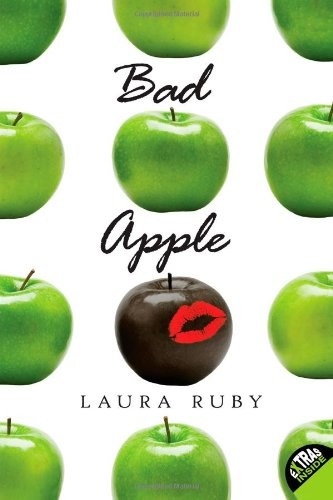

Bad Apple

Authors: Laura Ruby

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Social Issues, #Adolescence, #Girls & Women

Laura Ruby

For Ray of Sunshine

Shine on

The way to read a fairy tale is to throw yourself in.

—

W. H. Auden

All children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.

—

Pablo Picasso

Mr. Mymer, my art teacher, is tall and skinny with floppy hair the color of yams and a peculiar affection for “funny” T-shirts:

CLUB SANDWICHES, NOT SEALS. YOGA IS FOR POSERS. FULL FRONTAL NERDITY

. When my mother met him at parent-teacher conferences, she said he seemed like a very interesting person. She doesn’t say that anymore. Now she says things like he’s “evil,” “a criminal,” and “a predator.”

After she says these things, she sometimes stares at me as if I’m a wounded bird flapping around her living room—maybe something you want to help, maybe something you want to smack with a broom. She opens and closes her mouth as if she might call

me

a name, too, but she never does.

I think the name is “liar.”

My father didn’t go to the parent-teacher conferences. He was on his honeymoon. His new wife is Hannalore, which is

German for

I keep poisoned apples in my purse

.

“No, stupid,” says my sister, Tiffany. “It’s German for

I haul spoiled stepchildren into the woods and leave them for the wolves. I gather the bones that are left and crush them to a powder. I drink the powder in my afternoon tea. It keeps my skin looking young.”

Hannalore is six hundred feet tall and looks like one of those opera singers. You know the ones. They wear the metal breastplates and the big hats with the horns. They’re always the last to sing.

Like Hannalore, the Brothers Grimm also came from Germany. We all know what kind of tales the brothers had to tell. Bad things have gone down in Germany.

“You’re such an idiot, Tola,” says my sister, her eyes narrow as punctures. “Ever hear of the Spanish Inquisition? The Salem witch trials?

Slavery?

Bad stuff goes down everywhere.”

But my sister doesn’t really care about the Brothers Grimm or anything else. After a few minutes of talking about it, she suddenly shrieks: “Shut up! Shut up about the Brothers Grimm! Why does everything you say have some sort of literary reference? Why do you carry around that stupid book? How pretentious are you?”

Someone who wears lavender contact lenses shouldn’t talk about being pretentious. I refuse to call my sister Tiffany, so I call her Madge. Madge is eighteen going on Crypt Keeper and cries all the time. I often find her curled up on her bed, wailing like a lost kitten. When you ask her what’s wrong,

she can never explain. “Life,” she says. Or, more specifically, “Everything.” Sometimes she hyperventilates. She carries around a supply of brown lunch bags just in case she has to sit and breathe into one.

Only people named Madge breathe into brown lunch bags.

Madge has been to four doctors—one regular one and three therapists. She doesn’t like therapists. She calls them voodoo headshrinker freaks. She says that all they want to do is blame our parents for her problems when it’s the whole world that’s in pain.

I myself have not been to any therapists, which is funny, considering that my sister is (was?) the golden girl and I’m the bad seed. Five years ago, at one of the parent-teacher conferences my mother enjoys so much, my sixth-grade math teacher told my mother that though I was doing better in class, I still stared out the window and appeared stupid. Those were her exact words, too. “She still stares out the window and appears stupid.” This is not the sort of thing you say to my mother about one of her children. My mother used her coldest voice—the voice so arctic and furious that icicles spiked the air as she spoke—to tell off my teacher. It took a while. A half hour, maybe. (I’m not sure how long because I was staring out the window and appearing stupid.) My teacher got paler and paler as my mother told her how

inappropriate and ridiculous and irresponsible this comment was and how rude and naive and inept the teacher was. My mother talked until the teacher blended in with the white board behind her. And then my mother grabbed my arm and yanked me from the room.

In the car on the way home, my mother used that same freezemonster voice to tell me that I’d better start paying attention in class and living up to my potential, or she would send me to a monastery in Nepal, where I’d spend my life combing fleas from the yaks.

