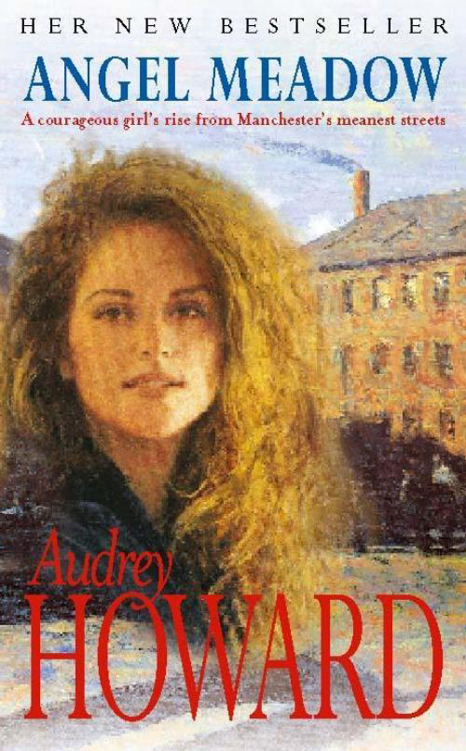

Angel Meadow

|

Audrey Howard

|

Hodder Stoughton (2000)

|

Synopsis

Nancy Brody is different from the rest of the folk in Angel Meadow, the appalling slum where her drunken mother Kitty was a prostitute . . . Only nine years old, Nancy decides to save her sisters Mary and Rose from the workhouse. She gets work for them all at the Monarch Cotton Manufacturing Mill - and then sets out to better herself and her sisters. Saving every penny, working every waking hour, Nancy succeeds, becoming a manufacturer herself. But happiness seems as elusive for Nancy as it was when she was a mistreated child. Though he once said he loved her, Mick O'Rourke has become Nancy's worst enemy, and seems destined to take a terrible revenge on her and her sisters. And Josh Hayes, the man who truly loves Nancy, seems destined to be parted from her.

ANGEL MEADOW

She saw a man, hard, tall, lean, arrogant as men of consequence often are, dressed in the manner of a young gentleman of business . . .

He was perhaps half a head taller than she was and in the tick of a second on the gold watch he wore across his waistcoat, less than a second, as their eyes met there was a flare of recognition, not from a previous meeting but of something in them both.

So here you are, his eyes spoke to hers. I knew you would come one day, and here you are. Yes, I’m here, the answer followed, then the strange moment was over, forgotten as though it had never been and they were just one furious combatant facing another.

ANGEL MEADOW

Audrey Howard

www.hodder.co.uk

Copyright ©1999 by Audrey Howard

The right of Audrey Howard to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in Great Britain in 1999 by Hodder and Stoughton

An Hachette Livre UK Company

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Epub ISBN 978 1 84894 888 4

Book ISBN 978 0 34071 810 0

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

An Hachette Livre UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NWl 3BH

CONTENTS

There is no town in the world where the distance between the rich and the poor is so great or the barrier between them so difficult to be crossed.

Rev Richard Parkinson, 1841,

speaking of Manchester

1

The three little girls crouched in the shadows at the top of the narrow stairs, watching impassively as the brawny man their mother had brought home pulled down his trousers and climbed on top of her. His white buttocks turned to rippling amber in the light from the good fire that he had heaped up carelessly with coal, since he was unconcerned with anyone’s circumstances but his own, before setting about the woman beneath him. Their mother had made no objection to his lavish use of what had taken her so long to earn, obligingly lying down on the rotting wooden floor before the hearth, pulling up her skirt and opening her legs.

For a moment or two he jerked convulsively then, with an exclamation of annoyance, he rose to his knees, looking about him at the bare and comfortless room.

“Ain’t yer got somewhere more comfortable than this, missis?” he asked her. “This floor’s playin’ bloody ’ell wi’ me knees. What’s upstairs? Ain’t yer got no bed?”

He stared up into the darkness of the staircase and the three children shrank back, for some of the men their mother brought home, on seeing them, had lost interest in Mam, stating a preference for a bit of young flesh and, on one occasion, at their mother’s shriek, they had been forced to flee, eluding the man’s grasp by the skin of their teeth as they raced along Church Court and round the corner into Style Street. With their hearts banging in their chests, for they knew exactly what the man had in mind for them, which was what was done to their mother, they had reached the safety of St Michael’s Church where they had hidden for an hour before creeping back to Church Court. Both the man and their mother had gone by then, probably back to the beer house on the corner, the man, it seemed, having made do with Mam since he had no other choice. Mam sported a black eye, a split lip and a swollen cheek when she returned, but she had the few bob she had earned and the girls ate well for the rest of the week.

Mam heaved and wriggled under the man in an effort to please and his attention was caught once more. “It’s warmer ’ere, chuck,” she told him, making a show of great affection, throwing her arms about his neck and drawing him closer to her, at the same time obscenely heaving up her hips and grinding them against his. “An’ we don’t need a bed. See, look what I got fer yer. A lovely little ’ole fer that big cock o’ yours. That’s right, in yer go . . . Eeh, lovely. In’t that lovely?”

