B004R9Q09U EBOK (16 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

The work had originated in the early Greek Christian community, persisting through the ages as successive generations of monks copied the manuscript and passed it around from monastery to monastery throughout early Christendom. Its origins stretch far back into classical antiquity. The textual material evolved from a seminal Greek work known as the

Physiologus

(meaning, “The Naturalist”), whose bibliographical lineage stretches through a number of other books dating back to the reign of King Solomon. Parts of the book can be traced back to Pliny and Aristotle, some even further back to stories of Indian, Egyptian, and Jewish origin. In other words, the

Bestiary

contained a healthy dose of folk wisdom from ancient oral tradition. By echoing the themes of popular folk taxonomies and portraying animals as symbols of other divine truths, the

Bestiary

may have

struck a deep unconscious chord with its illiterate audience, who may have felt the stirrings of an ancient wisdom tradition at work.

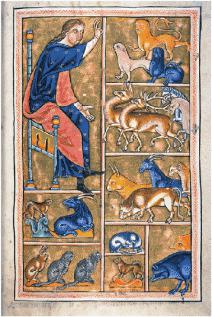

Adam naming the animals, from the

Aberdeen Bestiary

, Folio 5r. Copyright by University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, England.

The book was full of allegorical stories, using the figures of animals to tell a larger story about Christian theology to people who lived, for the most part, in an oral culture. We have seen how folk taxonomies give rise to synaesthetic knowledge systems that persist with remarkable fidelity in oral cultures. In the oral culture of the late Dark Ages and early medieval era, the

Bestiary

tapped into this vein of folk wisdom while at the same time serving as a kind of boundary object between oral and literate cultures, introducing illiterate audiences to tales that were undoubtedly meant to be heard aloud yet were nonetheless obviously encased between the covers of a codex book.

The

Bestiary

almost always begins with the image of Adam naming the animals, making a biblical claim for humanity’s divine right to name—and, by extension, categorize—the beasts of the earth. “To name is to control,” as Whit Andrews puts it, “and to establish primacy and the right of exploitation.”

1

In this image, Adam not only names the beasts but also appears to assign a rudimentary taxonomy, allotting each beast to a particular box in his scheme. Each animal’s name includes a divine etymology, with families of animals arranged by both family and relative proximity to humankind, with animals “not in man’s charge” (the great cats and other wild quadripeds), followed by animals “for use by men” (like horses, cows, and sheep), and finally “beasts” (like dogs, cats, and boar). This image also echoes the folk classifications of preliterate societies in which affiliate classes provide a category for grouping animals by their relationship to human beings as well as by their relationships to each other.

The author (sometimes also known as “Physiologus”) attempts to draw instructive moral lessons from the behaviors and qualities attributed to various real and mythical animals. Each chapter conforms to a simple pattern: First, an animal is described in physiological detail; then its properties are shown to illustrate a particular theological point, often buttressed with biblical passages. Elephants were said to have no knees; when they slept, they had to lean against a tree, and the tree in turn symbolized “tree of life,” or the pillar of

faith. Lions were said to give birth to stillborn cubs, which came to life only on the third day after their birth, symbolizing the Resurrection. And so on. The

Physiologus

made no pretense at scientific accuracy; these were allegorical tales, meant to illustrate symbolic rather than literal truths.

The

Physiologus

traveled through successive generations of copyists from ancient Greece to libraries as far away as Ethiopia, Armenia, Syria, and Rome. It was in its last translation to Latin that the text took on a relatively stable form that would shape the template for a thousand-year run in successive copyists’ hands across the monasteries of Europe, eventually finding its way into Italian, French, German, Spanish, and English. During this period of northward migration, the work passed through the hands of generations of monastic scribes, evolving along the way to incorporate local nuggets of animal lore and superstition. With each successive copying, both text and image would change slightly as scribes made alterations from the original. One copy served as the basis for the next, and hundreds of small alterations eventually accumulated into significant changes. By the eleventh century, the work contained descriptions of almost double the number of beasts found in the original

Physiologus

, evolving over time through a long process of mutation. Eventually, these iterations turned the work into a whole new book, no longer called the

Physiologus

but instead the

Bestiarum

(“Animal Book”). By the time the genre reached its English heyday, it began to expand toward a proto-scientific form, including entries that found their way into the work with no apparent religious significance. Isidore of Seville’s famous

Etymologies

, for example, contained descriptive materials similar to those found in the

Physiologus

but without the Christian allegories. In these larger works, doctrine and religious interpretation had to share the stage with a more secular and straightforward view of the natural world. Thus, the

Bestiary

began paving the way for the more formal classification systems that would come later at the hands of naturalists like Linnaeus and Buffon (see

Chapter 9

).

Popular demand for copies of the

Bestiary

fueled the development of inventive new reproduction techniques in the monastic scriptoria, methods that in turn allowed the work to reach even wider

audiences. English bestiaries of the thirteenth century bore remarkable similarities to one another. The text and illustrations mirrored each other so closely, in fact, that book historians have surmised that they must have been produced from common master copies. The practice of using such “model books” for the production of popular manuscripts flourished in European scriptoria of this period. In the well-known K manuscript, illustrations reveal small puncture marks tracing the periphery of each figure, along with one hole in the middle of the page—some pricked so forcefully that they penetrate through to the following pages. Samuel A. Ives and Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt have tried to trace some of these techniques through a careful examination of the physical evidence:

The central hole in the miniatures probably served to keep the leaves in exactly the same position during the puncturing process. After they were pricked, the loose sheets were laid onto the pages of the new copies of the Bestiary that were being produced at the workshop. Powder was dusted through them, the dots [were] joined, forming a fine outline drawing perhaps in light pen or thin brush stroke. This was then painted in by illuminator, using the originals as color guides.

