Bad Lawyer (39 page)

Authors: Stephen Solomita

When Omar eventually cops to Rob 1 and is shipped off to Sing Sing, I find someone to replace him. When I, in turn, plead to Murder 2, and am transferred, first to Clinton, then to Attica, then to Green Haven, my reputation precedes me and I find cons with serious clout eager to become my partner. Even so, my incarceration is not without its negative moments. I have been attacked many times, and on one occasion beaten into unconsciousness.

A month after I enter the Clinton Correctional Facility I’m called to the office of Warden Thelonius Teagarden. Before he can threaten me, I vow that under no circumstances will I participate, now or ever, in a legal challenge to his or any other institution, that I am purely and simply a businessman. For this reason, and because I have done legal favors for dozens of corrections officers, I have never had my work confiscated, never been denied use of the law library or prison post office. It is also the reason, I am convinced, why I still possess the photographs gathered from my office three weeks after Priscilla’s death by a newly impoverished Pat Hogan.

I keep the photos, of Caleb’s and Magda’s respective families, of Caleb, Julie, and myself, in a small wooden box made for me by a client in the Attica woodworking shop. The box is held together with dovetailed joints instead of nails or screws, thus allaying the fears of always nervous C.O.’s. The photos, of course, are far too precious to be displayed on a wall. No, like any other family treasure, they must be hidden away, protected from enemies and the elements, perused in secret like the fuck books that ignite the fantasies of my incarcerated brothers.

Priscilla died without making a sound. Her life’s blood, mixed with pea-sized chunks of brain and shards of skull that had the feel of broken teeth, fell over Thelma Barrow and myself like an unexpected summer rain. Though I felt as if I might drown in blood, I was distinctly attracted to the heat and the wet, to the viscous feel of Priscilla’s blood on my face, in my hair.

The atmosphere in the little courtroom was instantly saturated with the screams of innocent bystanders. I was yanked backward, slammed to the floor, rolled onto my face, and handcuffed. Still, they continued to scream and their screams blended in my ear like voices in a choir. As I was literally dragged from the courtroom to the pens, the blood flowing from my broken nose mixed with Priscilla’s to fall sweetly on my tongue.

I think of Priscilla far less than I would have predicted, and of Magda far more. I’ve already said that I watched my mother twist in the wind. What I have not said, what I’ve only remembered since coming to prison, is that after Gregor’s appearance (and before the nature of his scam grew too apparent to ignore) I became my mother’s confidant, that we became closer than we’d ever been, closer than we’d ever be again. Not only did Magda read Gregor’s letters aloud to me over lunch, but she spun little thumbnail sketches of this or that aunt or uncle or cousin, often keying her tales to whomever Gregor Glitzky was pursuing. These stories, as I remember them, had an impish quality, formed as they were in the mind of the child who’d left Budapest years before.

Of course, I was blind to the gravity of Magda’s search, how much of her very life was at stake. All I knew was that my mother was happy and that she’d included me in her happiness as she’d never included me in her pain. When she pulled away from me, I became …

That’s as far as I’ve gotten and as far I want to get: a little boy huddled over a bowl of potato soup, inhaling the blended fragrance of leeks, parsley, and dill, listening to his mother’s voice, to the twin emotions of hope and happiness, accepting them as love.

About Priscilla Sweet’s last moments, as has already been stated, I remember only bits and pieces. Still, I’m certain that I carried my .32 into Judge Delaney’s courtroom that day as I’d carried it many times into many courtrooms. Like any other red-blooded American male, I loved the feel of a lethal weapon, the danger of it, the illusion of physical security generated by its mere presence. I’m also certain that if I’d been unarmed that afternoon, Priscilla would still be alive, that I lacked the courage to formulate the necessary intent to commit murder. Nevertheless, I was indicted for murder.

Though even Mary Immaculata Corvelli, the ADA assigned to prosecute me, agreed that my crime lacked the aggravating factors necessary for a sentence of death, I faced upon conviction two very ugly realities: life without parole or life with the possibility of parole after twenty-five years. Ever the positive and practical attorney, over the next two months I kept reminding myself that I would rejoin the free world at age 72, assuming I received the latter sentence and with time off for good behavior.

