B0038M1ADS EBOK (22 page)

Authors: Charles W. Hoge M.D.

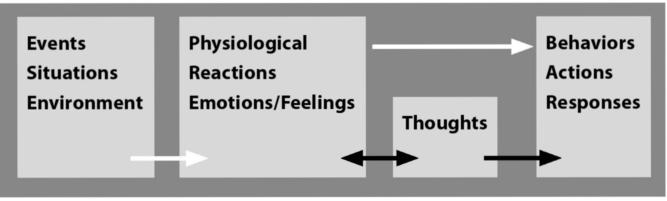

The practice of this skill involves putting space where the dark arrow

is in the figure; i.e., monitor your physical sensations and feelings and

realize you don't have to act on them. It's okay that your body doesn't like

being penned in; that's normal for a warrior. It's okay to be frustrated and

angry at traffic. Accept your feelings, but don't think you have to immediately act on the basis of these feelings. It may be hard, but the skill here is

to accept and tolerate your emotions and develop patience.

Patience is a crucial skill in combat. You may have to wait out the

enemy for days, weeks, or months before you strike, and it's not that different back home. However, many warriors completely forget this skill

when they come home. They can't tolerate the stupid stuff people do, and

instead of remembering to practice this skill (for example, in a supermarket line), they explode at relatively minor things.

Patience can be excruciating, but sometimes you don't have any

other reasonable option. Maybe you can safely cut over the median strip

without hurting anyone or damaging your vehicle and escape the snarled

traffic, but it may not be possible. You may be stuck with the situation and

have to deal with it. But as a warrior, you have the skills to do this. You

may be cursing at yourself for not turning off earlier and taking a different route, but you obviously didn't have sufficient information at the

time to see things differently, so what's the point of beating yourself up

now? Again, the skill here is to be able to sit with your emotions and feelings and put space between them and your responses, to dial down the

frequency, intensity, and duration of your responses so they are appropriate for the situation. You don't have to immediately change situations

when you become uncomfortable. You can simply let your reactions and

emotions exist without acting on them; eventually, they will subside or

shift.

Here's another example: A friend of yours calls you up and tells you

to meet at a certain time and place, but doesn't show up and then doesn't

return your phone calls. This person has done this once or twice before.

It would be natural in this situation to feel angry and hurt. It would also

be natural to not like the fact that your friend didn't follow through on

what they said they were going to do, wasting your time. In response, you can feel slighted and immediately assume that your friend has purposely betrayed you, fly into a rage, and do something you later regret,

or you can have patience and weigh the options you consider possible

(dial down the "frequency, intensity, and duration" of your response).

The point is that there are usually options. You also may not know all the

facts. Perhaps your friend didn't show up because of an accident, or perhaps you've known that this is the way your friend is but haven't accepted

it, and keep expecting your friend to change. You don't have to respond

to your friend's behavior immediately. At this moment you may be angry

enough not to care if you destroy the friendship, but this feeling may shift

over time.

Here's a final example: You're sitting in a bar with some friends and

someone you don't know bumps into you, causes your drink to spill,

and then doesn't apologize. Although you think it might be an accident,

you can't be sure, because the person actually laughed a little as they

pushed by you. You may feel angry, disrespected, and insulted that this

individual wouldn't even acknowledge what they had done. So you've

gone from the event (the person bumping you) to feelings (angry, disrespected, insulted). For some warriors, there would be no gap between

their emotional response and further action. They would confront the

person without giving it a thought, and this could immediately lead to

a shouting match or fight. There might be a feeling of enjoyment in

doing this. But is it worth the potential consequences of getting in a

fight, such as possible injury, assault charges, and legal problems? Perhaps the person who bumped you was so drunk and out of it that they

didn't realize what they did. Perhaps they actually did it on purpose and

wanted to pick a fight. However, it may not be in your best interest to act

in this way, no matter how satisfying it might seem to be. One of the key

warrior skills is to know when it's necessary to fight and when a fight can

be avoided. This is the path of the Samurai. This is wisdom. If the other

person throws a punch or pulls a knife or gun on you, then all bets are

off, but until that point, it may be unnecessary or undesirable to respond

with force just because you were bumped and your drink got spilled. A

warrior has nothing to prove.

SKILL 4: LEARN TO MONITOR AND ELIMINATE "SHOULD"

AND RELATED WORDS OR PHRASES

In addition to paying attention to your feelings and emotions, another

skill to learn is to pay attention to how negative thoughts may be contributing to making you feel worse or behave in ways that are detrimental.

Often these happen automatically. Negative thoughts can lead directly to

behaviors and can cause unhealthy physiological changes in your body.

Emotions and thoughts are closely connected. In psychological terms, this

skill is drawn from "cognitive therapy."

The skill is monitoring when you say to yourself: "should," "should

have," "could have," "would have," "shouldn't have," "couldn't have,"

"wouldn't have," "what if," "if only," etc., and pick off each of these words

or phrases with a cleanly targeted sniper round every time they pop up.

These statements are ways we express regret, or punish, criticize, judge,

blame, or place unrealistic expectations on ourselves. They refer to things

in the past that can't be changed, but bother us enough to spend unreasonable amounts of energy on-sometimes a lifetime of energy.

