Autobiography of a Fat Bride (25 page)

But Miss Nancy Sinatra was no such demon, even though I was very hesitant to start up a conversation. In fact, my mouth dried up and my hands started to sweat and I noticed that I was trembling.

I was afraid. Now, I’m not exactly sure what I was afraid of—I mean, she seemed nice and cordial and cheery to everyone else. But I spent the next hour going back and forth—should I say something, should I not say something—and several times I cleared my throat to begin telling Nancy Sinatra Nana’s tale, but then I would chicken out at the last moment.

I just didn’t want to be one of those people, the kind of person who tells an insignificant story to someone they think gives a shit when they couldn’t care less, particularly a famous person. I’m sure that my Nana’s story wasn’t going to be the first time she heard someone tell her about seeing her father singing when he was a skinny little kid; it probably wouldn’t even rank in the first thousand times she’d heard it. In fact, it most likely happened to her on a regular basis, maybe even hourly. Why would she care? Why would Nancy Sinatra give a shit?

And all of a sudden, I realized that I didn’t really need to be concerned with that. I didn’t really need to care if I was boring Nancy Sinatra with an age-old story. Because I wasn’t telling the story for me, and I wasn’t telling the story for her. I was telling it for Nana. I was telling it for the pride Nana carried with her for sixty years, and how seeing Frank Sinatra was one of the most significant moments in her life.

I was going to tell Nancy because Nana never got to tell Frank.

And once I understood that, I cleared my throat and said to Nancy Sinatra, “Ms. Sinatra, I’m sorry to interrupt you,” for which she must have taken me at my word, because she just kept reading the

L.A. Times

real estate section. So I cleared my throat again and said much, much louder, “MS. SINATRA, I’M SORRY TO INTERRUPT YOU,” after which Nancy Sinatra turned and looked at me.

“I’m sorry, I know you’re busy, but this will only take a minute,” I said quickly as she stared at me. “Before the war, my grandparents, Nana and Pop Pop, saw your father singing with Tommy Dorsey at the Brooklyn Paramount, and after the show, my Nana made it a point to look at the marquee and catch his name. And she said to my Pop Pop, ‘Nick, we have to remember that Frank Sinatra kid because he’s Italian and has a beautiful voice.’ She loves that story, and she loved your father.”

“Thank you,” Nancy Sinatra replied with a quick smile before returning to the newspaper.

Honestly, I was surprised. That’s it? That’s all I got for the last hour of torture I had been through? You gotta be kidding, Nancy Sinatra, give me more than that! I screamed in my head. Maybe I hadn’t moved her enough, I decided. Maybe she had heard the story far too often.

I cleared my throat again.

“AND THEN,” I said as I tapped her on the shoulder this time and she turned to look at me again, “and then at my wedding, my Pop Pop, the same one who had seen your father sing, was sick with cancer and had to come in a wheelchair. He couldn’t walk very well by that point, and he had a blanket on his lap because he was cold. I was a little concerned, because he was really looking forward to our special dance later. You know, once my Pop Pop set his mind to something, he didn’t stop until it was done, and he loved to dance to Frank Sinatra records. He was a great dancer. But for the first time, I wasn’t sure if he could pull it off, he wasn’t looking too good. Then, when the time came, and the first notes of Pop’s favorite song—your father singing ‘Fly Me to the Moon’ (oh, do I owe you royalties for that?)—were played, my Pop Pop threw that blanket to the ground and started strutting around like a

Solid Gold

dancer, even I couldn’t keep up with him. Some people started crying, throwing up their hands and saying it was a miracle, that he was not only walking, he was dancing. But I think it was that song. He loved that song and the way your father sang it. We had such a good time out there, he danced and we were laughing, and laughing, and laughing. I really loved my Pop. We had a great time. And as it turned out, that was the last time Pop Pop ever got to dance. We . . . well, we lost him a couple of weeks after that. But at least that last dance was to his favorite song, he really . . . he really loved that song.”

