Batavia (5 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

Only shortly after taking up his tenure as Governor-General in 1618, Coen became convinced that the time was right to move the VOC headquarters in the East Indies from the cesspit of Bantam to Jacatra. At this time, Jacatra was a small settlement on a big harbour that lay 50 miles to the east of Bantam, on a low plain on the north-western tip of Java, where eight years earlier the Company had built a small warehouse.

On 30 May 1619, Governor-General Coen led a fleet of 16 vessels and 1200 men to attack Jacatra. Typically, the thin-lipped one displayed no mercy. Leading from the front, Coen took his men ashore against a native population that might have outnumbered them by three to one but were no match for them in terms of either firepower or viciousness. And nor was there anything that the few remaining English could even

begin

to do to stop them.

By battle’s end two days later, hundreds of the locals lay dead, their buildings and fortifications, including the palace of the Pangeran of Jacatra, razed, with the Dutch now in total control of the port. In his report back to the

Heeren XVII

, Coen was exultant:

Click Here

But Coen, who now considered the Dutch nothing less than ‘the

lords of the land of Java

’, had little interest in establishing friendly relations with anyone, and in terms of assaults on the local populace he had not yet fully broken into stride.

In early 1621, the population of the Banda Islands, where the most lucrative of the spices grew, stood at about 15,000 happy natives, with a small sprinkling of Dutch officials of the VOC and other merchants from Java, England, Portugal, China and Arabia who lived there and helped organise trade.

Coen decided to crush them, and the first that the people of Lonthoir Island in the Bandas knew of his intent was on 21 February 1621, when 13 ships suddenly appeared off their shores and one of them began circling the island, apparently examining the defences and looking for the best spot to attack.

On the morning of 11 March 1621, Coen personally directed his 1500 Dutch soldiers – together with 80 mercenary samurai warriors he had hired from Japan for the purpose – where to land. In next to no time, they had swarmed ashore at a half-dozen different spots and were climbing the cliffs and attacking the Bandanese from all sides.

Though the Bandanese fought hard, in the end they simply had no answer. They surrendered the very day after the attack, but that did not mean the butchery ceased.

Even the

Heeren XVII

were appalled when they found out about the level of savagery Coen subsequently pursued, sending him an official rebuke, albeit together with 3000 guilders as reward for having secured the islands. However, those executions were just the beginning, a first few speckles of the rain of blood that would fall when the wholesale slaughter began.

By the end of the Dutch campaign in those islands, the entire native population had been all but wiped out, with just a thousand or so surviving. Most of these were only kept alive so they could be used as forced labour on the nutmeg groves, labour that actually knew something about how to cultivate the island’s half-million nutmeg trees.

The Governor-General’s focus was now on making his newly conquered islands as productive as possible, and the land on the islands of Lonthoir, Ai and Neira was divided up into 68 separate estates.

Though the settlers from the Netherlands never quite arrived in the numbers that were hoped for, still there were enough to make the system work. Dutch immigrants were paid

1

⁄ 122 of the price that the nutmeg brought in the markets in Amsterdam, yet they still managed to make a handsome living, notwithstanding a lifestyle so dissolute it was said of them that ‘they

begin their day with gin and tobacco

and end it with tobacco and gin’.

As to female companionship, they did not lack it. As detailed by Charles Corn in his book

The Scents of Eden

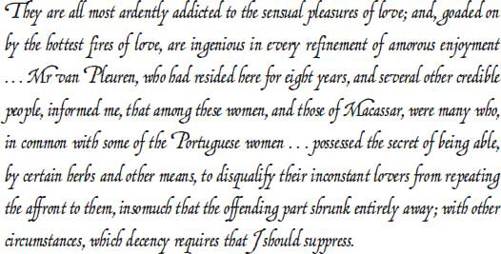

, though there was a strict rule against marrying local women without the governor’s consent – on pain of being whipped at the flogging post in the public square – there were ways around that. One was to have a comely slave girl baptised as a Christian, in which case the governor would likely give his permission for marriage. The other, far more popular, method was to help yourself anyway, without parading your girl in public. Either way, the settlers were admirers of the women, particularly the Bugis women who hailed from the nearby island of Celebes. One settler memorably wrote of these olive-skinned beauties:

Click Here

Yes, for the new settlers, you

could

argue with the VOC about the price of spices, but not for too long – there were plenty of other things to keep you busy, provided you remained ‘constant’.

Meanwhile, other natives who had survived the war for the Spice Islands had been sent to Jacatra to act as forced labour on the settlement that Coen was furiously reconstructing on the ashes of the Javanese settlement his troops had razed in 1619. Coen named his new centre of trade in the Dutch East Indies ‘Batavia’, after the famed Germanic tribe the Batavians, who were the ancestors of the Dutch. (It was the stuff of myth and legend how this warrior race of Batavians had thrown off the shackles of the Roman occupation in the Netherlands and

crushed

their oppressors. The Dutch identified with their own efforts to free themselves of Spanish rule.)