"I should have been able to accomplish that goal" implies that if you

could have accomplished the goal, things would be different (and somehow

better). This diminishes you, sends you on a journey to the land of past

what-ifs, and most important, fails to recognize the innumerable reasons

why you were unable to accomplish the particular goal. Reasons like: more

pressing things that needed to be done; unexpected events happening in

your life; a lack of adequate instruction, training, or resources; an unsupportive family or upbringing; getting sick or injured; a family member get ting sick or injured; someone not doing what they said they would do;

financial difficulties; etc. The "should" statement above implies that I'm

to blame for the outcome-that it's somehow my "fault" that I failed to

accomplish the goal, and that somehow everything would be better if I

had. All of this is pure projection, pure illusion.

Statements like "I shouldn't have done that" or "If only I had done

that differently" express regret and blame. Even if these statements could

be true, so what? It doesn't change anything, and ignores the myriad reasons why you, an imperfect and complex biological mass of cells, did what

you did at that moment. Any more time spent in your thoughts going over

this will only make you feel worse.

Decision-making is a complex task that involves examining what we

feel, analyzing available information, and then acting on this basis. The

problem is that our feelings may be mixed and unclear, and the information is almost certainly incomplete. Additionally, subconscious processes

that aren't in our awareness may also affect the decision.

We can make decisions based on what we think will happen in the

future or how we think we'll feel in the future, which we obviously can't

know. We create stories to define who we are, and we attach some sort of

rationale to whatever decision we make. However, this is rarely, if ever, the

complete story. There are thousands of factors from our environment and

our self (consciously and subconsciously) acting upon us that we can't fully

comprehend, which contribute to the "decision" we think we ultimately

make. Decision-making is incredibly complex and can't be simplified into

any "should have" or "what if" statement.

This type of thinking goes on all the time as a result of combat. "If I

had turned off earlier, we wouldn't have been ambushed." "I should have

been able to tell that the road debris was an IED and stopped the vehicle

in time." In these examples, the warrior is blaming himself for something

that he most certainly had no power to change at that time. These statements express a belief that the warrior had the capacity at the time of the

event to make a different decision, or should have been able to predict

what was about to happen and avert it. It fails to take into consideration

the thousands of things going on in the environment at the moment these events happened. The warrior feels like he failed and is solely to blame for

any bad outcome. Holding onto and shouldering guilt and self-blame can

be a significant part of PTSD and depression.

"Should haves," "would haves," "could haves," "what ifs," etc., come up

all the time in daily life. When you experience reactions to stressful situations, one automatic response is to blame yourself in some way using one

of these statements. "I could have taken a different turn and then I would

have avoided this traffic jam." "I should be able to have better control over

my reactions." "I shouldn't have come to the mall today." "I shouldn't have

gone out with that person last night." "I should have taken the other job."

"I should have spoken up." "I shouldn't have gotten married." These statements simplify a situation that is very complex, and support the feeling/

idea that you had the power to make a different decision. These self-talk

statements provide an illusion of control. They presume that somehow you

could have had the same information that you have right now, and could

have made a different decision at that time in the past. This is obviously

a form of madness that only an organism with a massive cerebral cortex

could come up with.

The more you attack, diminish, or punish yourself with these types

of statements, the more depressed you're likely to become. Depression

can be tied to sleep problems, anxiety, and anger, which is why this is so

important. These self-talk statements affect behavior. The internal monologue of "shoulds" and "what-ifs," connected with emotional reactions, can

lead to behavior that relates to "shoulds" that have nothing to do with

what's going on now. Even if a "should have" or "shouldn't have" relates

to something that happened only a few seconds or minutes ago, that's still

something in the past that can't be changed. Acting on that is a recipe

for disaster. As a warrior, you know that you don't want to act based on a

"should" from a past event; in combat that would obviously be crazy. You

want to act based on what's happening in this moment right now.

This skill is meant to help you recognize every time you say one of

these "should" statements to yourself, and the degree to which you're punishing yourself with them. Think of these thoughts as pop-up targets and

take them out.

SKILL 5: NOTICE YOUR BREATHING

Breathing is the most natural of processes and the simplest route to training your body to be less revved up and more relaxed; it's also a great way to

put space between your physiological/ emotional reactions and behaviors.

Breathing serves to bring in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide and acids

that accumulate as a result of muscle exertion. The breath is naturally slow

and deep when we're relaxed or asleep, and increases when awake. Deep

slow breathing usually involves the diaphragm doing more of the work of

breathing than the chest, with air filling up the lower part of the lungs first.

The diaphragm is the large muscle located at the base of the lungs that

divides the chest from the abdomen. When we exercise, the rate of breathing increases, but generally remains deep to provide the oxygen necessary

to meet the increased demand. However, with high stress or anxiety, paradoxically, breathing may become very shallow, in addition to being rapid,

with muscles in the upper chest (and even neck muscles) doing more of

the work. Rapid and shallow breathing is one of the telltale signs of fear

and anxiety, and is called hyperventilation. Warriors often describe feeling

constricted in their upper chest or neck when they experience high anxiety or anger, which is accompanied by a rapid or pounding heartbeat.

Slowing the breath down, breathing deeper or lower, or simply becoming

aware of how you're breathing are important tools for controlling anxiety.