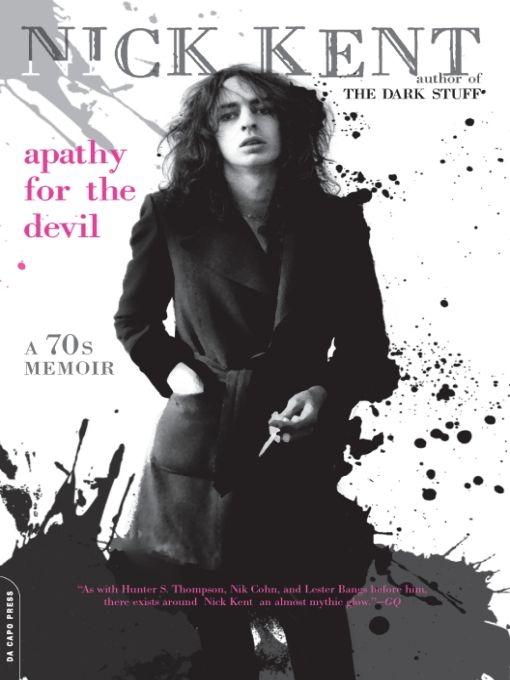

Apathy for the Devil

Table of Contents

Praise for

Apathy for the Devil

Apathy for the Devil

“Fifteen years ago Kent published

The Dark Stuff

, a collection of his finest music journalism, a book to rank alongside Greil Marcus’

Mystery Train

, Nik Cohn’s

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom

and Jon Savage’s

England’s Dreaming

;

Apathy for the Devil

might even be better than that.”

The Dark Stuff

, a collection of his finest music journalism, a book to rank alongside Greil Marcus’

Mystery Train

, Nik Cohn’s

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom

and Jon Savage’s

England’s Dreaming

;

Apathy for the Devil

might even be better than that.”

—DYLAN JONES,

GQ

GQ

“As an eyewitness account of the dangerous excesses of the 1970s rock scene,

Apathy for the Dev

il is in a compulsively readable class of its own. . . . Almost every page contains an anecdotal gem. . . . It’s a miracle, frankly, that Kent survived to tell this tale, but as anybody who romps through

Apathy for the Devil

will agree, we’re all lucky that he did.”

Apathy for the Dev

il is in a compulsively readable class of its own. . . . Almost every page contains an anecdotal gem. . . . It’s a miracle, frankly, that Kent survived to tell this tale, but as anybody who romps through

Apathy for the Devil

will agree, we’re all lucky that he did.”

—ROBERT SANDALL,

Sunday Times

Sunday Times

“While

Apathy for the Devil

adds some backstory to his classic interviews, it’s also a ‘my-drug-hell’ tale dispensed with a bleak wit and brutal candour. . . . Full of fabulous rock tittle-tattle but also some uncomfortable home truths, this is a book for anyone that’s ever read a music magazine from cover to cover but still wanted to know more.”

Apathy for the Devil

adds some backstory to his classic interviews, it’s also a ‘my-drug-hell’ tale dispensed with a bleak wit and brutal candour. . . . Full of fabulous rock tittle-tattle but also some uncomfortable home truths, this is a book for anyone that’s ever read a music magazine from cover to cover but still wanted to know more.”

—MARK BLAKE,

Q

Magazine

Q

Magazine

“Kent tackles his autobiography, as he does his music writing, throwing himself headlong into it and re-experiencing every minute. . . . The magnetic open-heartedness that drew his subjects close lies at the centre of this work, drawing the reader closer too.”

—LOIS WILSON,

Mojo

Mojo

“This is a terrific read imbued with chaos and nihilism, brilliant insights into the lives of Iggy, Bowie, Keith Richards and Lester Bangs, and a lesser-heard take on the cynical, bully-boy tactics of punk—something Kent suffered at the hands of. And if his hazy memory bends the truth at any stage, it only enhances the dark, dangerous picture he paints.”

—CHRIS PARKIN,

Time Out

Time Out

“A blast for every boy and girl who dreamed of being part of the great bacchanalia.”

—AIDAN SMITH, the

Scotsman

Scotsman

“[Kent’s] memory bank of stories is a mile deep. . . . [

Apathy for the Devil

] is worth getting just for the sections about Lou Reed. . . . Kent’s storytelling gifts are considerable and enviable.”

Apathy for the Devil

] is worth getting just for the sections about Lou Reed. . . . Kent’s storytelling gifts are considerable and enviable.”

—JONATHAN O’BRIEN,

Sunday Business Post

Sunday Business Post

“Even if you have an ounce of rock ‘n’ roll in your body, you’ll appreciate these you-couldn’t-make-it-up tales of success, excess and burnout.”

