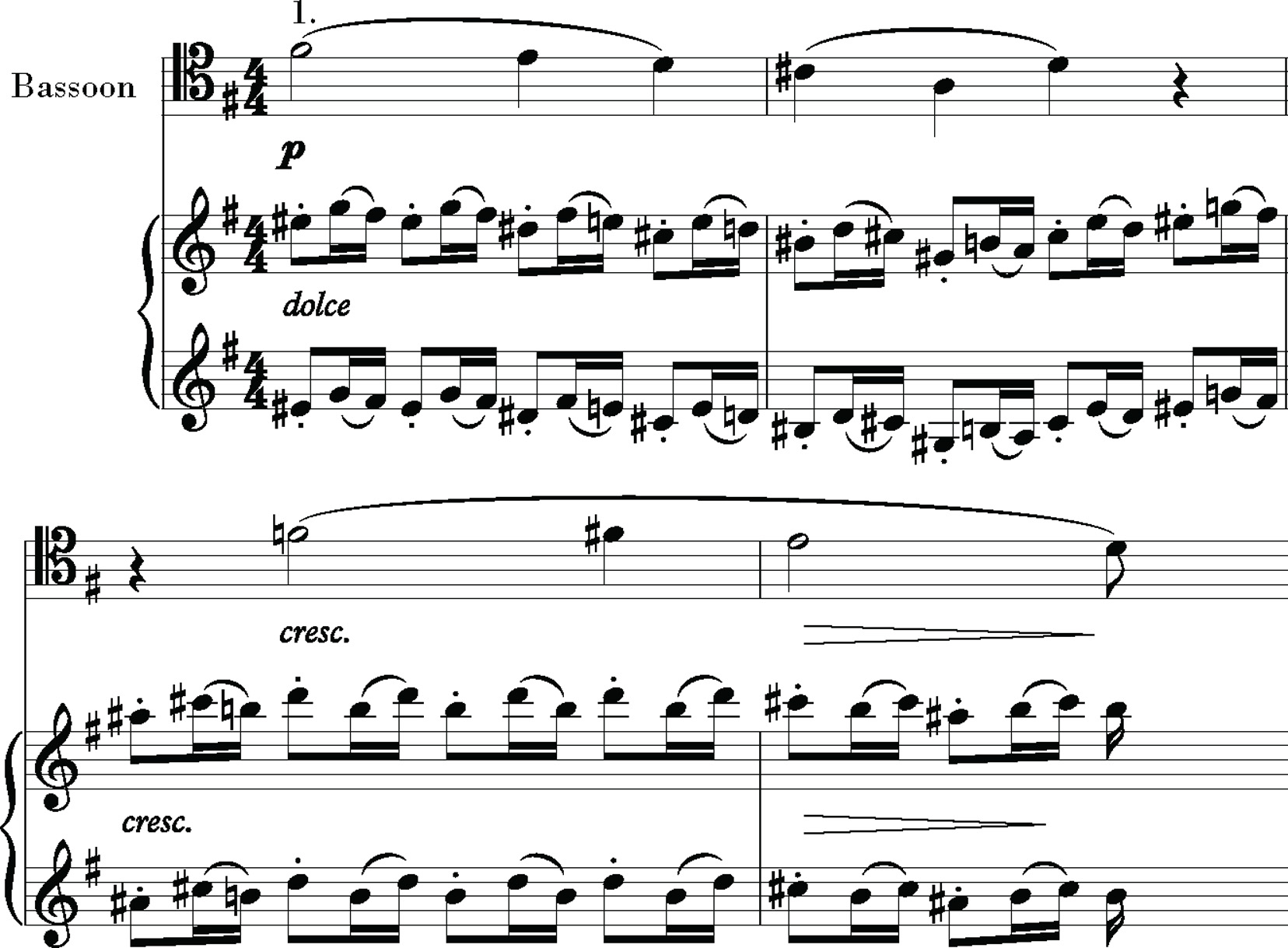

Soon after, while the bassoon plays a lyrical line, the piano surrounds him in mocking dissonances:

Â

Â

Throughout this game the overall tone is stately, lyrical, only occasionally military. The orchestra's exposition does fall into a tranquil and lovely interlude in B-flat that the piano succumbs to later. During the development there is no particular hostility between the forces, but suddenly at the recapitulation the soloist bursts out Â

fortissimo

with his original version of

das Thema

, which has not been heard since the opening soliloquy. It is as if he were shouting,

No! This is the way it goes! This is my idea that you stole and never got right!

