Aquarium (2 page)

How was school?

Okay. Mr. Gustafson said next year our grades will matter.

And they don’t now?

No. He said sixth grade doesn’t matter. But seventh grade matters a little bit. He said nothing really matters until eighth grade, but seventh matters a little.

God, where do they find these people? And it’s supposed to be a better school. I had to lie about our address to get you in up there.

I like Mr. Gustafson.

Oh yeah?

He’s funny. He can never find anything. Today we all had to look for one of his books.

Well that’s a great recommendation. I take back everything I said.

Ha, I said, to show I understood. I was looking at all the graffiti, as I usually did. On the rail cars and walls, fences and old buildings. The artists made sequences, like flip books. MOE in bright green and blue, tubular, heading uphill, cresting next in orange and yellow, sinking in gold and red, rising again in blue-black, endless path of the sun. The city something that had to be viewed at speed, but we were always locked in traffic. Five and a half miles from the aquarium to our apartment, but it could take half an hour.

Alaskan Way became East Marginal Way South, which was not as romantic. Hard to dream of going there. If our ride home were a cruise, one of the stops would be Northwest Glacier, which was not ice falling in great slabs but ready-mix concrete, sand, and gravel in great bays and silos chalked white.

We lived next to Boeing Field, an airport but not one used to go anywhere. We were in the flight path of all the test planes that might or might not work. The businesses in our area were the Sawdust Supply, tire centers, Army Navy Surplus, Taco Time, tractor and diaper services, rubber and burgers and lighting systems. On most sides of us, you’d find concrete only, stretching for several miles, no trees, enormous parking lots, used and unused, but you wouldn’t know that when you arrived at our apartment. We looked out on the parking lots of the Transportation Department, endlessly shifting stacks of orange highway cones and barrels, yellow crash barriers, moveable concrete dividers, trucks of all kinds, but the eight buildings of our apartment complex had trees all around and looked as nice as what you’d find in a rich section of town. Subsidized housing with bay windows, pastel colors, pretty wooden fences with latticework. And constantly patrolled by police.

The moment we arrived home, my mother always collapsed on her bed with a big sigh, and she let me collapse on top of her. Cigarette smell in her hair, though she didn’t smoke. Smell of hydraulic fluid. The soft strong mountain of her underneath me.

Bed, she said. I’d like to never leave bed. I love the bed.

Like

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

.

That’s right. We’ll have our heads at opposite ends and just live right here.

I had my hands up under her armpits and my feet slid under her thighs, locked on. No frogfish ever gripped a rock as tightly. This apartment our own aquarium.

Your old mother has a date tonight.

No.

Yeah, sorry salamander.

What time?

Seven. And you’ll need to sleep in your room, in case your mother gets lucky.

You don’t even like them.

I know. That’s usually the case. But who knows. There’s a nice man out there every once in a while.

What’s his name?

Steve. He plays harmonica.

Is that his job?

My mother laughed. You imagine a better world, sweet pea.

How did you meet him?

He works in IT, fixing computer systems, and came to fix something at work. He was around at lunch, playing Summertime on his harmonica, so I ate lunch with him.

Do I get to meet him?

Sure. But we need to have dinner first. What do you want?

Sink dogs?

My mother laughed again. I closed my eyes and rode her back as it rose and fell.

But finally my mother rolled over, as she always did, crushing me to get me to let go. I’d never let go until there was no breath left, then I’d tap out against her shoulder like a Big Time wrestler.

Shower time, she said.

Steve did not look like a computer guy. He was strong, like my mother. Big shoulders. Both of them wearing dark flannel shirts and jeans.

Hello there, he said to me, so cheery I couldn’t help smiling, even though I had planned to be mean to him. You must be Caitlin. I’m Steve.

You play harmonica?

Steve smiled like he had been caught with a secret. He had a dark moustache, and that made him seem like a magician. He pulled a silver harmonica out of his shirt pocket and held it out for me to see.

Play something.

What would you like?

Something fun.

A sea shanty, then, he said in a pirate voice. And we can kick up our heels a bit. He played something from a ship, merry but slow at first, kicking out one toe and then another and turning and speeding up as my mother and I joined, linking our arms, and then he was hopping and frog-legging all around our living room and I was going mad with joy, shouting and my mother shushing me but smiling. An unconscious child-joy that could explode like the sun, and I wanted Steve to stay with us forever.

But they left on their date, left me sweaty and wound up and with nothing to do, pacing around the apartment.

I hated when my mother left me alone. Sometimes I read a book, or watched TV. I wanted a fish tank, but they cost too much and weren’t allowed because they might break and flood the apartment below through the floor and do thousands of dollars in damage. Nothing was alive in our apartment. Bare white walls, low ceilings, bare lights, so lonely when my mother was gone. Time something that nearly stopped. I sat down on the floor against a wall, gray carpet extending, and listened to the wires in the light above. I hadn’t even asked him what his favorite fish was. I asked everyone that.

I

found the old man peering in so close it looked like he was being sucked into the tank. Mouth open and eyes unbelieving.

Handfish, he said. Red handfish. Even less like fins than the frogfish yesterday.

It was a tall narrow tank for sea horses, slim columns of seaweed for them to ride. But at the bottom, in dark rock, was a small cave, pearled around its edges by something mineral in its shine, golden, and guarding the entrance were two pink polka-dotted fish painted red on their lips like children first trying lipstick, exactly what I looked like when I first tried, the red smeared beyond every edge.