—JOHN LONGBOTTOM,

Rock Sound

Rock Sound

“A tome filled with [Kent’s] untold stories, thousands of them, every one of which a mortal man could dine out on for the rest of his days. But Kent just keeps going, often donating only a single sentence to life-shattering events. It makes his book not just a biography but a thriller; a high-octane chase through a decade’s musical history.”

—SAM WOLFSON,

NME

NME

This book is dedicated to the ones I love - Adrian and Margaret, Laurence and Jimmy

1970

When you get right down to it, the human memory is a deceitful organ to have to rely on. Past reality gets confused with wishful fantasy as the years march on and you can never really guarantee that you’re replaying the unvarnished truth back to yourself. I’ve tried to protect my memories, to keep them pristine and authentic, but it’s been easier said than done.

Music remains the only key that can unlock the past for me in a way that I can inherently trust. A song from the old days strikes up and instantly a film is projected in my head, albeit an unedited one without a linear plot line; just random scenes thrown together to appease my reflective mood of the moment. For example, someone just has to play an early Joni Mitchell track or one of David Crosby’s dreamy ocean songs and their chords of enquiry instantly transport me back to the Brighton of 1969 with its Technicolor skies, pebble-strewn beach and jaunty air of sweetly decaying Regency splendour. I am dimple-faced and lanky and wandering lonely as a clod through its backstreets and arcades looking longingly at the other people in my path: the boys enshrouded in ill-fitting greatcoats and sagebrush beards and the bra-less girls in long skirts sporting curtains of unstyled hair to frame their fresh inquisitive faces.

It was at these girls in particular that my longing looks were

aimed. Direct contact was simply not an option at this juncture of my life. Staring forlornly at their passing forms was the only alternative. This is what happens when you don’t have a sister and have been sidetracked into single-sex schooling systems since the age of eleven: women start to exert a strange and terrible fascination, one born of sexual and romantic frustrations as well as complete ignorance of their emotional agendas and basic thought processes.

aimed. Direct contact was simply not an option at this juncture of my life. Staring forlornly at their passing forms was the only alternative. This is what happens when you don’t have a sister and have been sidetracked into single-sex schooling systems since the age of eleven: women start to exert a strange and terrible fascination, one born of sexual and romantic frustrations as well as complete ignorance of their emotional agendas and basic thought processes.

And so it was that - on December 31st 1969 - I found myself glumly ruminating on my destiny to date. I kept returning to its central dilemma: I had just turned eighteen and yet I had never even been kissed passionately by a lady. It was an ongoing bloody tragedy.

But then it suddenly all changed - just as everyone was counting out the final seconds of the sixties and getting ready to welcome in 1970. I was in a pub in Cardiff when a beautiful woman impulsively grabbed me and forced her beer-caked tongue down my throat. She was a student nurse down from the Valleys with her mates to see the new decade in, she told me giddily. She had long brown hair and wore a beige minidress that showed off her buxom physique to bewitching effect. She smiled at me so seductively our bodies just sank into each other. In a room full of inebriated Welsh people, I let my hands wander over her breasts and buttocks. So this was what the poets were talking about when they invoked the phrase ‘all earthly ecstasy’. Suddenly, a door had opened and the sensual world was mine to embrace.

It was only a fleeting fumble. At 12.05 I unwrapped myself from her perfumed embrace for some thirty seconds in order to seek the whereabouts of a male friend who’d brought me there - only to return and find the same woman locked in an amorous clinch

with a bearded midget. The door to all earthly pleasure had slammed shut on me almost as soon as it had swung open and yet I left the hostelry still giddy with elation. At last I’d been granted my initiation into fleshy desire. I was no longer on the outside looking in, like that cloying song by Little Anthony & the Imperials. And it had all happened just at the exact moment that the seventies had been ushered in to raucous rejoicing. I sensed right there and then that the new decade and I were made for each other.

with a bearded midget. The door to all earthly pleasure had slammed shut on me almost as soon as it had swung open and yet I left the hostelry still giddy with elation. At last I’d been granted my initiation into fleshy desire. I was no longer on the outside looking in, like that cloying song by Little Anthony & the Imperials. And it had all happened just at the exact moment that the seventies had been ushered in to raucous rejoicing. I sensed right there and then that the new decade and I were made for each other.

On the train back to Paddington the next day - I’d been visiting old friends in Cardiff the night before, catching up on their adventures ever since I’d moved almost two years earlier from there to Horsham in Sussex, a mere thirty-mile whistle-stop from London-I felt further compelled to review my sheltered life thus far. Everywhere around me in the new pop counter-culture of Great Britain and elsewhere, young people were gleefully surrendering themselves to states of chemically induced rapture, growing hair from every conceivable pore of their bodies and cultivating sundry grievances against ‘the man’. And yet I was still stuck at home with my parents, who’d brainwashed me into believing that my adult life would be totally hamstrung without the benefits of a full university education and degree. As a result, most of my time was being spent furtively spoon-feeding ancient knowledge into my cranium until it somehow stuck to the walls.