8

Then the piano retreats to

pianissimo

, the tension ebbs, the combatants return to their places, and the exact solo version of the

Thema

disappears again. In the cadenza the soloist must work hard to outdo all the virtuosity that has preceded it.

9

The coda builds to a grand

fortissimo

finish, the soloist joining the massive chords of the close.

The rift between solo and orchestra comes to a head in the E-minor second movement: alternating phrases, never together, the orchestra insistent, the soloist oblivious, inward, lost in some kind of

raptus

âbut also calming and cajoling. While the basis of this dramatic tableau is simple enough, there had never been anything like it, because its fundamental conception negates the very idea of unity of affect and material. At the beginning the strings play a quiet, dotted military figure, ending on a harmonically open note: an invitation. Then, silence. The soloist responds quietly,

molto cantabile

, as if singing to himself. He has returned to the chordal texture and the brooding tone of his soliloquy that opened the piece. As in the first movement, he is not interested in the military tread that the strings try to force on him in phrases of mounting belligerence. The soloist sighs, retreats, breaks out in roulades, screams tritones (AâD-sharp) in a small cadenza. The strings retreat with a last marching tread,

pianissimo

, then slide into a sigh much like the soloist's. He echoes it. With that the movement ends, if not in resolution, then in some kind of truce.

10

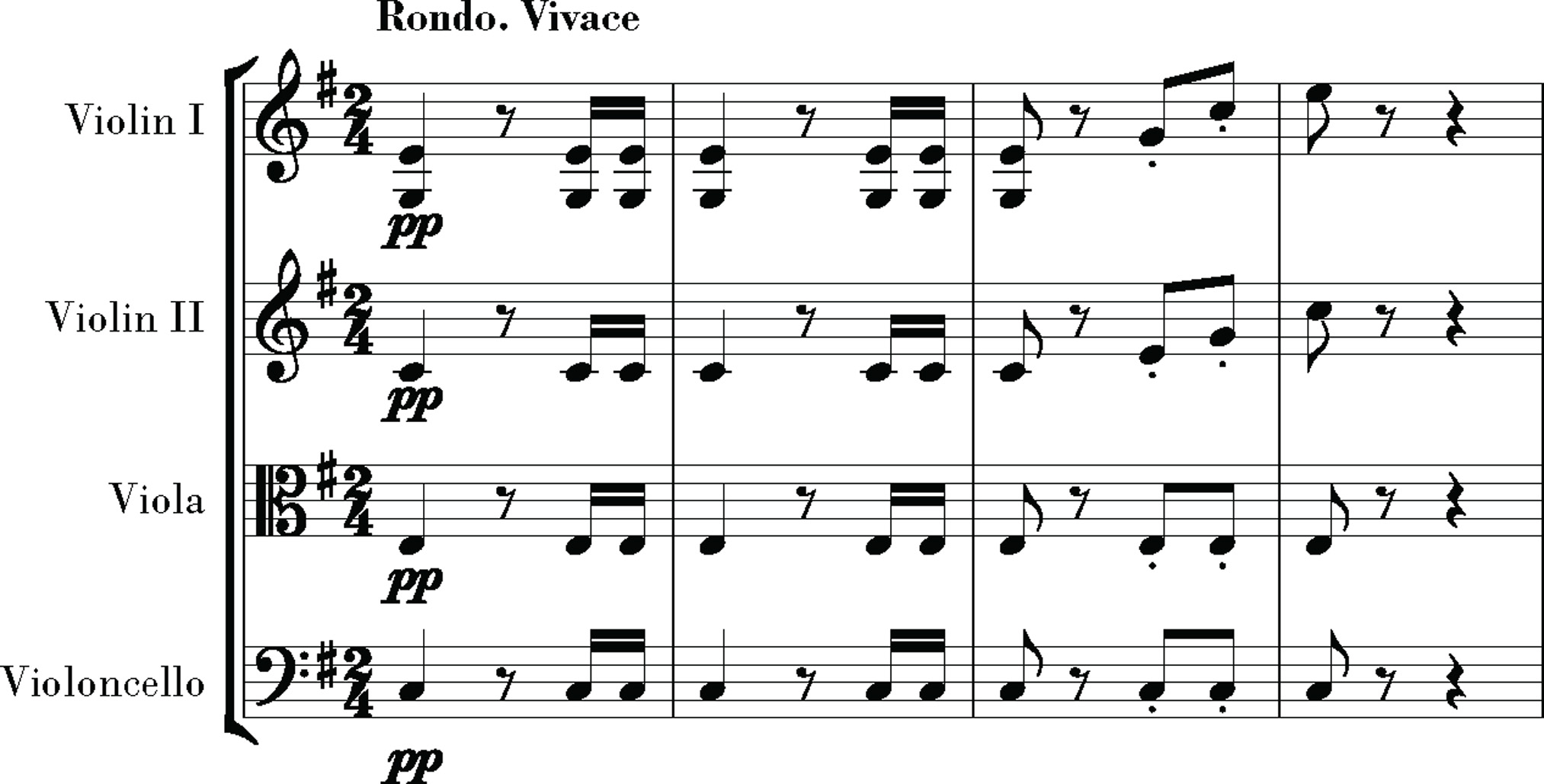

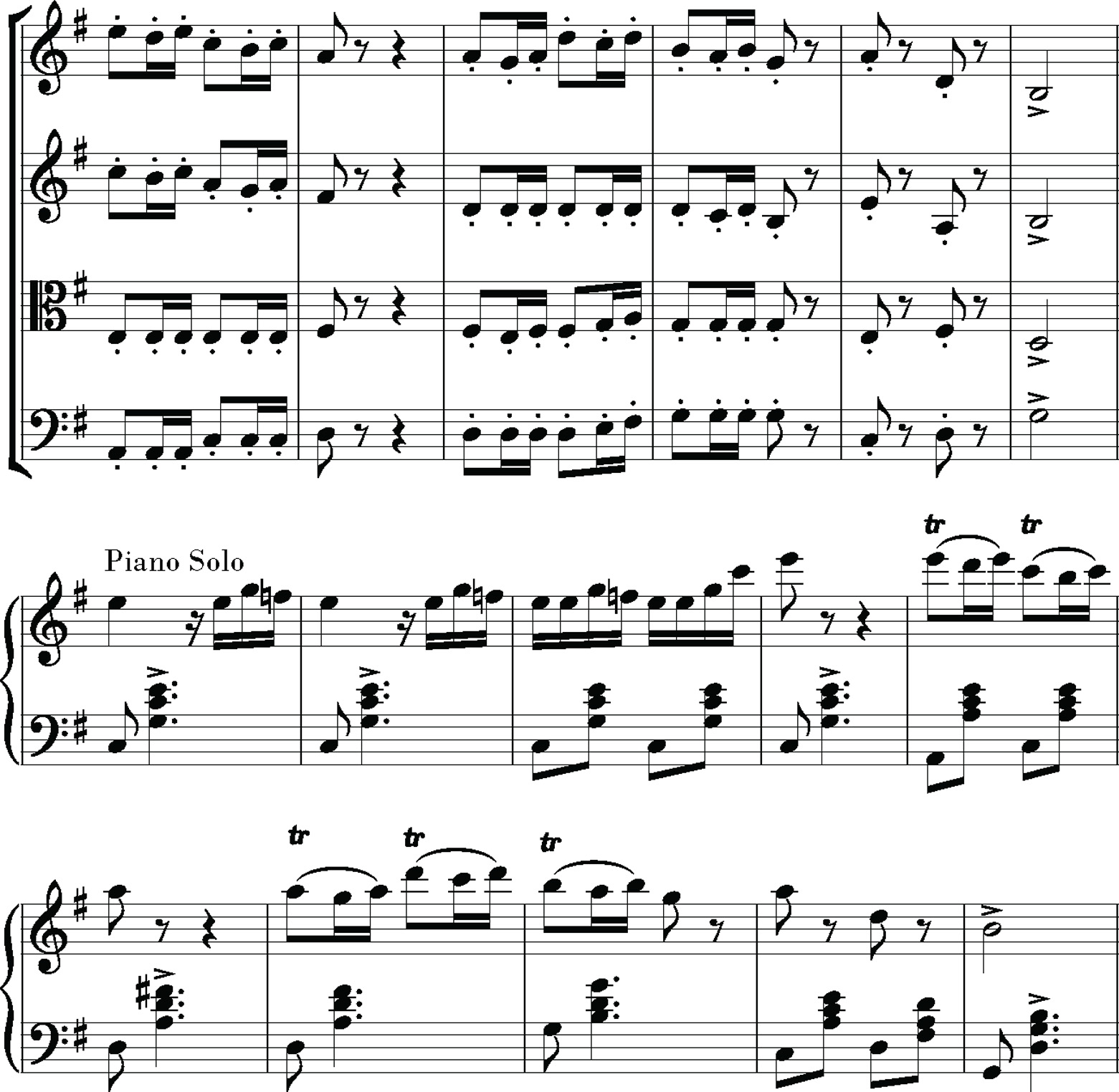

In the beginning of the concerto, the strings first entered on the not-quite-right piano theme, in the wrong key. The strings kick off the Vivace finale with a dashing rondo theme again in the wrong key, C major. It also happens to be a tune that the soloist cannot play: a piano is not capable of comfortably executing those fast repeating notes that are natural for a bowed instrument. Echoing the theme, all he can do is turn it into a piano version:

