Read Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future Online

Authors: Fariborz Ghadar

Becoming American: Why Immigration Is Good for Our Nation's Future (30 page)

While Amsalem talks wistfully about his birthplace in Algeria, he quickly adds that his country, as he knew it, has disappeared like a number of other countries, such as Syria, Iran, Egypt, and Lebanon, which have been buffeted by war and sectarian violence and where an element of society has been eliminated. He believes that the United States’ strength is its diversity and its tolerance, allowing so many different people, many of them “refugees” from other countries, to develop their particular skills and to contribute them to the common good. He hopes the virtues of tolerance and respect ultimately win out over intolerance and bigotry.

A Certain People: American Jews and Their Lives Today

by Charles Silberman, 1985:

American Jews are committed to cultural tolerance because of their belief, one firmly rooted in history, that Jews are safe only in a society acceptant of a wide range of attitudes and behaviors, as well as a diversity of religious and ethnic groups.

The message he has passed onto his children, in addition to a strong emphasis on the value of education, is that the onus for their future is squarely on them. The example is clear: America gives most an opportunity to forge their own path, and those who take advantage of such an opportunity ultimately succeed.

22

Can You Go Home Again?

A

significant number of students and others who are in the United States studying technology, science, and engineering, and who would absolutely love to work here, are going to have to go back home. The fact is we’re driving a chunk of people out of the country who have skills very much in demand.

These immigrants are the same ones who will be instrumental in developing the future-oriented industries vital for the United States to lay claim to in order to have continued global economic success. Future-oriented industries that form clusters, such as nanotechnology, biotechnology, robotics, and shale oil and gas, will be nurtured somewhere around the world, and if we don’t allow the potential innovators in these industries to remain in the United States, we cannot expect to be a default leader in the competition of global economies.

Case in point: Each year the United States provides four hundred thousand visas to foreign-born students to study at American colleges and universities, and then our current immigration laws force them to leave the country upon graduation, thereby becoming our competition.

1

For the Harvard Class of 2016, foreign citizens, U.S. dual citizens, and U.S. permanent residents together make up more than 19 percent of the class, representing eighty-six countries. So what are their options after graduating?

Currently there are more than a million temporary workers and students in the skilled-worker immigration categories waiting for a yearly allocation of 120,000 permanent resident visas.