2

This process of replication, known as the “punch-transfer” technique, marked an important breakthrough in the technology of book production. Now, scriptoria could produce copies of the same work with much greater speed and accuracy. Although the technique was a far cry from the automated processes of Gutenberg, it marked a major leap forward in medieval information technology. Most of the surviving bestiaries from this period have a hurried, inelegant quality to them—further evidence of mass production. While a few finely wrought specimens survive, the majority bear the mark of hurried production, with spare illustrations and sometimes sloppy handwriting. Most of the surviving bestiary manuscripts of this period feature only a single illustration per passage, while earlier versions contained many more.

In the age just before Gutenberg, the technologies that facilitated the distribution of bestiaries placed the book in a central role in both technological and cultural change. Bestiaries became an important

forerunner of later popular books, in both form and content. The images they contained became a cornerstone of popular Christian iconography for centuries to come, cropping up regularly in the church architecture of the day as sculptural adornments in even the simplest of parishes, where illiterate parishioners would listen to sermons and Gospels and then find those lessons reinforced in the visible symbols of the church architecture. Bestiaries also figured prominently in the medieval school curriculum, taking a place as one of the standard instructional texts along with Cato, Aesop, and Prosperus. This entrenchment in the popular nonliterate psyche explains the hold these images would later have on successive English generations. The images so imprinted themselves on the popular consciousness that they eventually appeared in tapestries, paintings, mosaics, and even fabric cloth. English authors from Spenser to Shakespeare to C. S. Lewis regularly drew on animal imagery that can be traced directly back to the

Bestiary

.

Long after the

Physiologus

faded from the popular fancy, the images and themes it contained persisted, insinuating themselves into the symbolism of later ages. The

Bestiary

’s legacy extends beyond our lingering fascination with imaginary animals, however. Its success helped fuel a popular demand for books that would plant the seeds of the Gutenberg revolution.

As Europe entered the Middle Ages, the production techniques perfected in the monasteries fueled a rising popular interest in books. Once again, information technology was driving cultural change. While literacy was slowly beginning to spread among the monastic and aristocratic classes during the late medieval period, the vast majority of the population remained illiterate. Folk wisdom still predominated, and oral traditions continued to flourish. But the success of the

Bestiary

suggested a new public role for books and writing as more than just instruments of monastic scholarship, but as vessels of popular wisdom.

Across Europe, literacy was reemerging along the contours of a

familiar historical pattern. Just as writing in the ancient Near East had emerged at first in the mode of “craft literacy,” supporting commercial transactions, so the reemergence of writing in Europe may have had at least as much to do with Mammon as with God. As historian Brian Stock writes, medieval Europe’s reencounter with literacy “would seem to have repeated with minor variations a process that unfolded in the eastern Mediterranean centuries before.” Just as in Mesopotamia, “the rebirth of medieval literacy coincided with the remonetization of markets and exchange.”

3

Charlemagne had contributed to the secularization of writing by forbidding priests from conducting business transactions, such as drawing up contracts between illiterate parishioners. With priests barred from creating documents, a new class of secular scribes began to emerge. Coupled with a revival of Roman law in Italy that began to spread across the continent, the newly privatized class of scribblers found a growing market in writing up quotidian documents, including various bonds, pacts, and legal agreements. The privatization of secular writing also yielded an economic incentive for the scribes to market their services. Whereas in the Dark Ages Europeans had largely done business on a word and a handshake, by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries they increasingly could avail themselves of willing scribes who, for a fee, would write down the details of their business arrangements.

Throughout the Dark Ages most people conducted transactions requiring close personal bonds of trust, like the highly ritualized pledges of fealty between vassals and lords (often sealed with a kiss on the lips). Now these old forms of intimate, person-to-person social contracts started giving way to more detached forms of written agreement. Although the vast majority of the population remained illiterate, the technology of writing exerted a growing influence over people’s lives. “When written models for conducting human affairs make their appearance, a new sort of relationship is set up between the guidelines and realities of behavior,” writes Stock. Such documents introduce consensual rule sets that constrain social actions. “Moreover, one need not be literate oneself in order to be affected by such rules. A written code can be set up and interpreted on behalf of

unlettered members of society, the text acting as a medium for social integration or alienation.”

4

In other words, literate civilization is not necessarily predicated on mass literacy.

As written laws and contracts began to proliferate throughout Western Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the function of writing started to change. Documents were no longer just vessels of information—like the word of God, the poems of Virgil, or tales of fanciful beasts. A new class of documents emerged that functioned less as narrative texts and more as facts unto themselves. “Men began to think of facts not as recorded by texts but as embodied in texts, a transition of major importance in the rise of systems of information retrieval and classification.”

5

In a society where most people still could not read, the document served less as a text and more as an externalized “social fact”

6

: its mere existence often mattered more than the particular words it contained. Even today, in an age when most people can read, we still treat many documents this way. For example, how many of us ever read the words in a warranty, a stock prospectus, or a software license agreement? Such legalistic documents typically serve the same function as medieval contracts insofar as they matter more as symbolic seals of trust than as conveyors of textual meaning.