Anne Boleyn's Ghost (11 page)

Read Anne Boleyn's Ghost Online

Authors: Liam Archer

Tags: #Henry VIII, #ghost hand, #queen of england, #Tudor, #anne boleyns ghost, #anne boleyn ghost stories, #henry VIII history, #Hever Castle books, #books, #ghosts, #ghosts of hever castle, #anne boleyn ghost hever castle, #recent sightings of ghosts, #real ghost stories, #ghost stories, #boleyn ghost, #ghost story, #archer liam, #tudor ghosts, #anne boleyns ghost book, #History Boleyn"> , #recent ghost sightings, #Hever books, #ghost history, #interesting ghosts, #kindle, #hever castle ghosts, #henrys six wives

George Boleyn said a far longer and more personal farewell.

You all, and especially you my masters of the Court, that you will trust in God, and not on the vanities of the world, for if I had so done, I think I had been alive as you be now; also I desire you to help to the setting forth of the true word of God; and whereas I am slandered by it, I have been diligent to read it and set it forth truly; but if I had been as diligent to observe it, and done and lived thereafter, as I was to read it and set it forth, I had not come here to, wherefore I beseech you all to be worker and live thereafter, and not to read it and live not thereafter. As for my offences, it cannot prevail you to hear them that I die here for, but I beseech God that I may be an example to you all, and that all you may be made aware by me, and heartily I require you all pray for me, and to forgive me if I have offended you, and I forgive you all, and God save the King.

Sir William Brereton said, ‘The cause whereof I die judge not. But if thou judge, judge thee best.’

And lastly, Sir Francis Weston’s final words were,

‘I had thought to have lived in abomination yet these twenty or thirty years, and then to have made amends.’

Barrels of water were tipped to wash away the thick pools of blood that the ravens had begun feeding on, and the dead were buried, along with their heads, in two adjoined graves, and one not, in the chapel’s graveyard. Everyone that had come to witness the bloody spectacle that day had not cheered when the heads of the others were raised by the headsman. It wasn’t as if they weren’t used to seeing these sorts of gruesome acts carried out, and were horror-struck by it; it was the fact that almost all the condemned men had not confessed their guilt, which was not a good sign that the trials were carried out justly. The public’s suspicion seemed validated, and anger for their King was once again at boiling point.

The Tower’s officials did not want a similar reaction during Anne Boleyn’s execution, so they rearranged it to take place later in the week, and at a different time of day.

Anne tried to set her mind on things less gloomy as the fateful day neared. Peering through her chamber window, she watched the occasional bird fly freely through the air, and gazed at the full moon as it lit up a dense, dark night. She wrote poetry, and sang as she played her lute; and for fleeting seconds, it must have felt, Anne Boleyn infused the air with playful waves of music that traveled far into the lonely depths of the fortress, where surely her brother had been kept.

Poem by Anne Boleyn

Defiled is my name full sore,

Through cruel spite and false report,

That I may say for evermore,

Farwell, my joy! Adieu comfort!