I told my grandpa Joe what my mom said. He patted my hand and declared that he’d never met a yak he didn’t like.

Me, Mom, Madge, and the yaks. Sounds bad, but it’s not. It wasn’t. Take the teachers. Most of them are nice. Sometimes I draw portraits of them and leave the pictures on their desks. That doesn’t thrill some of the other kids, who think I’m a brownnoser. But that’s not true, either. I like to draw, and the teachers are there just waiting to be drawn. Besides, the things I draw aren’t

always

the kinds of things that teachers find flattering. Like, say, putting Ms. Rothschild’s head on a rabbit’s body. Or drawing Mr. Anderson with a tail. Ms. Rothschild thought her portrait was hilarious; Mr. Anderson, not so much. Actually, that last drawing got me a trip to the principal’s office.

The principal: “Is this supposed to be a joke?”

Me: “No, it’s a present.”

The principal: “A present?”

Me: “As in gift.”

The principal (muttering) : “You couldn’t have given him an apple?”

Me: “You think he would have liked fruit better?”

The principal: “You’re a smart girl, so I’m going to be blunt. I think you’d be a lot happier if you stopped acting so weird.”

Me: “Who says I’m not happy?”

But maybe he was right, because nobody’s happy now.

Before Mr. Mymer, these are the kinds of things that people said about me:

- In third grade, Tola Riley ate nine funnel cakes at the school carnival and then puked them up on the Tilt-A-Whirl.

- In fourth grade, Tola Riley stole Chelsea Patrick’s American Girl doll—one of those creepy twin dolls—and tried to flush it down the toilet, flooding the school bathroom and causing thousands of dollars’ worth of damage.

- In sixth grade, Tola Riley ran down Josh Beck, the fastest kid in the whole school, so she could rip out a lock of his hair to use in a spell.

- In eighth grade, Tola Riley drew a picture of one

of her teachers with a noose around his neck and was almost suspended. - In ninth grade, Tola Riley was caught making out with Michael Brandeis in the broom closet and was almost suspended.

- In tenth, Tola Riley was caught making out with June Leon in the girls’ room and was almost suspended.

- In eleventh, Tola Riley was making out with John MacGuire at a party when, for no reason at all, she smashed him in the head with a fishbowl and swallowed the goldfish.

- She has strange piercings in mysterious places.

- She’s descended from fairies, trolls, munchkins, and/or garden gnomes.

- She has ADHD, bipolar disorder, Asperger’s, and/or psychic powers.

I think this stuff is funny; at least, I used to. No one really believed any of the stories; they just needed something to talk about. Everyone loves a villain. Or maybe not a villain, exactly, but someone you can point out and say, “I might be weird, but I’m not weird like

her

.” I was cool with that. I had my friends. I didn’t need to be like the rest of the drooling high-school idiots—obsessed with sex, YouTube, MySpace, Facebook, texting, drinking, and UV rays (

Orange is the new tan!

). Let people think I was crazy; let them think I would say anything, draw anything, do anything—what did I care?

Now that I do care, now that I’m trying to tell my own story, no one is listening. Madge says I haven’t helped my case by chopping off my hair and dyeing it a shiny emerald green (in addition to the nose ring my mother nearly had a stroke over).

I say, “About a hundred other juniors have dyed hair and pierced body parts. And that’s just the guys.”

“Congratulations,” says Madge. “You’re a teenage cliché.” She goes back to applying her makeup, or reapplying what she’s cried off. “Don’t walk too close to me in the mall today, okay? I don’t want anyone to know we’re related.”

“I never made out with Michael Brandeis, you know,” I say. “He made that up.”

Madge shellacs her bloodless lips with gloss. “Who?”

For the record:

- I didn’t throw up.

- I buried it under the monkey bars.

- Hell hath no fury like the boy beaten in the hundred-yard dash.

- It wasn’t a noose; it was a necklace of bones.

- No.

- It wasn’t the bathroom; it was the art room.

- The fish was saved.

- The nose is strange and mysterious enough. Just try to draw one that doesn’t come out looking like something that belongs on a grizzly bear.

- Fairies, definitely.

- I know what you’re thinking right now.

You’re thinking:

Is

she a liar? Or is she really crazy?

All I can tell you is that I read too many fairy tales about children left to be roasted by hags, vengeful stepsisters so desperate for love they’ll cut off their own feet, and girls locked up in towers with only their hair for company.

I didn’t know all the tales were true.

(

comments

)

A Willow Park High School art teacher, Albert Mymer, was suspended with pay pending an investigation into an alleged relationship with a sixteen-year-old student.