Now, by this point, even I, the girl with the meanest, coldest little black heart in all of the world, had a lump in her throat, and I had to turn my head away quickly, because I was in great danger of Publicly Expressing a Private Emotion. Which is not cool AT ALL. When I looked back a moment later, Nancy Sinatra was looking at me. And then, suddenly, she turned her head and went right back to her newspaper without saying a word.

Nancy Sinatra did not give a shit.

I wasn’t even sure if I cared. I don’t think I did. I mean, I had said what I needed to say, and that was that. It was all I needed to go back to Nana and tell her that I had told Nancy Sinatra her story. Nothing else really mattered. And if Nancy couldn’t give forty seconds of her time to hear a story about people who really loved her father, then I didn’t give a shit, either.

I was at the baggage claim when I saw her again, flanked by her personal assistant and her driver. My suitcase came out immediately, and as I pulled it off the carrier, I turned around and I was face-to-face with her. And that’s when I knew that I was lying, because it turns out that I did give a shit. I did. My grandparents spent decades idolizing Frank Sinatra, watching his movies, buying every record, making sure to watch every single television special, tuning into radio stations that played his music, going back to the Brooklyn Paramount repeatedly to see their favorite new singer. I

totally

gave a shit.

And this was my last chance to say it.

“I’m really sorry that I wasted your time with my dumb little stories,” I said to Nancy Sinatra. “But your dad was really important to my family, and I thought you should know. I thought you might like to hear that.”

She looked startled. She looked very surprised.

“Oh,” she said slowly, and she brought her hand up to her face. “No, no, no, they were lovely. Lovely stories. I just—my daughter is getting married in a few weeks, and we’re playing that same song at her wedding, for my father. And your story . . . it just reminded me of that. It’s . . .

hard,

you know?”

I nodded. I did know. And I also knew, just then, that Nancy Sinatra gave a shit.

“I loved hearing those stories,” she said with a very gentle smile. “Thank you.”

I nodded and I smiled back.

“Thank you,” I said.

Acknowledgments

In lieu of taking everyone out to dinner, I’d like to extend some special thanks. Stop the whining, a free dinner will be forgotten and gone in approximately twelve hours, while your name in print will last a lifetime, or at least for the time it takes for this book to wind up in the outlet stores, when you cheap bastards will finally buy it because you never got the free copy I promised you.

Thanks:

To Jenny Bent, without whom I’d still have a shitty job. A million thanks for a million things—for being the first one in a really long time to believe in me, for the counseling, for listening to me, for letting me talk, for telling me to shut up, and for the biggest prune I will never forget. Oh my God, that was a joke!

To Bruce Tracy, for his patience, direction, support, and friendship, and for letting me keep my voice. Unfortunately, I’ve had editors who are as bad as he is good, and thus, I know enough to appreciate how lucky I am. And I know it.

To my family, for not disowning me after I wiped the shame well dry, for pretending they thought the first book was good, and for not vaporizing my advance by calling in all of my loans. That would have sucked.

Thanks to my ball and chain, who usually just sits and shakes his head. I’m sorry you married a big ole bag of trouble like me, but God gave me big boobs to make up for it. You are the best in the world right now, you know.

To my dad, who foolishly passed out my first book to his friends and colleagues without reading it first, for assaulting warehouse shoppers with it in Costco and harassing them until they bought it, and for teaching me: 1) never buy anything in a dented box; 2) anyone who doesn’t agree with you is an idiot; and 3) anyone who ever fired me was an asshole and dumber than dog shit. Thanks, Dad, and thanks for supporting me when I was jobless and drumming up material for the book, or in other words, “lazy.” But sorry, I still, apparently, cannot hang on to a job in any capacity.

To my mom, who now finally understands that her life is nothing now but a source of material, for being a really good sport, and for keeping her shoe on and not smacking me every time she sees me. You rock, Mom. No, Mom, I didn’t mean it in a dirty way.

