Aunt Effie's Ark (9 page)

Authors: Jack Lasenby

“Oh, là , là !” said Alwyn. “Très posh!”

Jessie asked, “Why did the elephant say, âWe've got a long voyage ahead of us'?” We looked at each other and shook our heads. And then Lizzie asked the question we'd all been too scared to ask.

“Where was the other stuffed head? The one of a man?”

We made a lot of noise scrambling into our bunks and pulling the blankets over our heads. None of us wanted to think about the man's stuffed head, the one we'd all thought of when talking to the leopard.

“Was that his leg the lion was eating?” asked Lizzie so loudly we could all hear.

“I thought it had a foot on itâ”

“Alwyn!” said Marie.

“That was a leg of wildebeeste,” said Peter. “I

particularly

noticed the long hair on the skin.

“Actually,” he said, “the elephant told me the man has a separate room â that's why we didn't meet him. The lion would like to eat the man, so the elephant sticks up for him. Remember the wildlife programmes

we used to watch on telly? They always showed how elephants detest lions.”

We lay in our bunks and nodded. We loved watching the wildlife programmes before the Prime Minister said television was bad for our eyes and closed it down. The only channel she permitted now was one that broadcast parliament when she was speaking. We didn't bother with it: MPs might sound like wild animals, but they're not as interesting to watch.

Next day, after we'd finished our schoolwork, we met the man upstairs. His name was Mr Bulawayo. He was born in Te Awamutu, and his head looked like a cannon-ball with iron curls. He had pointed teeth that he filed sharp on Fridays. “For the weekend,” he said.

“Show us how you sharpen them?” Jessie asked. Mr Bulawayo took out his teeth â they were false â put them in a vice, and rasped away at them with a triangular file. They weren't even made of steel, so we didn't see any sparks. We were disappointed, but the little ones cheered up and ran shrieking when he chased them with the file.

Casey wanted him to bite holes in her ears with his pointed teeth so she could wear earrings, but Daisy said, “The child is far too young to be even thinking of wearing jewellery!” And she whispered loudly, “We don't know if he's a cannibal. Once he tastes blood, he'd be unable to control himself.”

Mr Bulawayo heard her and just laughed. “I don't bite holes in people's ears,” he told Daisy, “because I'm scared I might catch something off them.”

“Hmph!” Daisy wasn't pleased.

“Aunt Effie's a cannibal,” said Jazz. “She ate some

sailors after her ship sank.”

Mr Bulawayo laughed again and said, “Aunt Effie tells some good stories.”

“What happened to your own teeth?” we asked.

“I was doing the pole vault at the Olympic Games, the time they were held in Te Kuiti. I was so nervous, I chewed the end of the pole too hard and wore out my teeth. I had to get false ones and asked the dentist to make them pointed. I was planning to get a job in a circus as âThe Only Cannibal in Captivity'.” Mr

Bulawayo

rolled his dark eyes and snapped his teeth so the little ones backed away.

“The dentist was scared I might bite off his hand while he had it in my mouth, so he didn't make my false teeth pointed enough. That's why I have to file them sharp myself.”

“The first time I went to the Murder House,” Lizzie told Mr Bulawayo, “I bit the dental nurse. She puts on steel gloves when I go now.”

When the circus people found Mr Bulawayo's

cannibal

teeth were false, they sacked him. He got a job collecting wild animals for the Auckland zoo, and met Aunt Effie looking for something to hang on her wall. She didn't like dead stuffed heads, so she asked Mr Bulawayo if he could provide them live.

“The money's good,” he said. “And Aunt Effie pays me extra to stick my own head through the wall. I've found I can give her bad dreams by grinning and

showing

my pointed teeth while she's asleep. It helps pass the time.

“I used to enjoy winking and rolling my eyes at you,” he said to us. “Sometimes I pulled my head in and

closed the little door, so you were never sure whether I was there or not.”

“We thought it was the shadows!”