2

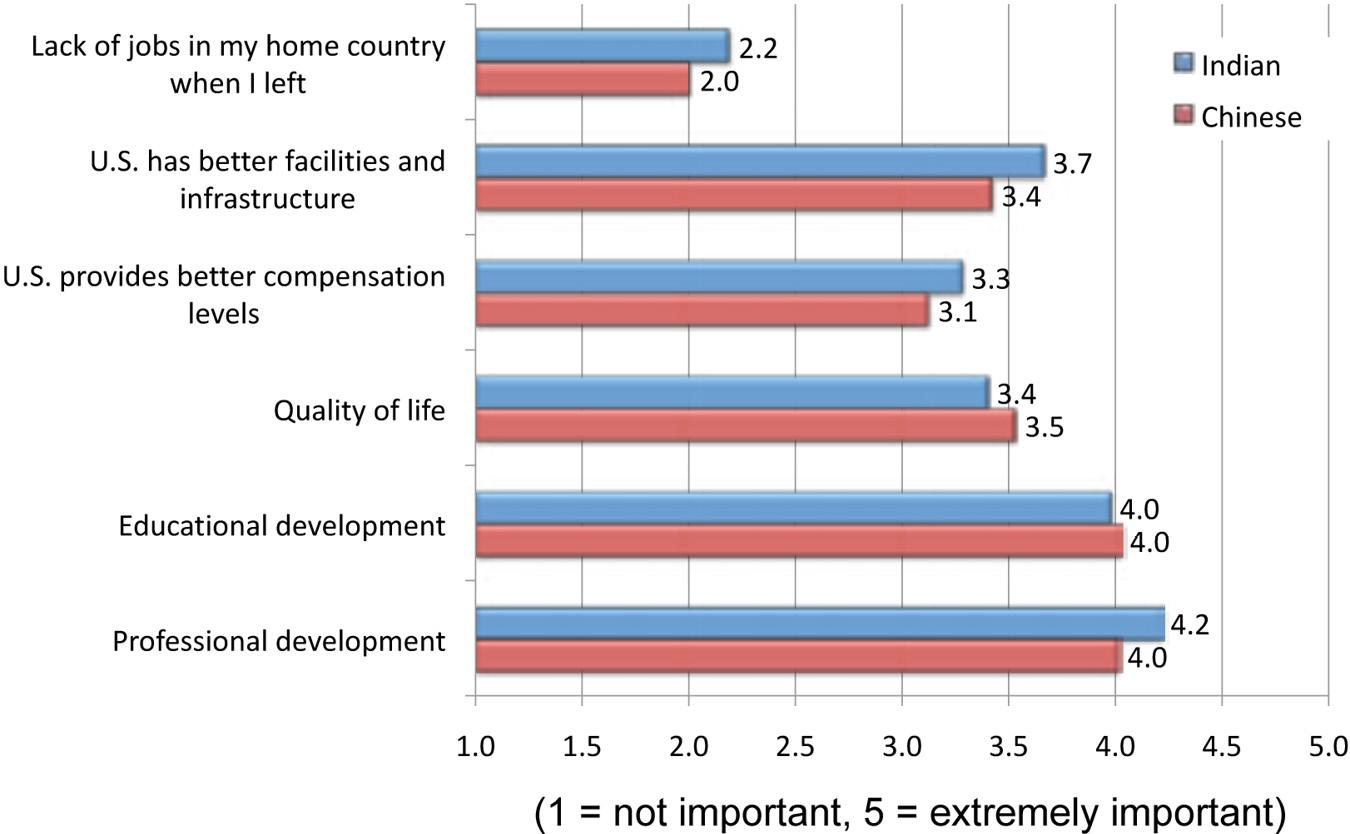

Indian and Chinese immigrants who had worked or received their education in the United States and had returned to their home country were asked to rate why they had initially decided to come to the United States. The table above illustrates that the type of motivation for their coming to America was certainly one of betterment of themselves, which would in turn have enriched our society.

Average Rating of Factors Contributing to Decision to Migrate to the United States

Vivek Wadhwa, AnnaLee Saxenian, Richard Freeman, Gary Gereffi, and Alex Salkever, “America’s Loss Is the World’s Gain: America’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs, Part IV,” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, March 2009,

www.kauffman.org/uploadedfiles/americas_loss.pdf

.

Virtually every industrialized country will be confronted with a significant labor shortage, particularly in the knowledge sectors. This is exacerbated by aging (retiring) populations and low birthrates, particularly in Japan, Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia. Japan hasn’t responded to it; the population is homogenous and xenophobic, and even though its population peaked in 2006, in terms of allowing immigration or encouraging it, it’s just not part of the country’s makeup. Europe is also in a decidedly negative position. Its nation-states, with their homogeneous (or at best two culture states, think Switzerland), have a built-in knee-jerk reaction to immigration and the foreigner in general. Because Europe has such a different history than the United States, which was founded by immigrants, countries there are even less inclined to accept those who are culturally, ethnically, or religiously different than themselves. Immigration, therefore, remains a politically touchy subject and a rallying cry for extremist parties, due to issues with integration into these relatively insular societies. To boost their birthrates, European nations have implemented policies that reward families who have children via tax incentives and increased maternity leave. But it is doubtful that these policies will suffice to staunch Europe’s population decline.

Germany has been somewhat more open, particularly after World War II, when it lost a generation of young men. In 1961, it signed a labor recruitment agreement with Turkey, encouraging large numbers to immigrate as (mainly unskilled) guest workers. However, they were viewed only as guests who were expected to eventually leave, and little effort was made to successfully integrate them into society.

The companies that suffer the most from this are the smaller leading-edge companies in science, technology, and innovation, companies that really rely on brainpower. According to “Tech Firms Go Abroad to Hire,” published in

USA Today

, there has been a recent surge in these companies hiring abroad because the United States no longer provides the best brainpower. These companies are no longer taking jobs overseas for cheaper labor, like some may speculate; rather, they are looking for brighter talent.

3

A study by Roger Marting and Richard Florida found that creative jobs requiring highly skilled talent have grown from 10 percent of the economy to more than 30 percent. Filling these creative opportunities represents a new economic opportunity. While talented immigrants created 52 percent of Silicon Valley’s companies, today many are leaving thanks to immigration policies that have made it harder to stay in the United States.

A further shift toward Thomas Friedman’s comparison of the historical change in options for the “B” student from Bethesda and the genius in Bangalore is that, nowadays, if you are that genius in Bangalore, “you no longer need to emigrate to innovate.”

