Another Day of Life

Table of Contents

O Lord!

Despite a great many prayers to You we are continually losing our wars. Tomorrow we shall again be fighting a battle that is truly great. With all our might we need Your help and that is why I must tell You something: This battle tomorrow is going to be a serious affair. There will be no place for children. Therefore I must ask You not to send Your Son to help us. Come Yourself.

—the prayer of Koq, leader of the Griquas tribe,

before a battle with the Afrikaners in 1876

We are human beings.

When fear comes, sleep seldom can.

Not everyone can do everything.

The sailor talks about wind; the farmer, about cattle;

the soldier, about wounds.

As long as I breathe, I hope.

Life is vigilance.

There is no life in war.

Man is a wolf to man.

In the gardens of Bellona are born the seeds of death.

The outcomes of battles are always uncertain.

He who can prevail over himself in victory is twice victorious.

You know how to win, Hannibal, but not how to take

advantage of victory!

The only salvation for the conquered: not to expect salvation.

Being conquered, we conquered.

Who was he, who first took up the fearsome swords?

ABBREVIATIONS

FNLA National Front for the Liberation of Angola, led by Holden Roberto and backed by the Western powers and Zaïre.

MPLA Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, led by Agostinho Neto and backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba.

UNITA National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, led by Jonas Savimbi and backed by the Western powers and South Africa

PIDE Portuguese political police

PAP Polish Press Agency

This is a very personal book, about being alone and lost. In

summer 1975 my boss—at the time I was a correspondent for a

press agency—said, “This is your last chance to get to Angola.

How about it?” I always answer yes in such situations. (The reason he asked me the way he did was that a civil war which continues to this day was already under way. Many were convinced that

the country would turn into a hell—and a closed hell at that, in

which everyone would die without any outside help or intervention.) The war had begun in the spring of that year, when the new

rulers of Portugal, after the overthrow of the Salazar dictatorship,

gave Angola and Portugal’s other former colonies the right to

independence. In Angola there were several political parties—

armed to the teeth—doing battle with one another, and each of

these parties wanted to take power at any price (most often, at the

price of their brothers’ blood).

The war these parties waged among themselves was sloppy,

dogged, and cruel. Everyone was everyone’s enemy, and no one

was sure who would meet death. At whose hands, when, and

where. And why. All those who could were fleeing Angola. I was

bent on going there. In Lisbon I convinced the crew of one last Portuguese military aircraft flying to Angola to take me along. More

precisely, I begged them to take me.

The next morning I saw from the window of our descending

plane a motionless white patch surrounded by the sun. It was

Luanda.

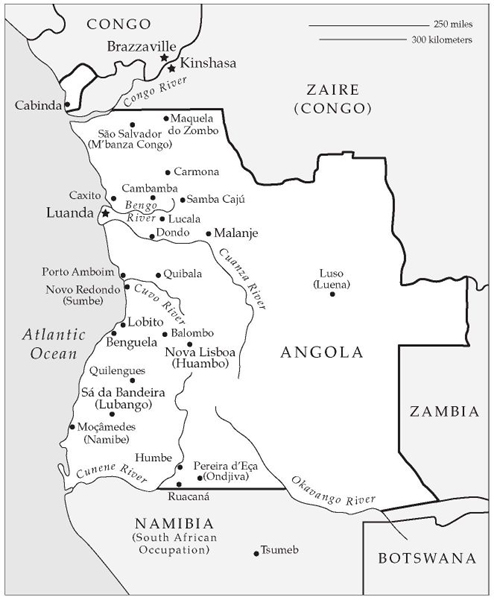

ANGOLA in 1975

We’re Closing Down the City

For three months I lived in Luanda, in the Hotel Tivoli. From my window I had a view of the bay and the port. Offshore stood several freighters under European flags. Their captains maintained radio contact with Europe and they had a better idea of what was happening in Angola than we did—we were imprisoned in a besieged city. When the news circulated around the world that the battle for Luanda was approaching, the ships sailed out to sea and stopped on the edge of the horizon. The last hope of rescue receded with them, since escape by land was impossible, and rumors said that at any moment the enemy would bombard and immobilize the airport. Later it turned out that the date for the attack on Luanda had been changed and the fleet returned to the bay, expecting as always to load cargoes of cotton and coffee.

