Batavia (33 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

‘And,’ Jeronimus says softly in conspiratorial tones, as they all lean forward to catch every word, ‘I’ll tell you how we’re going to do it . . .’

6 July 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

To the broad mass of people on the island, Jeronimus seems to have softened somewhat. On this morning, he announces that he wants people to join Hayes and his men in his search for water and is even happy to provide the vessels so they can be dropped off there. There are many keen volunteers.

In this first instance, Zevanck, with six of the strongest men, including Lenart van Os and Mattys Beer, immediately takes four of the lucky survivors – Hendrick Jansz, Thomas Wensel, Jan Cornelisz of Amersvoort and Andries Liebent – with their personal effects, out on the raft towards the High Islands. The four men are thrilled to have been selected. Despite the suddenly soothing words of Jeronimus, the fact is that three men, Hendricxsz, Roelofsz and Dircxsz, have met their violent deaths in the last 24 hours at his insistence. And,

while Ariaen Ariaensz seems to have somehow miraculously escaped

, or at least disappeared, that doesn’t change the common feeling. That is, if there is a chance to get to the High Islands – which are about as far away as it is possible to get from Jeronimus in the short term – then surely it has to be a chance worth taking.

Their raft duly travels along the deepwater channel, right to the lip of Seals’ Island, and then veers to the north towards the High Islands, taking them out of the line of sight of those who might be watching their progress from Batavia’s Graveyard. Then, things seem suddenly strange to the four men. Zevanck and his men, who have been chatting happily, suddenly stop talking. Despite the sunny day, a chill wind has begun to blow. And then something as stunning as it is frightening happens. At a nod from Zevanck, the six men suddenly fall upon the four men, and although the raft rocks violently, they soon have them trussed up like chickens ready for roasting. With their hands and legs tied tightly together, they are entirely helpless.

What now?

They don’t have to wait long to find out.

Upon a thin-lipped nod from Zevanck, the first three men are tossed overboard, and after just a little violent shuddering they disappear from view, as their lifeless bodies are consumed by the ocean. As to the fourth man, the cadet soldier Andries Liebent, he now tearfully pleads for his life, begging between sobs that they spare him. Zevanck considers it. He knows Liebent to be a willing worker and has previously detected a promising strain of cruelty in him. He decides to allow it on one condition. That is, that he joins them as a Mutineer and swears fealty to Jeronimus. Weeping with relief at his salvation, Liebent agrees to do exactly that.

That afternoon, the Mutineers return, and Zevanck reports to all on Batavia’s Graveyard that Wiebbe Hayes and his men are going well, that they are hopeful of soon finding water, that there is a lot of food and that they welcome more people from Batavia’s Graveyard coming over. If some think it is a little strange that Andries Liebent has returned, when he was meant to be one of the ones going to join Hayes, no explanation is considered necessary, and there is general rejoicing not only that Hayes and his men are all right but also that they want more people to join them.

7 July 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

The next lucky three who are announced to be going to the High Islands with David Zevanck and his men are the cadet Hans Radder, the trumpeter Jacop Groenewaldt and the clerical assistant Andries de Vries. Why them? The reason that Jeronimus gives is that they all possess skills that Wiebbe Hayes says are most needed on the High Islands. The real reason, however, is that the young soldier Mattys Beer has told Jeronimus that these three are

‘kakelaars’

, cacklers, men with no loyalty who are quick to complain, and, should the Company send a rescue yacht to these islands, they would be the first to report any irregularity to the VOC.

This time, it goes almost as before.

The three men get onto the raft in the mid-morning with such possessions as they have and wave goodbye to those who farewell them on the shore, waves that continue until the raft disappears around the northern lip of Seals’ Island. And then, once again, the Mutineers suddenly fall upon the three men and they are soon tightly tied, hands and feet. The terrified men are then obliged to lie on the raft, all trussed up, while the Mutineers change course. After just 20 minutes, with one of the assailed now softly weeping, they arrive at another small island, which lies on the other side of Seals’ Island, beyond the sight of Batavia’s Graveyard.

And

there is a job of work to be done

.

As before, there is no need to go through any pretext of legality, of their execution being by order of the council, etc., for whatever imagined crimes. With no preamble, the Mutineers simply get on with it. First, Hans Radder is carried by the Mutineers into the shallows, just beyond the shore, and dropped in, his face to the sky. Radder’s scream is instantly drowned out as his head goes beneath the waves, and from there it is relatively easy. Though there is

a good deal of thrashing and bucking

, it is nothing that a grinning David Zevanck – for it is he who has stepped forward to do the honours – cannot handle with relative ease.

Barely interrupting his conversation about how they will have to bury them once they are dead, to prevent any chance of their bodies washing up on Batavia’s Graveyard, he simply places his foot on the man’s side and prevents him coming to the surface. True, with one furious buck Radder manages to briefly break free and even bring his head above the water for one last massive gulp of air before he goes under again, but this only peeves Zevanck. He quickly regains control and this time presses down harder with his foot,

grinding

the man down. And, sure enough, within a minute, the struggling has ceased. There is merely one last huge and momentarily foul-smelling bubble that comes to the surface . . . and that is it.

Zevanck takes his foot off, and then he signals for the other Mutineers to bring from the shore the weeping Jacop Groenewaldt, who is now pleading for his life. By the time the Mutineers have gripped the second man, the first has floated to the surface, his face purple and bloated. He is dead. With one look at him, all the fight goes out of the second man, and this time the whole drowning takes less than a couple of minutes.

And now it is Andries’s turn.

‘Nee! Nee! Nee!’

Andries de Vries screams. ‘Please! Please spare me! I will do anything!