For wrongfully ye judge of me,

Unto my fame a mortal wound,

Say what ye list, it will not be,

Ye seek for that can not be found

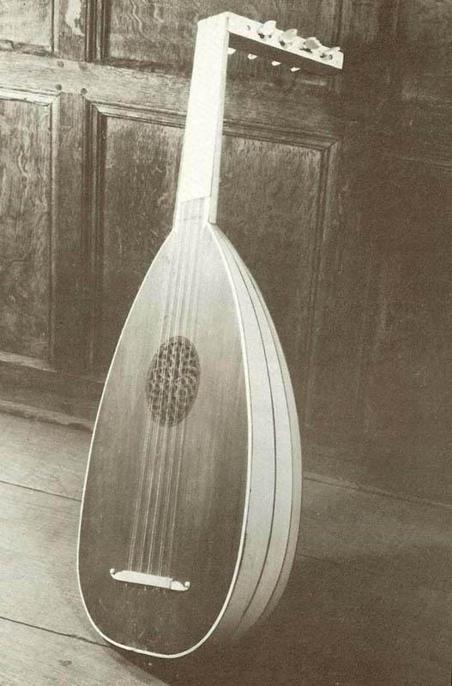

Anne Boleyn’s Lute

On May 16th1536, the Archbidhop of Canterbury arrived at the Tower to provide Anne with absolution, and one other thing: his visit was in part arranged by Henry to have his marriage to Anne Boleyn annuled. He discussed with Anne what the King had asked of him, and a glimmer of hope glittered in the depths of her eyes

–

the King sought to annul their marriage, which would mean her sentence might not be carried out.

That evening Anne had dinner with the Tower’s constable. She told him all about her meeting with the Archbishop, and the prospect she might be set free, if the Archbishop could prove her case. Kingston remained quiet throughout the dinner, feeling it not his place to weigh in on the sensitive subject, but listening all the while with open-ears and an amiable countenance as Anne spoke like someone who had just been given a new lease on life.

Kingston had enjoyed Anne Boleyn’s company, ever since he had first met her at her coronation. But he beared the scars of his profession, and years within the Tower had taught him not to become attached to anyone outside its walls: so often they met their end

here

.

With time running thin, Cranmer dispatched a letter to Henry, and another to Anne, asking them both to appear at his Ecclesiastical Court at Lambeth, to show some reason why the annulment should not be passed.

Next day the Archbishop arrived a little late for the hearing, as his fellows sat waiting, ready to pass the annulment. In Henry’s mind, Anne was finished; and he wasn’t about to give her a chance to haunt his memory right before she died. He wanted her nowhere near him now, so he had appointed Dr. Sampson and Drs. Wotton to appear on their behalf.

The Earl of Oxford and the Duke of Suffolk, as well as other members of the Court listened as Cranmer declared his judgment on the marriage, before providing them with the statement Anne gave him the day before. The Court considered his judgement before giving theirs, and they also agreed that the marriage should be annuled. But, crucially, they concluded that Anne and Henry had been legally married; so her punishment remained unchanged. It was sealed. Anne would be beheaded on the Tower green on May 19th 1536, at eight o’clock in the morning.

*

With one day to go preparations had taken place and everything was ready. A small scaffold had been built, and the famous headsman from Calais, Jean Rombaud, had arrived on time. He was commisioned by the King because Anne had requested for a skilled headsman, and to die by the sword rather than the axe.

Darkness descended upon the Tower and the marching died down as the guards conducted their last exhibition drill. Later that night Anne called for the almoner to provide her with solace. The lone guard shifted once every hour. Each change echoed loudly as their hard-heeled boots tapped ruthlessly against the Tower’s stone, like the inexorable ticking of a clock.

With the hours closing in, thoughts of those final moments went flooding through her mind

–

*

*

*

Morning dawned, and the grey dismal day unveiled itself. Anne dressed in a loose, dark-grey gown of damask and a white coif and black headdress. Not surprisingly, she hadn’t slept the night before, having been apprehensive of the frightening day ahead of her and determined to live every last precious second of her life until she would have it no more.

She asked an attendant to deliver a letter she had written to Kingston; it was a request for him to be with her in such time that she would receive the good Lord.

Kingston respectfully heeded to her wish.

The time of Anne’s execution had been changed that morning as further attempt to catch the public off-guard.

When Kingston arrived at Anne’s chamber she said, ‘I hear I shall not die before noon, and I am very sorry therefore, for I thought I would be dead by this time and past my pain.’

‘There will be little pain,’ he said softly.

Anne knew Kingston well enough by now that his long periods of silence did not unsettle her, and during those final days in the Tower she found it easy to be herself in his presence. ‘I heard say the executioner was very good, and I have a

little

neck,’ she said, putting her hands to it and laughing heartily.

A small smile could just be discerned on Kingston’s deeply lined face.