The man appeared to agree that indeed that was lovely, for he heaved and grunted for the best part of five minutes before collapsing in a groaning heap on top of their mam. Mam groaned and heaved along with him, though her daughters could see her eyes gleaming in the firelight as they sent their message of comfort and reassurance to them over the man’s shoulder. Whatever she might be their mam always did her best to protect them. She never brought her customers upstairs where, before she had learned better, she had been forced to defend them physically, earning, instead of the few pence she charged for her services, a face that for many days looked like a rainbow pattern of blues and purples and blacks, gradually fading away to green and yellow. Not that it interrupted her trade, for the men she picked up in the streets, the gin-shops and beer houses of Angel Meadow were not concerned with that part of her anatomy! There were men, and there were bad men, she had warned them: men who were content with the bit of comfort and pleasure she could give them; and then there were the others who had funny ways which included a fancy for children. Those sort must be avoided at all costs, though her daughters often wondered how you could tell one from the other until it was too late.

The little girls, huddling together for warmth, waiting for their turn by the fire, were exceedingly thin and indescribably dirty. Their hair was a thick, matted mass of tight curls which, it seemed, had never known the services of a brush; rich brown streaked with a paler brown, and alive with lice which hopped merrily from one strand of hair to another, even from one head to another. Their hands and faces, their necks, their ankles and feet, which were all that could be seen beneath their thin cotton shifts, were a uniform grey, with a thick film of black on the soles of their feet and between each toe. In their ears and the soft, childish creases of their necks was a layer of dirt that had seemingly not been disturbed since the day they were born. In addition to what appeared to be a permanent layer of general filth their fine skin was blotched here and there with what looked like mud.

Downstairs there was a stirring of movement as Mam and her customer groped for their clothing and began to pull themselves together after the enjoyment of their exertions. Mam sat up and fiddled with her tangled hair, giving an arch smile to the man, who did not return it.

“Owt ter drink in this ’ere place?” he asked, throwing himself down into the one chair the room sported, an ancient armchair from which the stuffing leaked and the springs poked. It creaked with his weight, then moaned most piteously as their mam tried to sit on his knee, since she believed in giving value for money and some men liked a bit of a cuddle afterwards.

“Gerrof, yer daft bitch,” he roared, finding her attentions offensive now that his appetites had been satisfied. “D’yer want ter rupture me? Big fat cow like you. Any road, did yer ’ear what I said? Got any gin ’andy? I’ll pay yer for it,” he added and as Mam turned obligingly to the cupboard the child on the stairs saw the crafty look on the man’s face and wanted to cry out to her mother to take care.

The bottle of gin her mother kept for “emergencies”, which could mean anything from the fire going out, the loss of a farthing, or just a cold wet day, all of which depressed her, was produced from its place in the sagging cupboard and within five minutes it was empty, the man taking the last swig. Mam sat on the low stool, her shapeless body slumped over her knees in tiredness, staring vacantly into the fire, and when the man stood up abruptly she jumped, almost falling off the stool.

“Well, I’m off,” he said heartily, reaching for his cap which he had thrown carelessly on to the dilapidated table when he entered the house.

“Right, chuck,” Mam said, her eagerness to be rid of him and huddled up with her daughters on the palliasse upstairs so apparent her daughter wanted to shout to her to be careful. This chap looked as though he might be an awkward bugger and if he was and decided to give her mam a good hiding, which some of her customers did, there was nothing anyone could do about it. Her mam’s trade was frowned upon, even by the hopelessly poor women who lived in Angel Meadow and she’d get no sympathy nor assistance from them next door nor indeed anyone, even if she screamed the place down. There was always someone screaming or giving what for to somebody else in Angel Meadow and no one took much notice. Not even the police constables from the station on St George’s Road.

The man was at the door before Mam knew what he was up to.

“’Ere, don’t forget me money, lad,” she smirked, straightening up from the stool and putting out her hand to steady herself against the chimney breast. She had had a few at the beer house round the corner in Angel Street beside the bottle of gin she had just shared with her customer – whom she had never seen before and whose name she did not know – and was a bit inclined to wobble about, but she recognised a bilker when she saw one. He was trying to edge out of the door without paying her and her with three children to support. There wasn’t a farthing in the house, her last “wages” having gone in the purchase of the bottle of gin, and unless she could get a few bob from somewhere, from this bloke, in fact, who owed her, the kids would have nothing to eat tomorrow.

“What money?”

Mam’s jaw dropped, for though she had been cheated before she had not expected it of this one. Big, rough, his face mottled with drink, he had seemed good-natured enough when she had picked him up in the beer house. He’d treated her to a gin before accepting her offer of a “good time” and had even held her arm as though she were a lady on the short walk home from the beer house.