Anything!’

Zevanck holds up his hand, and the Mutineers pause for a moment.

Anything?

This could be very amusing, and an interesting experiment. On the spot, Zevanck has an idea and decides to spare Andries’s life, at least for now. After all, though Andries possesses no valuable skills, he is a weak man and will never present a threat to them. The sole downside of his continued existence is that his is another mouth to feed, which, though significant, can be counteracted if he eliminates more mouths. So he is taken back to Batavia’s Graveyard and, after Zevanck consults with Jeronimus, Andries is told that he will shortly have a meeting with Jeronimus, where they can discuss an important matter.

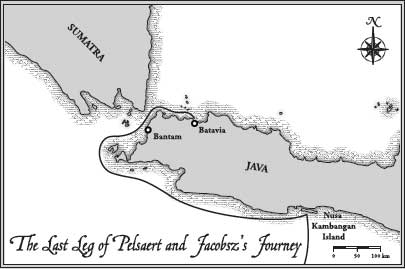

7 July 1629, Batavia

On the tail of this shining day, Commandeur Francisco Pelsaert, aboard the

Frederick Hendrick

, first sights Batavia in the distance before arriving there just an hour later. As the anchor is dropped, the rays of the setting sun illuminate the foreboding dark-blue coral stone of the citadel, the heart of Dutch power in the East Indies, which dominates both the harbour and the surrounding countryside. For Pelsaert, and most who have survived the long ordeal, it really is a matter of thanking God the Lord for His supreme mercy in having delivered them all from the very jaws of hell, to here, their long-awaited destination.

True, gazing shorewards, it is not remotely as Pelsaert remembers it from several years earlier, as the attacks of the soldiers of the Sultan of Mataram have left whole sections of the old settlement in complete ruins. But compared with the barren wilds of where he has come from it still looks to be the very height of civilisation. And yet, despite having finally arrived, Pelsaert decides to remain aboard and go ashore on the morrow. For the moment, he simply wants to savour the fact that their physical ordeal is over, before facing the new ordeal of explaining how it all occurred.

Notwithstanding the fact that Pelsaert’s own safety is now assured – at least in the short term – he cannot help but wonder, as he sips wine in the

Frederick Hendrick

’s Great Cabin, gazing into the twinkling lanterns of Batavia, just how those back on the Abrolhos Islands are faring . . .

8 July 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

On this wild morning, down by the beach, a sad little group of survivors is gathered around the

Predikant

as he holds his daily service. It includes, of course, all the members of his own family plus something of a graveyard gathering of those who still have the energy and will to attend his service, who still steadfastly believe, despite everything, that the Lord is with them even now.

‘My brethren,’ he pronounces, his voice rising to get above the now whistling wind, ‘I tell you all that Almighty God and all of His holy angels will come and take us all under their wings and . . .’

And suddenly the

Predikant

is aware of some chortling going on behind him, even as he sees a stunned expression on the faces of the gathering as they look over his shoulder. He turns to see several of the

Kapitein-Generaal’s

red-coated men, led by an insanely grinning Mattys Beer and Lenart Michielsz van Os, cavorting around and waving the bloody, severed flippers of sea lions above their heads as if they are the angel wings he is referring to.

‘There is no need,’ Beer sneers at him in a manner that he clearly thinks is hilarious, ‘for we already have the wings!’

The Mutineers fall about with laughter

, as if this is the greatest joke ever told, but they are also serious: no longer will they have the

Predikant

talking of God, angels’ wings and such things.

The service instantly breaks up.

Within minutes, the outraged

Predikant

is before the

Kapitein-Generaal

, making a formal complaint at this outrageous behaviour. Yet, to his complete amazement, Jeronimus gives him short shrift. Not only does he refuse to punish his men, he also tells the

Predikant

that just this morning the

raad

has decided on a new edict: there are to be no more services of worship held, and not even any praying. The council has decided that such things are a luxury that can no longer be afforded, as all energies must be focused on ensuring their survival, not asking for God to ensure it. Never in his life has the

Predikant

been so appalled, and yet, again, it requires more strength (and less sense) than he has to protest

too

vociferously.

Jeronimus watches him go, amused at seeing the struggle in the

Predikant’s

soul between his outrage and his fear, with fear winning out in the end – as he was certain it would. The

Predikant

will not be a problem after all, which may well assure his survival. The main thing is that the

Predikant’s

services have now been entirely shut down. For things have to change.

Jeronimus is now fully intent on establishing, if not heaven on earth, then certainly his own kind of hell. Back in the day, Torrentius could only dream of having the opportunity he has now, of establishing an entire society without the fetters of God placing restrictions on behaviour. Already, he has encouraged blaspheming among the Mutineers as a way of liberating them and has talked extensively of his ideas that there is nothing they can do that God hasn’t first put in their hearts; the banning of all religious manifestations is the next step in the transformation. No longer will he have the

Predikant

talking of God, when it runs directly contrary to what he is endeavouring to create. On this island, at this time, the

Kapitein-Generaal

is determined that there is to be no God but ‘I, Jeronimus’.

Yes, Jeronimus is now a modern-day Caesar – his every word is law, and, if he chooses,

de dood

, death. Never in his life has he known power remotely like it, and he finds he adores every moment of it. But, render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s – does he not need, at the very least, a comely concubine?

He does. And there can be only one choice. If Lucretia Jans, wife of Boudewijn van der Mijlen, thinks her own nightmare cannot get any worse, she is sadly mistaken. On this day, she is led to the

Kapitein-Generaal’s

tent by Coenraat van Huyssen and advised that, by order of Jeronimus, this is where she will be residing from this point.