“Americans are living longer than ever,” I explained to Omar Skepps over a game of chess. “Healthier, too.” Around us, seventy-five merciless criminals howled, shouted, cursed, played a dozen radios tuned to a dozen stations. “What I have to do is plead it out.”

“Why the man gonna give you a plea?” Institutional almost from birth, Omar had developed a practical side of his own. “Bein’ as you got nothin’ to give back.”

“Because,” I told him, “if they don’t, I’m gonna plead not guilty by reason of mental defect and represent myself.”

I’ll be eligible for parole in a mere sixteen years.

Phoebe Morris will arrive to collect these last pages in a few hours and I have still not begun to approach the central issue. Phoebe has done extremely well over the last few years, jumping to the

New York Times,

then establishing a syndicated column that runs weekly in a hundred newspapers.

We’ve cut a deal, Phoebe and I. For a fee and the right to put her name on the cover and add chapters of her own, she will market the manuscript, see to collecting advances and royalties. In New York, according to a law that has already been once declared unconstitutional and rewritten, convicted felons are not allowed to profit from their crimes. We shall see.

About the killing of Priscilla Sweet let me say the following. On the one hand, I did not feel obligated to avenge Caleb and Julie. Not only had I not sent them to their deaths, I had insisted they remain home on the night in question. In so doing I had exercised, as they say in the legal biz, due diligence.

On the other hand, I must certainly have felt, on a level below pure (and mere) obligation, compelled to exact some measure of revenge. Why else would I have formulated so many truncated plans for revenge? True, I constructed a number of elaborate rationales in support of Priscilla’s innocence before Hogan presented me with the proof positive. But I can argue that my rationales smacked of desperation precisely because I knew that something had to be done and I didn’t want to do it. Viewed through that admittedly dark lens, Priscilla Sweet, when she stood up to her loss, when she bargained for her share of the blood money, when she refused to acknowledge the pain of any lesser punishment, invited her own death.

I was in residence at the very scenic Clinton Correctional Facility in northeastern New York State, maybe nine months into my sentence, teaching remedial English to a class of hardened cons who stood no chance of demonstrating their skills anytime in the near, or even distant, future, when a half dozen corrections officers barged into the room. The squad was led by a middle-aged, paunchy lieutenant named Harrelson who ordered us to undress for a search. There was nothing personal in this, certainly not on Harrelson’s part. A CO had been stabbed in the mess hall a few hours before and the population was now paying the price.

Ever the good inmate, I stripped down without complaint, then lined up against the chalkboard to await developments. One by one, the other cons joined me, but it wasn’t until the last man approached that I was jolted from my carefully cultivated air of indifference. Johnny Caitlin, the con in question, had two scars—two circular raised scars, each about the diameter of a cigarette—side by side in the center of his chest.

Later that night, I described the scars to my cell mate, a professional criminal who’d accumulated several decades of hard time, and asked him what they signified.

“You don’t know?” Aureliano Aguirre loved to display incredulity in the face of my inexperience. “You never seen that before? Where you been all your life?”

I was tempted to reply that, unlike himself, I’d spent the major part of my years on the planet a free man, but settled for repeating the question.

Aureliano laid back on his bunk and shook his head. “You see scars like that,” he told me, “you stay away. Them scars are the mark of a snitch.”

As they say on the Rican side of the dining hall:

Chinga tu madre, maricon

.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

copyright © 2001 by David Cray

cover design by Erin Fitzsimmons

978-1-4532-9062-0

This 2013 edition distributed by MysteriousPress.com/Open Road Integrated Media

180 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

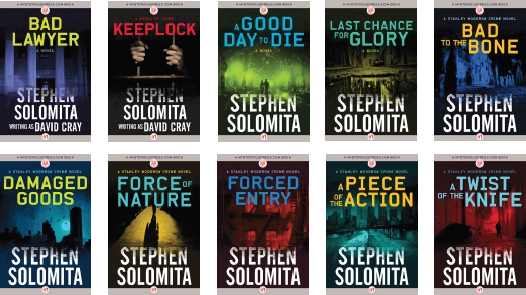

STEPHEN SOLOMITA

FROM MYSTERIOUSPRESS.COM

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA

Available wherever ebooks are sold