The movement of these ships was an important source of information for me. When the bay emptied, I began preparing for the worst. I listened, trying to hear if the sound of artillery barrages was approaching. I wondered if there was any truth in what the Portuguese whispered among themselves, that two thousand of Holden Roberto’s soldiers were hiding in the city, waiting only for orders to begin the slaughter. But in the middle of these anxieties the ships sailed back into the bay. In my mind I hailed the sailors I had never met as saviors: it would be quiet for a while.

In the next room lived two old people: Dom Silva, a diamond merchant, and his wife, Dona Esmeralda, who was dying of cancer. She was passing her last days without help or comfort, since the hospitals were closed and the doctors had left. Her body, twisted in pain, was disappearing among a heap of pillows. I was afraid to go into the room. Once I entered to ask if it bothered her when I typed at night. Her thoughts broke free of the pain for a moment, long enough for her to say, “No, Ricardo, I haven’t got enough time left to be bothered by anything.”

Dom Silva paced the corridors for hours. He argued with everyone, cursed the world, carried a chip on his shoulder. He even yelled at blacks, though by this time everybody was treating them politely and one of our neighbors had even got into the habit of stopping Africans he didn’t know from Adam, shaking hands, and bowing low. They thought the war had got to him and hurried away. Dom Silva was waiting for the arrival of Holden Roberto and kept asking me if I knew anything on that score. The sight of the ships sailing away filled him with the keenest joy. He rubbed his hands, straightened up, and showed his false teeth.

Despite the overwhelming heat, Dom Silva always dressed in warm clothes. He had strings of diamonds sewn into the pleats of his suit. Once, in a flush of good humor when it seemed that the FNLA was already at the entrance to the hotel, he showed me a handful of transparent stones that looked like fragments of crushed glass. They were diamonds. Around the hotel it was said that Dom Silva carried half a million dollars on his person. The old man’s heart was torn. He wanted to escape with his riches, but Dona Esmeralda’s illness tied him down. He was afraid that if he didn’t leave immediately someone would report him, and his treasure would be taken away. He never went out in the street. He even wanted to install extra locks, but all the locksmiths had left and there wasn’t a soul in Luanda who could do the job.

Across from me lived a young couple, Arturo and Maria. He was a colonial official and she was a silent blonde, calm, with misty, carnal eyes. They were waiting to leave, but first they had to exchange their Angolan money for Portuguese, and that took weeks because the lines at the banks stretched endlessly. Our cleaning lady, a warm, alert old woman named Dona Cartagina, reported to me in outraged whispers that Arturo and Maria were living in sin. That meant living like blacks, like those atheists from the MPLA. In her scale of values this was the lowest state of degradation and infamy a white person could reach.

Dona Cartagina was also anticipating Holden Roberto’s arrival. She didn’t know where his army was and would ask me secretly for news. She also asked if I was writing good things about the FNLA. I told her I was, enthusiastically. In gratitude she always cleaned my room until it shined, and when there was nothing in town to drink she brought me— from where, I don’t know—a bottle of mineral water.

Maria treated me like a man who was preparing for suicide after I told her that I’d be staying in Luanda until November 11, when Angola was to become independent. In her opinion there wouldn’t be a stone left standing in the city by then. Everyone would die and Luanda would turn into a great burial place inhabited by vultures and hyenas. She urged me to leave quickly. I bet her a bottle of wine that I’d survive and we’d meet in Lisbon, in the elegant Altis Hotel, at five o’clock in the afternoon of November 15. I was late for the rendezvous, but the desk clerk had a note from Maria telling me she had waited, but was leaving for Brazil with Arturo the next day.