Â

Â

Â

In other words, topsy-turvy. In the first movement the strings can't get the piano theme right; in the finale the piano can't precisely play the string's rondo theme at all. In the slow movement the two forces reach a tentative rapprochement only in the last bars. In the finale the original rivalry endures, the sense of call-and-unreliable-response, but now the game is played as comedy. By the third line the strings even present a coy little bit that the piano

can

play exactly. The piano is back to its glitter-and-be-gay mood, but now there is a sense that the two forces are completing one another's thoughts rather than contradicting them. The piano presents a beautifully lyrical B theme that the strings gently second. Still, the music has a lot of trouble settling on the actual key, G major, until the final appearance of the flowing B theme, and that long-delayed resolution gives the moment a throat-grabbing poignancy. In the coda the A theme insists on coming back in C major but finally agrees to end in the proper key, G.

One of the striking qualities of the Fourth, eventually to be numbered among the finest of all concertos, is that its disputes, its debates, its mutual lacks of understanding, whatever one wants to call them, are carried on in the outer movements largely in a tone of play, most playfully in the finale. And the finale's denouement comes well before the coda, in a sudden and sublime stretch of singing E-flat major,

pianissimo

, in divided violas, with gentle piano garlands above. It is as if piano and orchestra have decided together that wrong keys are a fine thing.

11

Â

It is hard to conceive what that first audience in 1808 made of the Fifth Symphony in C Minor, op. 67, as they sat shivering in the cold theater having already heard nearly two hours of scrambling performances of new and strenuous music. How many listeners heard an epoch beginning at the first performance of the

Eroica

? Something of nearly that order was happening again. By comparison to the Fifth Symphony, the Third is almost esoteric. The Fifth reaches out and shakes you, then for solace presents you with the most exquisite beauties.

The Third Symphony is in E-flat major, to Beethoven most often meaning an echt-Aufklärung, humanistic, heroic piece (though he explored other moods of that key).

12

The Fifth is in C minor, therefore driving, portentous, fateful. First conceived and sketched in the same burst of creative fire as the

Eroica

, the Fifth unfolds in a different world from that of the Third, but it has the same kind of dramatic narrative.

Only this time Beethoven did not give a name to the story. At some early point in the sketching, he decided on or sensed something like this:

The C Minor Symphony will be more unified in its narrative and in its material than any symphony before, beyond anything I or anybody else has done

.

The essence of that unity will be conveyed by the simplest thing possible: a four-note tattoo, a primal rhythm. That rhythm will saturate the first movement and return in new guises to the end. How the motif is transformed will be the essence of the narrative. So the leading idea will be not a “theme” but a motif. And I will treat that tiny motif in the same way I treat any opening theme: everything will flow from it

.

Later Beethoven's amanuensis Anton Schindler told the world that Beethoven said of the symphony's opening thunderclap,

Thus fate knocks at the door

. Beethoven was excruciatingly familiar with that knock. But Schindler was a chronic liar, and there is no way to know whether Beethoven truly said that (assuming that, now and then, Schindler uttered something true). At the same time, Schindler was an accomplished musician and what he said about Beethoven's music was often astute, whether factual or not. Which is to say that here Schindler was right: the first movement implies a story about something on the order of the action of fate on the life of an individual, an assault that cannot be turned back but can only be borne, resisted, transcended from within.

13

So in Beethoven's mind there was presumably some dramatic scenario behind the Fifth Symphony, but he decided that, like most of his works, this one did not need to be nailed to a stated narrative. For those equipped to understand it, the gist would be clear enough in the notes. That story would be as direct as the rest of the symphony: a movement from darkness to light, from C minor to C major, from the battering of fate to joyous triumph.

The compaction of material flows from the first gesture, that unforgettable explosion of three Gs and an E-flat. Once again, for Beethoven the opening idea,

das Thema

, is the embryo of a work. Here he boils down

das

Thema

to just four notes that still function like a

Thema:

they are the symphony in essence.

Â

Â

In the symphony's first moment, in that percussive

da-da-da-dum

, we hear the primal rhythmic figure that will dominate the first movement and persist as motif and rhythmic scaffolding to the end. We sense the force-of-nature energy of the movement. We hear the bluntness of effect, the simplest harmonies proclaimed as if discovered for the first time. We hear the muscular quality that will mark the orchestral sound. We are misled by the key; it seems to be E-flat major but is actually C minor; that ambiguity creates tension.