According to a witness, the teacher and student were observed lunching together at a New York City café. Sources within the school administration say that the witness, a fellow student of the alleged victim, described inappropriate personal contact. She also described an exchange of gifts, including a book. Other witnesses interviewed suggest that this is a pattern of behavior.

“I would like to say I’m shocked,” said a coworker of Al Mymer, who wished not to be identified. “But I’m not.”

Police and school officials are continuing their investigation.

—

Dana Hudson

, North Jersey Ledger

“Subject was interviewed at her house with mother present. She was cooperative but guarded during interview. Denied allegations of abuse but admitted that she wanted to protect her teacher from punishment.”

—

Detective J. Murray

“She sort of lost it when my—I mean

our

—dad left us, and my mom started treating us like we were in kindergarten. At least, that’s what my therapist thinks. If you can trust the opinion of a therapist. Which, mostly, you can’t. Therapists are crazy.

“Look, she’s always been weird. She was born that way, so it’s not like you can blame her—at least not totally. No one asks to be born.”

—

Tiffany Riley, sister

“It’s true that I was focused on other things at the time. I admit that. I take full responsibility. Maybe if I’d been around a bit more, none of this would have happened.”

—

Richard Riley, father

“Do you really think that it was just that one time? Give me a break. That skanky little freak is getting exactly what she deserves. Sooner or later, everybody does.”

—

Chelsea Patrick, classmate

It’s been two weeks since the rumors started, one week since Mr. Mymer was suspended, and four days since my mom had to change our phone numbers. I’m still allowed out of the house, but—ironically—only for school. No clubs. No activities. Except for homework, no computer. And no talking to the reporters who skulk around the house or just outside school grounds. My mother is protecting me until the school-board meeting, where she will attempt to get Mr. Mymer suspended permanently and publicly. Where she will throw me to the wolves.

Mr. Doctor, my mother’s husband, drives me back and forth to school. This is okay with me because it is November and damp and cold. Mr. Doctor keeps the radio off, preferring to hum as he drives. He thumps his palms on the steering wheel to the EZ listening music that loops in his head. Despite the cold outside, the windows are cracked.

Mr. Doctor is fond of the word

brisk

. Mr. Doctor should move to Siberia, where brisk is a way of life.

“Can we close the windows?” I say.

“Hmmm?”

“The windows? I’m cold.”

“Oh,” he says. He presses a button. No windows close, but hot wind shoots from the vents in front of me. My eyeballs start to dry out, then water. Mr. Doctor sees me wiping at my eyes and manages to look both irritated and terrified.

“Don’t worry,” I say. “I’m not crying.”

“Oh. Well.” He clears his throat. It is hard for Mr. Doctor to hold conversations like a normal person. “I suppose I wouldn’t blame you if you were.”

“Nothing happened. I keep telling everyone.”

He doesn’t say, “Witnesses.” He doesn’t say, “Investigation.” He doesn’t say, “Pants on fire.”

He says, “Um hmm,” in a way that neither agrees nor disagrees. He’s Neutral with a capital

N

, that Mr. Doctor. He’s our personal Switzerland.

“Why doesn’t Mom drive me to school?”

This he doesn’t even try to answer. We both know it’s a stupid question. Mom makes him drive me and Madge everywhere. (You’d think that Madge would want to drive herself around, but Mom’s afraid Madge will have a crippling panic attack and end up in a ditch.) I think that’s why Mom married him: his willingness to jump in the car at every opportunity, like a Labrador with a license.

But then that’s not the only reason why Mom picked him. There’s the money. The security. The teeth. Mr. Doctor is an orthodontist. Half my middle school went to him.

I

went to him. That’s where he and my mom met. Both of them lingering in the examination room, discussing the Lost Art of Flossing.

“Most people would have taken me out of school,” I say. “Most

mothers

would have.”

Mr. Doctor keeps his eyes on the road. “Do you want to be kept home?”

At first, my mom wanted me to scream and cry and make a grand confession. She wanted me to go to therapy. She wanted me to name names so that she had someone to punish. But I wouldn’t. I won’t.

“No, I don’t want to be at home.”

“That’s what I figured,” he says. “Besides, your mother is not most mothers, is she?”

He rolls to a stop in front of the school and pops the lock. He waits until I get inside the building before driving away.

I walk down the hall, feeling the weight of eyes. I’ve always felt the weight of eyes, but now they’re heavier, like I’m wearing a lead dress.