The whole Hotel Tivoli was packed to the transoms and resembled our train stations right after the war: jammed with people by turns excited and apathetic, with stacks of shabby bundles tied together with string. It smelled bad everywhere, sour, and a sticky, choking sultriness filled the building. People were sweating from heat and from fear. There was an apocalyptic mood, an expectation of destruction. Somebody brought word that they were going to bomb the city in the night. Somebody else had learned that in their quarters the blacks were sharpening knives and wanted to try them on Portuguese throats. The uprising was to explode at any moment. What uprising? I asked, so I could write it up for Warsaw. Nobody knew exactly. Just an uprising, and we’ll find out what kind of uprising when it hits us.

Rumor exhausted everyone, plucked at nerves, took away the capacity to think. The city lived in an atmosphere of hysteria and trembled with dread. People didn’t know how to cope with the reality that surrounded them, how to interpret it, get used to it. Men gathered in the hotel corridors to hold councils of war. Uninspired pragmatists favored barricading the Tivoli at night. Those with wider horizons and the ability to see things in a global perspective contended that a telegram appealing for intervention ought to be sent to the UN. But, as is the Latin custom, everything ended in argument.

Every evening a plane flew over the city and dropped leaflets. The plane was painted black, with no lights or markings. The leaflets said that Holden Roberto’s army was outside Luanda and would enter the capital soon, perhaps the next day. To facilitate the conquest, the populace was urged to kill all the Russians, Hungarians, and Poles who commanded the MPLA units and were the cause of the whole war and all the misfortunes that had befallen the distressed nation. This happened in September, when in all Angola there was one person from Eastern Europe—me. Gangs from PIDE were prowling the city; they would come to the hotel and ask who was staying there. They acted with impunity—no authorities existed in Luanda—and they wanted to get even for everything, for the revolution in Portugal, for the loss of Angola, for their shattered careers. Every knock at the door could mean the end for me. I tried not to think about it, which is the only thing to do in such a situation.

The PIDE gangs met in the Adão nightclub next to the hotel. It was always dark there; the waiters carried lanterns. The owner of the club, a fat, ruined playboy with swollen lids veiling his bloodshot eyes, took me into his office once. There were shelves built into the walls from floor to ceiling, and on them stood 226 brands of whisky. He took two pistols from his desk drawer and laid them down in front of him.

“I’m going to kill ten communists with these,” he said, “and then I’ll be happy.”

I looked at him, smiled, and waited to see what he would do. Through the door I could hear music and the thugs having a good time with drunken mulatto girls. The fat man put the pistols back in the drawer and slammed it shut. To this day I don’t know why he let me go. He might have been one of those people you meet sometimes who get less of a kick from killing than from knowing that they could have killed but didn’t.

All September I went to bed uncertain about what would happen that night and the following day. Several types whose faces I came to know hung about. We kept running into each other but never exchanged a word. I didn’t know what to do. I decided right off to stay awake—I didn’t want them catching me in my sleep. But in the middle of the night the tension would ease and I’d fall asleep in my clothes, in my shoes, on the big bed that Dona Cartagina had made with such care.

The MPLA couldn’t protect me. They were far away in the African quarters, or even farther away at the front. The European quarter in which I was living was not yet theirs. That’s why I liked going to the front—it was safer there, more familiar. I could make such journeys only rarely, however. Nobody, not even the people from the staff, could define exactly where the front was. There was neither transport nor communications. Solitary little outfits of greenhorn partisans were lost in enormous, treacherous spaces. They moved here and there without plan or thought. Everybody was fighting a private war, everybody was on his own.

Each evening at nine, Warsaw called. The lights of the telex machine at the hotel reception desk came on and the printer typed out the signal:

814251 PAP PL GOOD EVENING PLEASE SEND

or:

WE FINALLY GOT THROUGH

or:

ANYTHING FOR US TODAY? PLS GA GA

I answered:

OK OK MOM SVP

and turned on the tape with the text of the dispatch.