It wasn’t a particularly easy process. I cared not a fig for Martin Luther or his Diet of Worms. But I had three A levels to sit - English, French and History - in May and had to somehow cram all the arcane details of each syllabus into my consciousness in order to get winning results. In retrospect, it wasn’t all a pointless procedure. The French I was studying would hold me in good

stead when I came to live in Paris in my late thirties. My English A-level studies involved poring briefly over the poetry of both Yeats and T. S. Eliot, and both had a forceful impact on my own burgeoning literary aspirations. But then there’d be long mind-numbing sessions of having to grapple with the lofty moral agenda laid out in the collected works of John Milton.

stead when I came to live in Paris in my late thirties. My English A-level studies involved poring briefly over the poetry of both Yeats and T. S. Eliot, and both had a forceful impact on my own burgeoning literary aspirations. But then there’d be long mind-numbing sessions of having to grapple with the lofty moral agenda laid out in the collected works of John Milton.

In

Paradise Lost

Milton spelt it out to the sinners: ‘temperance - the golden mean’ is what humankind needed to adopt as an all-embracing lifestyle if they truly want to get right with God. Wise words, but somewhat wasted on an eighteen-year-old virgin just counting the days before he can catapult himself over to the wild side of life.

Paradise Lost

Milton spelt it out to the sinners: ‘temperance - the golden mean’ is what humankind needed to adopt as an all-embracing lifestyle if they truly want to get right with God. Wise words, but somewhat wasted on an eighteen-year-old virgin just counting the days before he can catapult himself over to the wild side of life.

My father was a great admirer of John Milton also. His all-time favourite poem was Milton’s ‘On His Blindness’. He’d often quote the final line: ‘They also serve who only stand and waite.’ It fitted his overall view of an all-inclusive humanity. My father was a thoughtful man who’d had his young life thrown into turmoil first - as a child - by his own father’s bankruptcy and then - in his early twenties - by having to fight overseas throughout most of the Second World War. He returned in 1945 with the after-effects of undiagnosed malaria and severe rheumatoid arthritis partly instigated from falling out of a moving truck and landing flat on his back on a dirt road in North Africa.

He and my mother, an infant-school teacher born and raised in the North of England, had already met two years earlier in a wartime canteen and had begun an ardent correspondence. They married in 1945 at war’s end and moved into a two-storey house in North London’s Mill Hill area that same year. At first they were told by various doctors that my mother would be unable to conceive, but in April of 1951 she discovered she was pregnant. I

arrived on Christmas Eve of that year after a long and complicated birth. My parents couldn’t believe their good fortune and - rightly sensing that I would be their only offspring - showered me with affection.

arrived on Christmas Eve of that year after a long and complicated birth. My parents couldn’t believe their good fortune and - rightly sensing that I would be their only offspring - showered me with affection.

So often these days people tartly evoke Philip Larkin’s damning lines about family ties - ‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad. / They may not mean to, but they do’ - as if it sums up the whole parental process in one bitter little sound bite. But my parents never fucked me up. They didn’t beat me or abuse me. They loved me and fed me and encouraged me to think about everything, to develop my own value system and stretch my attention span. Above all else, they introduced me from a very early age to the sensation of having one’s senses engulfed by art. Classical music streamed through our living room constantly. Much of it - particularly Beethoven and Richard Wagner-I found unsettlingly bombastic but the works of Debussy and Ravel were also played often and their enchanted melodies wove into my newly emerging brain-span like aural fairy dust. To this day, Debussy’s music can still stimulate within me a sense of inner well-being more profound than anything else I’ve ever known. It is the sound of all that unconditional love pouring down on me as a little child.

My father liked to lose himself in music. He was often in physical pain and relied on its healing properties to keep him emotionally buoyant. He was a professional sound recordist - one of the best in the business. When Sir Winston Churchill - at the very end of his life - was persuaded to read extracts of his memoirs for recorded posterity, my dad was the one invited to Chequers - Churchill’s stately home - to set up the equipment and tape-record the great man’s every faltering utterance. He told

me later that Churchill was in such bad health they had to employ an actor to replicate his gruff tones on certain passages.

me later that Churchill was in such bad health they had to employ an actor to replicate his gruff tones on certain passages.

Other books

At the Heart of the Universe by Samuel Shem, Samuel Shem

Seduction: Book 4 (Strong Young Women Series) by Jordan, Joyce

One night in Daytona (One Night Stands #1) by Ann Grech

Rampage (A Night Fire Novel Book 4) by Watkins, TM

Canyon Song by Gwyneth Atlee

Multiplayer by John C. Brewer

Double Victory by Cheryl Mullenbach

The Furys by James Hanley

Changer (Athanor) by Jane Lindskold