I steer past the trophy case, where dusty trophies trumpet the kind of athletic achievements the school hasn’t had in years. A clot of freshmen—you can always spot the freshmen—gape. Faster now, I walk by the main office.

Inside, the secretary glances up and frowns at me. The halls around the office have been freshly painted, a long expanse of white just begging for decoration. What would I hang there?

Who

would I hang there?

Even though I’m on the lookout for enemies, I haven’t walked far when someone accosts me, one of the Whitestone twins; I can’t tell which one. Her gray eyes glint like rocks at the bottom of a stream as she says, “So. Is he going to leave his wife? Are you guys gonna run off to Mexico or something?”

I say, “Nobody’s running anywhere.”

“Did he promise to marry you?”

“He didn’t do anything.”

“That’s not what I heard,” she says.

I hate people; that’s my problem. “The truth is,” I say, “he’s having my baby. It’s a medical miracle. Someone call the newspapers.”

“Nice

hair

,” she spits. She stomps off, her cheerleader skirt swishing.

I’m not the only one who loves Mr. Mymer.

I make it to my first class without anyone grabbing my backpack and throwing it in a toilet. Madge says I should just drop out since most of my classes are a joke. Which is true. Except for art, I don’t take honors classes, I don’t take AP. I’ve always preferred slogging along with the druggies, the

perpetually confused, the motivationally impaired. Maybe not a great plan for a girl in my situation. Mr. Lambright, my lit teacher, makes desperate attempts to interest us in words, in meanings. He plays scratchy old records on an ancient record player and has us study the lyrics.

“

Before our eyes, buzzing like flies

. Now, what do you think that means? Anybody? Loren? Jamie? Miles? Miles!”

Miles isn’t interested in song lyrics. Miles has spent the entire period pointing at me, performing obscene tongue acrobatics for the entertainment of his friends.

“Miles Rosentople!”

Miles slurps his lizard tongue back in his mouth. “Huh?”

“Is that good or bad?”

“Is what good or bad?”

“The phrase ‘buzzing like flies.’ Do you think that’s a good or a bad thing?”

“I don’t know,” he says. He licks his lips, still smirking at me. “Good?”

In my next class, Mr. Anderson prepares us, his little biology soldiers, for the arrival of fetal pigs, which we are to dismember for credit. I don’t know why we can’t get a formaldehyde-free computer program and

pretend

to dissect the pigs. Maybe because Mr. Anderson is almost a million years old, joined the marines when he was six, and believes that we’re all part of the food chain and always had and always would eat or destroy one another. “Look,” Mr. Anderson says,

“if you were one of the last humans alive and you were stranded in the Kalahari Desert, do you think that a lion wouldn’t eat you if it were hungry? Do you honestly think that one lion would say to another lion, ‘Hey, don’t eat the naked, defenseless two-leggers, there’s only one thousand three hundred and sixty-three left in the world’? Baloney! And that’s exactly what these pigs would be if we weren’t using them to get you kids interested enough to learn a little science—baloney! And that’s life, my friends! Better accept that now!”

As he rants, I slip the copy of

Grimm’s Fairy Tales

from my backpack and flip through the pages, reading the notes that my father scribbled in the margins back when he was a frustrated teenager forced to flay unsuspecting frogs:

Good and evil aren’t abstract concepts. Always use your magic for good. This class is bogus

.

In history, we have a mock election. When the results are tallied, it turns out that a bunch of us voted for someone we could never in a million years picture as the leader of the free world. We eye each other with suspicion, wondering who the traitors are.

Then, Cooking II. Mrs. Duckmann, aka the Duck, doesn’t believe in cooking. She believes in splitting recipes in neat columns of fractions. She believes in measuring accurately using the right instruments—dry ingredients in little beige plastic cups, liquids in the clear glass. But today she’s

changing things up. Today, says the Duck, we are going to apply what we have learned in our unit “The Egg” to make something basic but essential for many recipes.

“Today,” she announces, with all the fanfare of a newscaster announcing the results of the Super Bowl, “we are making mayonnaise.”

My partner, a ginormous senior who looks like a Transformer—I imagine his parts swiveling and recombining to change him from a human to an industrial fridge—breaks out in applause.

I raise my hand. “Couldn’t we make something more complicated? Like cookies, maybe? Cookies have eggs.”

Some of the teachers won’t look at me; some of the teachers won’t stop staring. The Duck’s eyes widen as if surprised to see me sitting in front of her. Her numerous wrinkles fold in origami patterns of concern. She looks like the witch in “Hansel and Gretel” must have looked right before she threw Gretel in the oven.