To Nick and David, thanks for the material that you have yet to provide, and don’t worry about it, I’ll do for you what Grandma did after she ruined me and pay for your psychotherapy. Fair and square. You are both the best little boys ever and I love you so much. And a very special thanks to your mom for getting Aunt Laurie off of the reproductive hook, so to speak.

To Nana, who makes me laugh, tells me crazy stories, and always surprises me. I have the best Nana ever.

To the Idiot Girls, Jamie, Nikki, Sara, Kate, Sandra, and Krysti, and the Idiot Guy, Jeff—sorry for all the embarrassment I caused you after the last book, but HEY, you got your name in the liner notes and didn’t even have to diddle a guy in the band for it, so STOP COMPLAINING! I am lucky to have you as friends, and even luckier that we’re still friends.

To David Dunton, for being the best friend I only met once, for helping me through some pretty rough spots, for dorking out with me, and for Prime Burger. Forever appreciated, truly.

To Pamela Cannon, for striking the match, and for being one of the coolest chicks I could have ever hoped to know.

To Meg Halverson, Bill Hummel, Theresa Cano, Kathy Murillo, Coni Bourin, Laura K. Smith, Alexa Cassanos, Katie Zug, Sessalee Hensley, Jules Herbert, Donna Passanante, Nina Graybill, Annie Klein, Lisa Dicker, Brent Babb, Curtis Grippe, Brian Griffith, Steve Larson, Patrick Sedillo, Charlie Levy, Jon Kinyon, Jamal Ruhe, Dave Purcell, Monica Reid, Craig Browning, Duane Neff, Amy Silverman, Sonda Andersson-Pappan, Beth Kawasaki, Eric Searleman, Charlie Pabst, Bill Homuth, Sharon Hise, the Public Library Association, the Arizona Library Association, the ladies at the B&N in Fairfax, Ms. Nancy Sinatra, and, of course, bookstores little and big for your help, kindness, support, or for not calling security on me.

And, most important, to Idiot Girls all over the world and everyone who read the last book, wrote a letter, dropped me an e-mail, passed the book on to a friend, confessed that they belonged in the club, stopped by to say hi, or came to a reading: THANK YOU. THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU. The best part is meeting you, laughing with you, and knowing that I’m not the only one. You know what I mean.

You rule.

love, laurie n.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

L

AURIE

N

OTARO

has never written for

Rolling Stone, Esquire, Harper’s, The New Yorker, Truckin’, Lowrider, Coin World, Knives Illustrated, Whispers from Heaven, Dog Fancy, American Logger, Farm Show, Supermodels Unlimited,

or

McSweeney’s

. She lives, and will probably die, in Phoenix, Arizona. Miraculously, this is her second book.

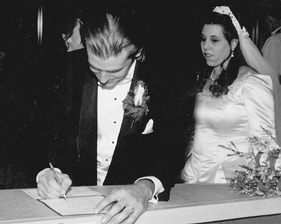

Here she is at her wedding reception, mere minutes after getting married and apparently returning from a satisfying trip to the meatball pyramid. As her lucky new spouse closes the deal by signing the marriage license, his new bride is not only taking that opportunity to dig a meatball particle out of her teeth with her tongue, but has also completely abandoned the effort of sucking her stomach in, never to return.

ALSO BY LAURIE NOTARO

The Idiot Girls’ Action-Adventure Club

Copyright © 2003 by Laurie Notaro

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Villard Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

V

ILLARD

and “V” C

IRCLED

Design are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Notaro, Laurie.

Autobiography of a fat bride: true tales of a pretend adulthood /

Laurie Notaro.

p. cm.

1. Notaro, Laurie. 2. Humorists, American—20th century—Biography.

3. Married women—Humor. I. Title.

PS3614.O785 Z463 2003

814′.6—dc21 2002038086

Villard Books website address:

www.villard.com

eISBN: 978-1-58836-244-5

v3.0