“After a while,” said Mr Bulawayo, “the wild

animals

' heads grow too big to go through their little doors. Besides, they get sick of standing there so, every two years, I take them back to Africa and hire a new lot. It saves much unpleasantness, especially from the lions.”

“When are you going to Africa again?” asked Lizzie.

“Not for a while,” said Mr Bulawayo. “We changed the wild animals just before Aunt Effie hibernated. Besides, we've got a long voyage ahead.”

It was the second time somebody had said

something

about a long voyage. Peter started to ask what he meant, but Mr Bulawayo's mouth closed. His eyes glazed.

“They look like those brown alleys we won off Mr Jones when he tried to vers us at marbles,” said Jazz. Peter and Marie nodded.

“And his head,” Jazz said. “It looks as if it's stuffed.”

All the wild animals suddenly looked as if they were stuffed. None of them moved or talked. The lion's huge teeth looked made of white plaster, and his tongue was thick with red paint, but we were still scared. As we joined hands and ducked past his door, Alwyn roared at him. Everyone screamed, even Marie and Peter.

Peter locked the stuffed animals' room and opened another door. We found rooms full of giant condors from South America, hummingbirds so small you had to look quickly to see them, rocs so tall we couldn't see up to their heads, dodos, huias, even moas. One room had nothing but witchetty grubs. Another was full of

huhus. There were rooms full of different ants. Some bit us, and we closed their door quickly. And there was a room filled with different kinds of maggots. We could hear them slithering and wriggling, a soft hissing roar.

When David and Victor picked up handfuls of the maggots, Daisy had a fit of the vapours. Marie had to drag her outside and burn some feathers under her nose. Then it was time to get over to the barn and feed the downstairs animals.

We told Hubert about the animals, beetles, maggots, and birds upstairs. “I often wondered,” he said, “why Aunt Effie had all those rooms added on. I thought she was trying to impress the neighbours.”

“They kept mentioning a long voyage,” said Peter.

“Goodness knows what they mean!” said Hubert. “They're only wild animals, after all. Even if they do give themselves airs.” We looked at each other and thought of what the wild animals had said about the downstairs animals.

“What about their food?” asked Hubert.

“It comes down pipes into their stalls. Except for the lion. We think he goes out at night and hunts for his tucker.”

We didn't say to Hubert that the wild animals and insects and birds and beasts upstairs had their own dunnies so their stalls didn't need mucking out each day. We didn't want to embarrass him, besides he mightn't believe us.

“There's one room full of different kinds of lice, Hubert,” said Lizzie, “and there's another full of fleas!” Hubert smiled, and we could see he thought Lizzie was making it up.

That night, as we ate our tea, Peter said to Lizzie, “Perhaps you'd better not tell Hubert everything we see upstairs.”

“Why not?”

“He finds it a bit hard to believe in things he hasn't seen himself.”

“They are so real! I held one of the fleas and it bit me!” cried Lizzie scratching a red lump on the back of her hand.

“We know they're real,” said Peter. “It's just Hubert and the downstairs animals who find it a bit much to believe.” But Lizzie and Jessie and Jared and Casey looked as if they didn't quite know what Peter meant.

“We'll go up the next flight of stairs tomorrow,” he said, “and see what's up there.”

We raced through our schoolwork next day. As we went upstairs, Aunt Effie and the sleeping dogs snored. The stuffed heads hung on the walls, not looking at us. Peter held up a lantern, but we couldn't see Mr Bulawayo.

“I'm sure I wouldn't like a man's head on the wall of my bedroom,” said Daisy.

“Would Mr Bulawayo watch Aunt Effie getting dressed?” asked Lizzie.

“With lovely manners such as his,” said Marie, “I'm sure he'd close his eyes.”

“I still don't think it's very nice,” said Daisy.

We climbed three flights of stairs that day and found a room with a very high ceiling. It was a while before we saw it was full of giraffes looking down at us. One held Jessie up by her collar so she could see out his window.