Anne made her final preparations. She set her eyes upon her reflection for the last time. And at eleven o’clock she followed Kingston through the halls, accompanied by no less than one hundred Yeoman Warders. As they passed the corridor windows, Anne glanced out at the grounds below; three thousand or more crowded men and women stood there.

Once out in the cool, dewy air, the ash-grey sky above seemed to aggrandize her very presence. A light, misty rain was falling through the fog; the sensation of icy water carresing her awoke her soul. The odd raven flew blackly under the darkening sky, or perched high on the wall’s edge, surveying the mass that had gathered below.

For how many people were within the Tower’s walls, the mood remained sombre; under it all, however, the public was yearning to see their captivating Queen one last time.

Anne was led to the green, next to the White Tower. At once the crowd fell silent, as everyone turned magnetically towards her. She walked towards the four-foot high scaffold, which had been designed to minimize her exposure to the crowd, and, alone, stepped up on to the platform where the headsman stood.

Looking like he hadn’t a care in the world, as Anne Boleyn approached the Frenchman, he found himself dumbfounded, and for a few seconds had completely forgotten why he was standing there, in front of so many people.

She observed the executioner impassively, which seemed to bring him back to reality, before turning her eyes to the crowd, looking for familiar faces in the bundle of heads standing motionless before her. Almost all of the King’s Council was there, as well as numerous earls, lords, alderman, merchants, sheriffs, accomplised businessmen and artists. Anne’s father wasn’t there; perhaps he felt guilty for having ever made ties with the King, and was overcome with grief. Her uncle, the Duke, failed to show up. Anne felt relieved that his merciless eyes would not be one of the last things she gazed into. The Duke of Suffolk, who knew her personally, was present, and stood by the other nobles. Thomas Cromwell had, not suprisingly, come to watch the

finale

of his master plan. He lingered amongst the rest, trying hard not to catch Anne’s eye. The Lord Mayor of London, who felt strongly that the trials were of the King’s design, stood high among his fellows, beaming consolingly at Anne as she gazed admiringly back.

The mist slowly began to transform into a gentle rain, becoming heavier and heavier with each solid second that passed. The sky darkened. Everything became still and shadowy. Rain falling hard against the tower’s stone, producing a steady

rush

and a rythmic

rattle,

as if the sky itself had decided to perform a drum roll. The headsman’s sword lay hidden from view; its presence no longer disguised as rain sounded off of the long blade. Anne said good-bye.

Masters, I here humbly submit me to the law as the law hath judged me, as for my offences, I here accuse no man, God knoweth them; I remit them to God, beseeching him to have mercy on my soul, and I beseech Jesu save my soveriegn and master the King, the most godly, noble and gentle Prince that is, and long to reign over you.

She removed her head dress, knelt down on both knees, looked up to the tearful sky and closed her eyes; water falling like heavan’s breath upon her.

…

Jesu Christ I commend my soul

…

The headsman lifted the sword from behind the straw; water ran from the blade in a small torrent. The movements of the sword seemed to resonate an unseen energy that Anne could feel distinctly, though her eyes were closed, as the headsman swung it to and fro in preparation. An ominous drone issued from it.

Raising the sword with both arms, he swung and beheaded her with as much ease, she felt no greater than a rose.

Her headless body fell, blooming a river of blood under the stormy sky. Her lips trembled … her eyes faded … her face turned white as snow.

She was being carried on a wave, completely at its mercy. She was dead … she

was

dead

–

but she could see dark, transient

forms

of men and women standing in front of her. They began to move away from her. They were leaving.

Cannon fire boomed and iron tore through the air over London, signaling to the King that it was all over. The crowd poured out of the Tower, making for the nearest pubs to get dry. The Tower’s officials had failed to prepare a suitable coffin for Anne Boleyn. Her body was disgracefully placed, curled up and on its side, into an empty arrow chest they had managed to find

.

Her ‘coffin’

was then taken to the Tower’s Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula, and buried within. It remains there to this day.