For example, former chief data officer at Yahoo!, Usama Fayyad, came home to Jordan convinced there was enough raw material to create an Arab “Silicon Wadi.” He is now a part of Oasis500, an Arab-owned high-tech accelerator, looking to nurture four hundred new startups in Jordan.

Experts are even seeing a new trend in which ambitious American children of immigrant parents are returning to their country of origin because they see greater opportunities abroad.

4

Those countries are seeing immigration as an integral part of their national economic strategy and have responded by making employment, investment, visa, and tax incentives available to those who make the move. However, this is a phenomenon best suited to the younger generation, as it is doubtful that many fifty-plus-year-old immigrants would be equipped to deal with this new occurrence.

My own original return to my native country was at the age of about seven years old. My parents had finished their university studies, and so along with my sister, the four of us took a freighter from Louisiana to Casablanca. We were unable to afford better transport, as the currency situation in Iran meant that we were only able to rely upon what my parents had been earning by working, while my father was also attending school.

The culture shock of that trip got incrementally greater each stop we made. I had become quite Americanized by this point, and leaving the southern United States and arriving in Casablanca presented a whole different landscape of people, sights, and smells. From here we went to Beirut, which was quite untouched by the Western world at that time, and then onward by car to Tehran. I was now fully down the rabbit hole.

While we had been in the United States, our social circle consisted of the four of us, and a few other international students. Now, back in Tehran, we were immediately welcomed into a large extended family that had an active social and cultural life.

I can still fondly recall the monthly gatherings at my grandmother’s beautiful house. As the matriarch, she would invite the local Mullah over in order to say prayers (Rouzeh khanney), and it would turn into an all-day family event.

On the floors were large rugs and various smaller ones scattered on top. Huge cushions and pillows were neatly arranged in order to facilitate conversation. There was a beautiful silver samovar with a set of Iranian teacups, along with rice cookies or sweets. The men were separate, chanting, while the women, dressed in their black chadors, were crying. The children were given free reign to play all over the garden, and after the Mullah left, refreshments were consumed, connections reestablished, and contacts made.

This picture is unlikely to exist today in the same way it did for me back in the 1950s. While there are still cultural differences quite apparent today, the likelihood that there will be a common cultural lexicon upon which one can draw makes it all the easier for an immigrant to reacclimate back into his or her society.

However, for immigrants who have been here for a few years and to some extent have assimilated into the U.S. culture, returning to the old country may have a romantic attraction, but the reality is much different. Both the immigrants and their countries of origin have evolved in different ways. There are often new political environments, loyalties, and cultures, and while returning may seem ideal on the surface, it is in fact difficult, for many immigrants have already assimilated into an entirely different culture.

My return to Iran is impossible, for Iran has changed. It is less Western, more religious, and much more repressive. Heawon Park also faces a similar situation; she has become an Americanized woman of Korean decent. The younger generation and the graduating students, who have arrived more recently, however, see their country of origin as one without many changes. They, therefore, might have a much better chance of actually returning.

Now that the United States is no longer the only place where talented people can put their skills to work, there should be a wakeup call that immigrants have a plethora of never-before-seen options at their disposal. Brain drain no longer occurs in only one direction; the United States cannot afford to rest on her past laurels.

NOTES

1. “Building a 21st Century Immigration System,”

White House

, May 2011,

www .whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/immigration_blueprint.pdf

(accessed July 1, 2013).

2. Vivek Wadhwa, AnnaLee Saxenian, Richard Freeman, Gary Gereffi, and Alex Salkever, “America’s Loss Is the World’s Gain: America’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs, Part IV,” Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation,

www.kauffman.org/uploaded files/americas_loss.pdf

(accessed July 1, 2013).

3. John Shinal, “Tech Firms Go Abroad to Hire,”

USA Today

, June 5, 2013,

http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/MONEY/usaedition/2013-07-05-Silicon-Valley -not-waiting-for-US-immigration-reform_ST_U.htm

(accessed August 18, 2013).

4. Kirk Semple, “More U.S. Immigrants’ Children Seek American Dream Abroad,”

New York Times

, April 15, 2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/16/us/more-us-children-of-immigrants-are-leaving-us.html?pagewanted=all

(accessed July 8, 2013).

23

Lessons for the Next Generation

C

hildren of immigrants to the United States learned from watching their parents work hard at making something of their lives in a country offering a chance to succeed. Many of them carried on to achieve great things, like my daughter Otessa, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Yoon-shik Park and their respective children. They did so in part to give something back to the country that allowed them and their parents the chance for a better life.