“It's still raining!” called Jessie. “And the snow's

melting. Did it reach up to your window?”

The giraffe opened his mouth to reply, let go her

collar

, and Jessie dropped. Before she could hit the floor, he'd grabbed her by the collar again. Then all the little ones had to have a turn at being dropped.

Alwyn bellowed at a roomful of hippopotamuses who opened huge mouths and chased him. Peter locked their door just in time.

One dark room had a huge old, white python with milky blind eyes. He lay still, only opening his narrow mouth to flicker his tongue a couple of times, tasting the air.

“Is that you, Mowgli?” he asked, looking at Victor.

“No,” said Peter. “Mowgli died a hundred years ago.” The old python dropped his head. We tiptoed out, and Peter locked the door again.

“Who's Mowgli?”

“A boy in a book by Mr Kipling,” said Peter. “I'll read it to you when we've finished The Wind in the Willows.”

“What do pythons eat?” asked Jared.

“Goats, pigs, monkeys.”

“And small boys,” said Alwyn.

“Did the python eat Mowgli?”

“No. Mowgli spoke the language of all the animals. Kaa, the python, was his friend.”

“Did Mowgli grow up with the animals?”

“He was brought up by wolves.”

“Like the Tattooed Wolf?” asked David.

“Much friendlier than him,” said Peter, but Alwyn howled, “Ooowhooooo!” From behind the door Peter was about to open, we heard something howl back, “Ooowhooooo!”

We scuttled downstairs, locking the doors after us. The stuffed heads in Aunt Effie's bedroom had

disappeared

. “Having their tea,” said Victor.

Peter had a quick look through the peep-hole. “It's still raining,” he said. “And the snow's still melting.”

“Where does all the water go?” asked Lizzie. “From all the rain and the melted snow?”

“Down the drains into the creeks. Down the creeks into the rivers. And down the rivers into the sea.”

“What about the sea? If it's full of rain and melted snow, won't it flood, too?”

“If it did that,” said Peter, “we'd be in trouble. We'd have to find a boat.”

“Aunt Effie said there's sea shells on top of Mount Te Aroha,” said Jared. “That shows it used to be under the sea.”

“If Mount Te Aroha was under, we'd be miles and miles under here,” said Jazz.

“Think of all the water it would take!” Jessie held her hand above her head.

“Listen!” Alwyn said. “Can you hear lapping?” But Marie said he was scaring the little ones and to shut up. Outside it kept raining.

It rained for several months. The snow disappeared. The creek came over its banks. Puddles spread into pools. Pools joined, spread across the paddocks and made lakes. For a few days, the tops of the fence posts showed where the paddocks had been. Then they

disappeared

under the water.

“Did you hear something go bump last night?” Marie said at breakfast. And just then a jug of cream slid off the table. The porridge slopped out of the plates and

on to the cloth.

“Tsk! Tsk! Tsk!” said Daisy.

“Look!” David was staring at his glass. The milk inside it on was on a slant. There was a big bump. A smaller one. Something scraped along the floor. Aunt Effie's enormous kitchen seemed to sway and roll. The backlog in the fireplace settled with a crackle of sparks, and the milk went level in our glasses again.

“I think I know what's happening,” Peter said. We ran to the barn to make sure the stock were all right. We ran back to Aunt Effie's bedroom.

Peter checked up the chimney with his mirror on a stick. Marie looked through the peep-hole. “No sign of the Tattooed Wolf,” they both said. They threw open the steel shutters, and we leaned out the window of Aunt Effie's bedroom. A lake stretched twenty miles from the door of the house to the foot of Mount Te Aroha. We could hear the roar of the Waikato River thirty miles away to the west. East we heard the thunder of a thousand waterfalls tumbling off the Kaimais, into the Waihou River, and flooding the Hauraki Plains.