14

The propulsive effect of the primal “&-2-& 1” rhythmic tattoo comes from its beginning on a void, a charged rest on the beginning of the 2/4 measure, then three eighth notes driving into the next measure, in which a new start of the figure is usually overlapped to drive forward again. Call the effect of this tattoo dominating the movement a

monorhythm

.

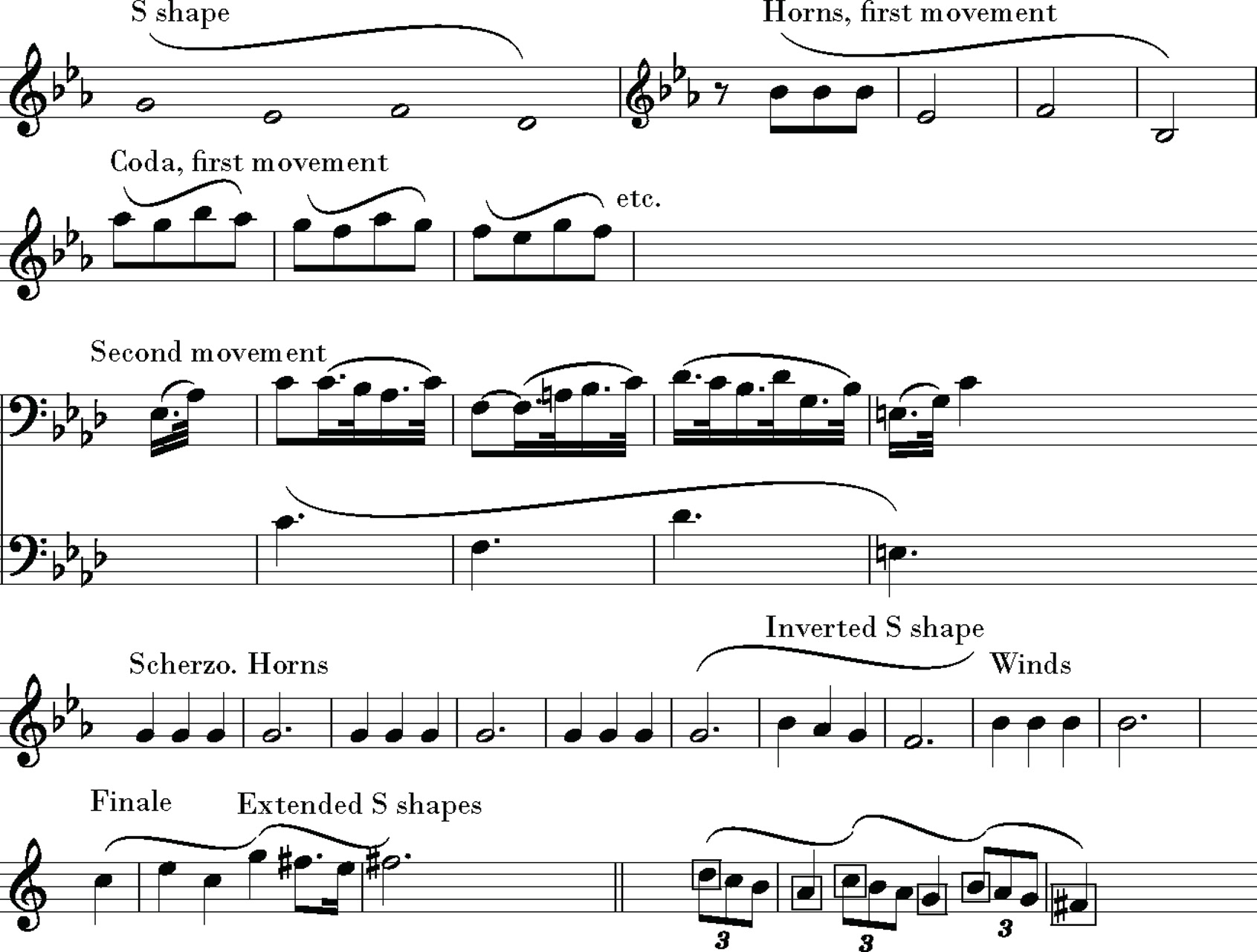

At the same time, besides that dominating rhythmic motif, we are presented with a more subtle undercurrent: the opening pitches GâE-flatâFâD form an S shape, down-up-down, that will serve as scaffolding for all the themes in the symphony.

15

Â