Look at him, the old man said. Like he’s leaning out a window.

It was true. Hands painted bright red like the lips, and one of the fish had a hand down on the sill, his other up on the side, as if the cave were a window and he was grabbing on to lean out and take a closer look at us. Small bright red eye, looking wary, and a red nose hung upward on a stalk. Some red whiskers hanging down and red along the tip of his dorsal fin, the ridge of his back, but only these few accents, like a clown wearing a pink nightie. His wife in front of the cave, resting on their purple lawn, strange sea grass.

What are the golden pearls? I asked. Are those eggs?

I see what you mean. I think so. I think they’re guarding eggs, and we look like we might want to steal a couple.

I’ve already had lunch.

The old man laughed. Well, I’ll be sure to let them know.

The handfish opened his mouth, as if he might say something, then closed it again. His elbows flexed at the windowsill.

It doesn’t look like they have scales, I said. They look sweaty.

Up all night, the old man said. Guarding the eggs. Those sea horses are not to be trusted.

We looked up pale green fronds to where the sea horses hung uneasily, pitched unlevel. Bodies of armor assembled in layers, made of something like bone. Not meant to swim.

What’s the point of sea horses? I asked.

The old man stood before them, mouth hung open, as if before his god. I remember he looked like that. So unlike any other adult I knew. His mind wasn’t on a track. He was ready to be surprised and stopped at any moment, ready to see what would happen next, and it could be anything.

I think there’s no answer to that, he finally said. Those are the best questions, the ones that have no answers. I can’t imagine how sea horses could have come to be, and why they have heads like horses on land, why there’d be that symmetry unknown. No horse will ever see a sea horse, or a sea horse a horse, and nothing else might ever have recognized both of them, and even though we do recognize the symmetry now, what’s the point? That’s exactly the right kind of question.

Are they made of bone, all those ridges?

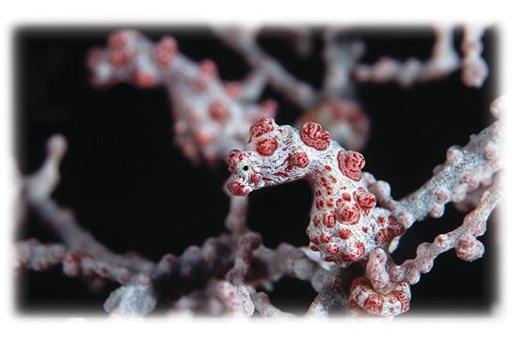

The old man looked at the written descriptions beside the tank. Let’s see. Hey, they’re telling us here to look for pygmy sea horses, on the gorgonian coral. Should be red and white.

Both of us leaned closer. Above the handfish cave were branches of coral dusted pale white with pink warts, but no sea horses.

I don’t see anything, I said. Just coral.

They’re only two centimeters long, he said.

That’s tiny.

And then I saw it. Warts too pink, too bright and clean, not dusted pale. Double wrap of the tiniest tail around a branch, like a miniature snake made of glass. The rounded belly and horse’s head and the smallest black dot of an eye, and covered in these pink mounds just like the coral.

I found one, I said. Then I noticed the shadow beyond, a second pygmy sea horse in exactly the same position, as if all things must be doubled in order to exist.

Where? he asked, but I couldn’t speak.

Ah, he said. I see it now.

A shadow self, not made of flesh. Brittle as the coral. Hanging in a void. Already one of these sea horses was mine, known, and the other was other.

I don’t like the second one, I said. The second one gives me the creeps.

Why? He looks pretty much the same. Or she, or whatever. How can you tell male or female?

I can’t stay here.

Living things made of stone. No movement. And a terrifying loss of scale, the world able to expand and contract. That tiny black pinprick of an eye the only way in, opening to some other larger universe.

I walked away quickly, past tank after tank of pressure magnified and color dimmed, shape distorted. They had speakers for the tanks, and at the moment it was all too much, the parrot fish tearing at coral and shrimp clicking, chittering of penguins. Sound increased beyond measure, the shifting of a few grains of sand like boulders.

I stopped at the largest tank, an entire wall of dim pale blue, reassuring, no sound. Slow movement of sharks, same movement for a hundred million years. The sharks like monks, repetition of days, endless circling, no desire for more but only this movement. Eyes going opaque, no longer needing to see. No fancy clothes but hung in gray with white beneath. Viewed from above, they could look like the ocean floor. Viewed from below, they could look like the sky.

What’s wrong? the old man asked. He was kneeling beside me. He was kind.

I don’t know, I said. And this was true. I had no idea. Just some childhood panic in me, and I think now it was because I had only my mother. I had one person in this world, and she was everything, and somehow that shadow-shape, that doubling in the tank of coral, made me feel how easy she’d be to lose. I had nightmares all the time in which she was underneath a crane in the port and one of those huge containers flying through the air above her. We know fish are always on guard, hiding at the mouth of a cave or in seaweed or clung to coral, trying to look invisible. Their ends could come from anywhere, at any time, a larger mouth out of the dark and all instantly gone. But aren’t we the same? A car accident at any moment, a heart attack, disease, one of those containers coming loose and falling through the sky, my mother below not even looking up, seeing and feeling nothing, just the end.