Coen’s first measure after occupying Jacatra and marshalling the necessary labour was to have an enormous 24-foot-high stone wall constructed around where he planned to build a fortified citadel overlooking the harbour and a new town immediately behind it to the south. The inclusion of guarded gates and well-manned bulwarks across the citadel’s and the town’s perimeter walls at regular intervals would help ensure no one unlawfully entered or exited either precinct.

For added protection, a series of canals was dug around the entire perimeter of both the citadel and the settlement. So great was the amount of wealth envisaged to flow through the trade centre that six fortresses were to be constructed throughout Batavia to safeguard the VOC coffers.

Offshoots of the Jacatra River, 180 feet broad and flowing from south to north alongside the western wall of the settlement, enabled many additional tree-lined canals to be built within the town, making for a veritable miniature Amsterdam by the sea, the canals being an adjunct to the paved dead-straight streets that criss-crossed the burgeoning metropolis. Beside those streets, some 3000 narrow, tall houses and warehouses were built – all of them stuccoed brick, designed in the classic Dutch fashion – along with the odd tavern, church and school.

The dominant feature of the landscape was the massive, all-but-impregnable citadel. The political, financial and military nerve centre of the VOC’s entire East Indies spice-trade operation, at either of its four corners stood four towering bulwarks – named the Pearl, Ruby, Diamond and Sapphire – generously armed with cannons. One enormous gated entrance, the Water Gate, was constructed on its northern side facing the sea, while the Land Gate on the southern side faced the settlement, the only access being across a 14-arch bridge spanning the canal.

The intrusion of the Dutch into Java and their naked occupation of the land had enraged the wider population and its leaders. For his part, the Sultan of Mataram – the local ruler who controlled the eastern three-quarters of Java and had ambitions of uniting all the island under his own rule – had not minded, particularly, that Coen’s men had wiped out the wretched Moluccans, but the fact that the Dutch had dug in at Batavia was an outrage.

Unless the Sultan of Mataram could mass his forces and wrest back Batavia, Dutch control over all of the Spice Islands was now complete.

True, they did not have the same control of the northern Moluccan islands of Ternate and Tidore as they did of Ambon, but to make sure those islands provided no competition they stormed ashore just long enough to cut down every clove tree on them and proclaim that anyone caught growing one thereafter would be put to death. Henceforth, they would allow the production of cloves only on Ambon and instituted a system whereby the head of each Ambonese family had to be responsible for the planting and

maintenance of ten clove trees

.

With the subjugation of the Spice Islands and the building of Batavia, the Dutch had gone from being a major trading partner in the East Indies to nothing less than the sole, supreme occupying power.

The VOC’s rise was matched by that of many of its officials, and none more so than Francisco Pelsaert, whose upward trajectory through the ranks had been so startlingly rapid as to be almost without precedent. Testament to Pelsaert’s abilities, all of his recommendations had been accepted, trade and profits had expanded commensurately, and where there had once been a bare patch of dirt at Agra now stood an enormous VOC trading station. His salary had increased almost tenfold, from the mere 24 guilders a month when he had joined the VOC over a decade earlier all the way up to 200 guilders a month now. If he had not found a wife into the bargain, still, like many of the traders living in foreign climes, he had been able to enjoy the charms of many of the local women and even, on occasion,

women of the Moghul nobles

.

Not quite everyone was in his thrall

, however, and a case in point occurred in mid-December 1627, shortly after he boarded the good ship

Dordrecht

in the Indian harbour of Swally, near Surat, to head back to Amsterdam. At this point, Pelsaert was entirely depleted after a stretch away from home now into its tenth year, and also ill, having contracted malaria. Though India had been the place where his career had taken off, he had vowed never to return to tropical climes, so exhausting did he find it, so ghastly did he feel.

The

schipper

, skipper, of the

Dordrecht

, Ariaen Jacobsz, was an enormous, rakish mariner who hailed from a small fishing village named Durgerdam, which was near Amsterdam. As it turned out, he and Pelsaert took a dislike to each other with an instantaneity matched only by its intensity, which started when Pelsaert expressed his fierce outrage upon discovering that Jacobsz was engaging in private commerce. That was

strictly

forbidden by the VOC and had to cease immediately! And yet that really was only the beginning. For although circumstance had brought them tightly together, they were a study in opposites that did

not

attract . . .

Pelsaert, a refined, diminutive man with a passion for music, had roughly the same physical proportions as Jacobsz’s left leg. While Pelsaert was a creature of the Company and gloried in the fact that he had risen so high among its official elite, Jacobsz’s principal passion was whoring and he had no particular loyalty to anything – certainly not to high VOC officials, whom he hated as a matter of principle. Jacobsz was friends with men known around the bars and brothels of Amsterdam by names such as

‘Scarface’ and ‘Hook’

. If he had any artistic side, it was evident only in the creative way he rearranged the physical features of other men’s faces, while they often did the same to him, just before they died.