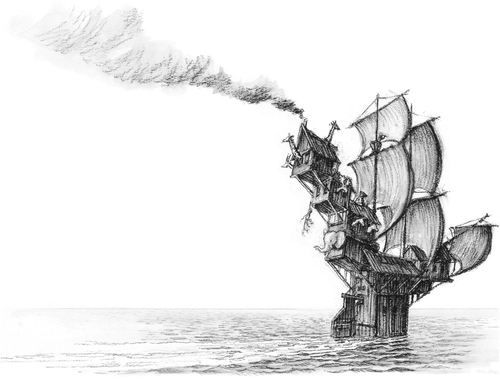

“So that's why Aunt Effie told us to caulk and tar and felt and schenam and sheathe the house and barn,” said Peter. “We're afloat!”

Aunt Effie's house had turned into a huge ship so the barn was now the ship's hold. The wild animals were delighted to find they were on a higher deck than the farm stock. They liked to look down on them and spoke of them as “lower deck types” or “steerage people”.

“Do you want to hurt Hubert's feelings,” Marie asked the snobbish kudu, “and Blossom's, and Rosie's?”

“Yes, we do! Our sense of self-worth depends on having someone to look down upon.” With an

offensive

little laugh, “Heh! Heh! Heh!” the kudu stuck her high-bridged nose in the air. “We,” she smiled, “are upper deck people!”

“Heh! Heh! Heh!” went Alwyn. “Then how do you like having a cabinful of gorillas on the deck above you?” But the kudu and the other wild animals glazed their eyes and turned into lifeless stuffed heads. Even Mr Bulawayo pretended not to hear.

On the deck above the hold, what used to be the kitchen was now called the galley. It still had its huge

fireplace with the maire backlog that never went out, but our bunks were now berths built into the

bulkheads

. Aunt Effie's cabin was on the next deck with the stuffed heads hanging on her bulkheads. Not only was there a cabinful of gorillas above the stuffed heads, but up more companionways we kept finding more decks with more creatures that might have drowned if somebody hadn't provided a dry place.

Alwyn had the time of his life. He meowed at a cabin filled with tigers till they chased him. Peter pulled him out the door just in time, so all Alwyn got was a scratched thumb. He played a tin whistle to a cabinful of rattlesnakes, to make them dance. The rattlesnakes weren't amused and surrounded him with darting tongues, venomous fangs, and rattling tails. Alwyn had to apologise before they would let him go. But he went straight away and pulled faces at the monkeys until they held him down, tickled him till he cried, and tied his hair in knots.

Peter and Marie made him promise to stop

teasing

the animals, but he couldn't help it. The strange thing was â the tigers asked Alwyn to come back and play with them. Then the rattlesnakes begged him to come and play his tin whistle. As for the monkeys, they saved up handfuls of peanuts for him. We couldn't understand that.

Our caulking, felting, schenamming, sheathing, and tarring worked pretty well, but a few leaks came in where somebody whose name we didn't like to say aloud had fired a blunderbuss at the door. Peter melted a billy of tar over the fire, and we teased out some old plough-line, hammered it into the holes made by the

nikauÂ

berries, and tarred it. We split open kerosene tins, and tacked them over the caulking to hold it in place.

“A bit of of a mongrel way to caulk,” said Peter, “from the inside out, but she'll be right!”

“We'll have to give her a name,” said Marie. “Aunt Effie reckons a ship's nothing till she's got a name.”

“Mrs Chapman told us a story at Sunday school,” said Peter. “About an old man with a beard, Mr Noah, who saved all the animals from a flood in a ship called the

Ark

.” We thought we remembered the story, and the name sounded all right to us â except for Daisy.

“I'm almost certain Mr Noah turned his wife to a pillar of salt,” she said. “And then he went on the ran-tan in a town called Sodom or Gomorrah. A nice example to set the little ones!”

“I think you're mixing up Mr Noah with a lot of other people,” said Peter. “The dictionary says an ark is a covered ship for sheltering people and animals during a flood.”

We hung Casey, Lizzie, Jared, and Jessie over the front of the ship by their ankles. They swung a bottle of Aunt Effie's best champagne and smashed it on what we now called the bows.