For me, nine o’clock was the high point of the day—a big event repeated each evening. I wrote daily. I wrote out of the most egocentric of motives: I overcame my inertia and depression in order to produce even the briefest dispatch and so maintain contact with Warsaw, because it rescued me from loneliness and the feeling of abandonment. If there was time, I settled down at the telex long before nine. When the light came on I felt like a wanderer in the desert who catches sight of a spring. I tried every trick I could think of to drag out the length of those séances. I described the details of every battle. I asked what the weather was like at home and complained that I had nothing to eat. But in the end came the moment when Warsaw signed off:

GOOD RECEPTION CONTACT TOMORROW 20 HRS GMT TKS BY BY

and the light went out and I was left alone again.

Luanda was not dying the way our Polish cities died in the last war. There were no air raids, there was no “pacification,” no destruction of district after district. There were no cemeteries in the streets and squares. I don’t remember a single fire. The city was dying the way an oasis dies when the well runs dry: it became empty, fell into inanition, passed into oblivion. But that agony would come later; for the moment there was feverish movement everywhere. Everybody was in a hurry, everybody was clearing out. Everyone was trying to catch the next plane to Europe, to America, to anywhere. Portuguese from all over Angola converged on Luanda. Caravans of automobiles loaded down with people and baggage arrived from the most distant corners of the country. The men were unshaven, the woman tousled and rumpled, the children dirty and sleepy. On the way the refugees linked up in long columns and crossed the country that way, since the bigger the group, the safer it was. At first they checked into the Luanda hotels but later, when there were no vacancies, they drove straight to the airport. A nomad city without streets or houses sprang up around the airport. People lived in the open, perpetually soaked because it was always raining. They were living worse now than the blacks in the African quarter that abutted the airport, but they took it apathetically, with dismal resignation, not knowing whom to curse for their fate. Salazar was dead, Caetano had escaped to Brazil, and the government in Lisbon kept changing. The revolution was to blame for everything, they said, because before that it had been peaceful. Now the government had promised the blacks freedom and the blacks had come to blows among themselves, burning and murdering. They aren’t capable of governing. Let me tell you what a black is like, they would say: he gets drunk and sleeps all day. If he can hang some beads on himself he walks around happy. Work? Nobody works here. They live like a hundred years ago. A hundred? A thousand! I’ve seen ones like that, living like a thousand years ago. You ask me who knows what it was like a thousand years ago? Oh, you can tell for sure. Everybody knows what it was like. This country won’t last long. Mobutu will take a hunk of it, the ones to the south will take their cut, and that’s the end of it. If only I could get out this minute. And never lay eyes on it again. I put in forty years of work here. The sweat of my damn brow. Who will give it back to me now? Do you think anybody can start life all over again?

People are sitting on bundles covered with plastic because it’s drizzling. They are meditating, pondering everything. In this abandoned crowd that has been vegetating here for weeks, the spark of revolt sometimes flashes. Women beat up the soldiers designated to maintain order, and men try to hijack a plane to let the world know what despair they’ve been driven to. Nobody knows when they will fly out or in what direction. A cosmic mess prevails. Organization comes hard to the Portuguese, avowed individualists who by nature cannot live in narrow bounds, in community. Pregnant women have priority. Why them? Am I worse because I gave birth six months ago? All right, pregnant women and those with infants have priority. Why them? Am I worse because my son just turned three? Okay, women with children have priority. Huh? And me? Just because I’m a man, am I to be left here to die? So the strongest board the plane and the women with children throw themselves on the tarmac, under the wheels, so the pilot can’t taxi. The army arrives, throws the men off, orders the women aboard, and the women walk up the steps in triumph, like a victorious unit entering a newly conquered city.

Let’s say we fly out the ones whose nerves have been shattered. Beautiful, look no further, because if it hadn’t been for the war, I’d have been in the lunatic asylum long ago. And us in Carmona, we were raided by a band of wild men who took everything, beat us, wanted to shoot us. I’ve been nothing but shakes ever since. I’ll go nuts if I don’t fly out of here at once. My dear fellow, I’ll say no more than this: I’ve lost the fruits of a life’s work. Besides, where we lived in Lumbala two UNITA soldiers grabbed me by the hair and a third poked a gun barrel right in my eye. I consider that sufficient reason to take leave of my senses.