“If the lesson is upsetting you,” she says sweetly, “perhaps you’d like to go to the principal’s office?”

The principal is not happy to see me.

Art, finally. Mr. Mymer is gone, but the art room, his room, is still my favorite place to be. I love the smell of paint, of clay and charcoal, the smells of things that make you believe that you will be okay.

I remember walking into the art room as a freshman and gaping at the giant murals on the walls, paintings on easels, sculptures made of wire and Styrofoam.

It was the only class I was looking forward to, even then. My dad was an artist, a sculptor. He made architectural models. Little houses, buildings, office parks, all perfectly scaled down to size. For my sister and me, he made Cinderella’s castle, the humble cabin of the Dwarves, Rapunzel’s tower. Who needed dolls?

So, that first day of high school, I brought a tiny house I’d built. A crazy off-kilter house, the kind of house some kind of punk fairy would have built for herself. But I didn’t know it would be so hard to get the details right. My dad helped me cut the wood and the foam boards. I used clay for the rest. I had tucked it carefully in a brown paper bag so that no one would see it until the Big Unveiling.

Mr. Mymer, the teacher, was not old, not young, and built like one of Van Gogh’s sunflowers: big head bobbing on a long, thin stalk. He had a fat nose and a weird black mole begging for surgery on his cheek. He wore black glasses, faded jeans, and some sort of fifties bowling shirt over a T-shirt. The T-shirt said

SQUIRRELS CAN’T BE TRUSTED

. His eyes were huge and bright and bored right into you.

I decided he was hot.

When the bell rang, he was quiet for so long we thought he was having one of those seizures, you know, the ones where people’s brains freeze up, but they look okay from the

outside. Then he said, “I’m supposed to begin by saying art will free you, that it will transform you, that you will find yourself remade, renewed, reborn, et cetera, et cetera. And maybe that will happen for a few of you. But a lot of you will be bored. And all of you are going to be frustrated. Really frustrated. You’re going to want to tear up your drawings, trash your sculptures, slash your paintings. I hope you don’t. Because art will reveal your real feelings about the world better than almost anything else. And who doesn’t want to know their own real feelings about the world? Who doesn’t want to know him or herself?”

He kept talking about what we’d learn and how we’d learn it. That he would consider us adults and that we didn’t have to ask to use the bathroom or go get a drink of water (but he also said not to blame him if some random teacher or administrator caught us in the hall without a pass). That we would work harder than we’ve ever worked in any class. That we should expect to lose a lot of sleep.

I touched the brown paper bag that hid the fairy house. I already knew myself. And I’d had insomnia since kindergarten. I waited impatiently for him to stop talking. I stared out the window. I glanced at the clock.

Finally, the bell.

The other kids filed out of the classroom. I brought the bag up to his desk.

“I have something to show you,” I said. Up close, his eyes were blue enough to hurt.

“And your name is?”

“Tola Riley.”

“Okay, Tola. Let’s see what you got.”

I slipped the fairy house out of the bag and held it out to him like a birthday cake.

My new teacher took the house and examined it from every side. Then he said, “Well.”

“It’s a house,” I said helpfully.

“Yeah, I see that.” He peered inside one of the slanted windows. “Any people in here?”

“Who needs people?”

He shrugged. “Right. So, what moved you to build a house?”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, why a house? Why not a dog? Or a train? Or a train made of dogs?”

I had no idea what he was talking about. I said, “Huh?”

“What were you trying to say with this house?”

Was he being deliberately stupid? “I was just trying to make a cool house.”

“Hmmm,” he said, nodding. “Okay.”

This was not the reaction I’d been going for. “So you don’t think artists should build houses. Houses are not worthy.”

“Oh no, no! I think it’s fine to build houses. There’s an old saying about art: ‘Practice what you know, and it will help to make clear what you don’t know.’”

I frowned so hard my eyebrows ached. “Who said that?”

“I don’t know who said it. Rembrandt? Picasso? I can never remember. But it’s true. The more you build these little houses, the more you’ll realize how much you don’t know about little houses. Maybe you don’t even like little houses.”

“I

love

little houses,” I said, taking my own little house and shoving it back in the bag. I wanted to smash it to the ground.

At lunch, I called my dad. “My art teacher is a butthead.”

But no, no, he wasn’t. And I discovered that I didn’t like little houses so much unless my dad made them for me. I started painting instead. I learned that I could fall into a painting and not come out for days. That painting took me to places I never imagined going, like a train made of dogs.