“We name you Aunt Effie's Ark!” they chorused.

We pulled them back on deck, brushed some broken glass out of their hair, and Daisy told them not to lick their lips.

“If you once acquire the taste for champagne, there's no knowing to what depths you will sink!” she told them. And before we had a feast to celebrate the

naming

of the ship, Daisy insisted they sing her favourite temperance song:

Â

Away, away with rum by gum,Â

With rum by gum with rum by gum!

Away, away with rum, by gum!

That's the song of the Salvation Army!

Â

The little ones chirped the song while Daisy danced, twirled, and smacked her tambourine so hard all the bells fell off, and she burst into tears.

Marie helped Daisy into her bunk. “Here's a nice cup of tea. Now, you have a good lie down.” And she told the little ones, “It's all right, Daisy just got too excited.”

We were grateful now for the haystacks Aunt Effie had insisted we sledge into the barn, and for the crops we'd stored: turnips, swedes, spuds, carrots, parsnips, pumpkins, poorman's oranges, lemons, apples, pears, dried figs and grapes, quinces, almonds, walnuts, chestnuts, dried mushrooms, onions, sides of bacon and ham, barrels of salt beef and pork, and smoked mutton carcasses. We had tier upon tier of barrels of pigeons, pheasants, quail, ducks, black swans, wild geese, pukekos, wekas, and eels â all preserved in their own fat. We had sacks and crates and bins of wheat, maize, barley, oats, lentils, artichokes, dried beans, and split peas. We had lockers filled with jars of marmalade, gooseberry, and strawberry jam. There were more

lockers

filled with peaches, nectarines, and pears preserved in Agee jars. And whenever we wanted honey, we just went to the beehive in what used to be the wall of the

barn but was now the hull of Aunt Effie's Ark. We had a continent of tucker, and we were going to need it!

We had several hundred great barrels of cider. There were also Aunt Effie's hogsheads of wine, rum, whisky, and brandy, as well as her cellar of wines and

champagne

. We tried them but screwed up our noses. The little ones spat it out. Daisy wouldn't try any of it and said, “I'll tell Aunt Effie, as soon as she wakes up, if I see a single one of you under the influence!”

At once, Alwyn hiccuped, crossed his eyes, sang, burped, and fell over. Daisy stared at him and wrote something in her diary. That night, she wrote a couple more sentences in her diary as he tried to sing but got the words twisted around his tongue, as if it was too thick for his mouth. When he fell out of his berth, Daisy wrote a couple more sentences. By the time he lay snoring on the deck, Daisy had written several pages to show Aunt Effie. But, as she closed her diary, Alwyn sprang up, huffed over Daisy, blew out her candle â and all she could smell on his breath was the lemonade we'd had after tea.

“Do you mind!” she said.

“Mind you do!” Alwyn replied. That was another of his exasperating tricks, repeating backwards whatever you said.

At first the keel scraped and bumped against trees, fence posts, and the hill between us and the school. As the flood deepened, we drifted in a circle over Walton, Morrinsville, Ngatea, Thames, and Paeroa. At night, we looked down through the water and saw the

streetlights

still burning, and people sitting at the table,

having

tea in their kitchens. We collided with Mount Te

Aroha, shoved off with long poles, and the wind blew us south. We could see people stranded in cars and buses, waiting for the floods to go down.

“I hope they've got plenty to eat with them,” said Ann.

“The police will organise something,” Marie said.

At Hinuera, halfway between Matamata and Tirau, we floated over the Rotorua Express stopped on the railway lines. No smoke was coming out of its funnel. We looked down through a couple of hundred feet of water and saw the lights still on in the carriages, and the passengers reading papers and playing cards. The guard got wet through every time he ducked from one carriage to another.

“At least he gets a chance to dry out,” said Marie. “It's the driver and the stoker I'm sorry for. See them in the cab? On the footplate? Holding their breath till the flood goes down.”

“How do they go to the dunny?” asked Jared.

“I suppose it's pretty easy,” said Jazz. We looked at each other and laughed, and Daisy went, “Tsk! Tsk! Tsk!”

“At least they'll be warm,” said David.

“No, they'll be cold,” Ann told him. “They'll have to shovel out the wet ashes and light the fire all over again to get up steam, once the water goes down.”

“Listen everyone,” said Peter. “Marie and I've had a talk about You Know Who.” We all knew whom Peter meant by You Know Who. “We haven't seen him since the day he ate our snowman.”

“Poor snowman!” said Casey, and the little ones burst into tears.

“Marie and I think it would be a good idea if we never say You Know Who's name aloud, if we pretend we never saw him, and if we keep our fingers crossed.”

“What about that cabin?” asked Lizzie. “The one Alwyn howled at, and something howled back, â

Ooowhooooo

!' from behind the door.”

“I had a look this morning,” said Marie. “They're just ordinary timber-wolves in there. Quite friendly, really. And they brought their own food; they showed me. They eat only timber, so there's no need to be afraid of them!

“Peter and I think You Know Who probably drowned in the flood. Don't say his name aloud. Keep your

fingers

crossed. And pretend you never saw him. That way, he might never come back.”

We all nodded. It was hard, at first, doing up our

buttons

and brushing our teeth with our fingers crossed, but Marie said we'd get used to it.

When the wind changed, and we drifted north again, Peter said, “We're just getting blown this way and that. We need tools to make masts and sails.”

The little ones had explored more of the ship than the rest of us. They led Peter to the ship's workshop. It had a carpenter's bench and vice, and a blacksmith's forge and anvil. All the tools including cross-cut saws, scissors, pit-saws, pins, marlinspikes, a pedal-driven Singer sewing machine, ropes, fids, blocks, thimbles, timber-jacks, gluts, mauls, sailmaker's palms and needles, all the gear necessary to rig and run a ship hung around the bulkheads. Still keeping their fingers crossed, Peter and Marie sewed a net that we cast over the stern and caught a kauri log floating by.

We hoisted it, using ropes and blocks from the

workshop

.

We built a frame, jacked the log across, and

pit-sawed

it into planks. It was like being back in the bush again, working the kauri, only we sawed some planks a bit crooked because of our fingers being crossed.

We steamed the planks, chamfered, overlapped, and clenched them with copper rivets and washers, and made a clinker-built dinghy. We broke another bottle of Aunt Effie's champagne over its bow and named it The Dog's Hind Leg because of the crooked planks, and because somebody who wouldn't own up put in a couple of ribs upside down. Putting in ribs isn't easy when your fingers are crossed.

We hoisted some long logs on deck, and adzed them into shape for the masts, spars, yards, and booms. It was difficult, but we managed to do it with our fingers crossed.

We remembered how to rig sheerlegs, raised the mizzen-mast towards the stern, and lowered it through holes cut in all the decks till its heel rested on a broad step. We adzed a bowsprit, capped it with greenheart, gammoned and frapped it to the stem with chains and lashings, and snugged it home with a wrapping of cow hides so it wouldn't work and let water into the fo'c'sle.

“Why does it stick up so high?” asked Lizzie.

“That angle's called the steeve. It keeps the headsails and gear out of the water when the ship pitches,” said Peter. “And it gives the jib more lift.”

We rigged a capstan for'ard, ran a wire rope from it through a snatch-block out on the bowsprit, and back to the top of the mainmast.

Ann and Becky had made friends with the cabinful of powerful gorillas. With their help, and the little ones

singing a shanty to give us the time, we heaved on the capstan bars. Down in the bilges, Peter knelt to slip a gold sovereign under the mainmast. The ship rolled over to one side, the mast slipped, and water rushed in. His hand trapped under the mast, Peter was unable to stand as the water rose towards his mouth.

And just at that moment, Ann screamed, “

Something's

sucked all the blood out of one of the sheep!”