Angel Confidential

Read Angel Confidential Online

Authors: Mike Ripley

Tags: #london, #fiction, #series, #mike ripley, #angel, #comic crime, #novel, #crime writers, #comedy, #fresh blood, #lovejoy, #critic, #birmingham post, #essex book festival, #religious cult, #religion, #classic cars, #shady, #dark, #aristocrat, #private eye, #detective, #mystery

Â

Â

Â

ANGEL CONFIDENTIAL

Â

Â

Mike Ripley

Â

Â

Â

Â

Telos Publishing Ltd

17 Pendre Avenue, Prestatyn,

Denbighshire LL19 9SH

Â

Digital edition converted and published by

Andrews UK Limited 2010

Â

Angel Confidential

© 1995, 2011 Mike Ripley

Author's introduction © 2011 Mike Ripley

Â

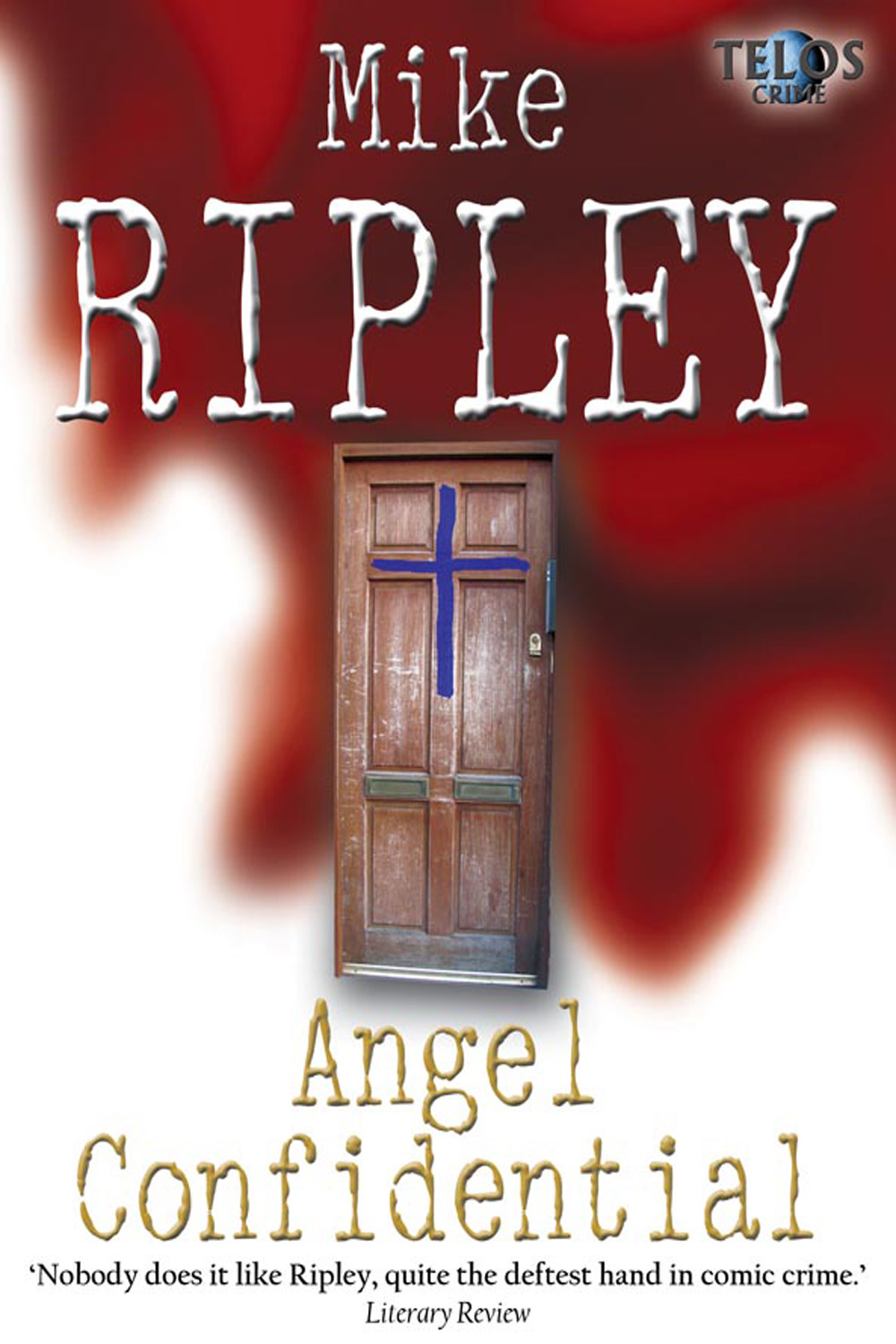

Cover by Gwyn Jeffers, David J Howe

Â

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Â

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

This one is for Guy.

Â

And for all on the collective behind âA Shot in the Dark', because it probably serves them right.

Â

Note: I have taken numerous geographical liberties in this one. Basically just to annoy people.

Â

MR

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Angel Confidential

followed hot on the heels of

Angel City

as the second half of a two-book deal for HarperCollins in their Collins Crime imprint, which had, in a rather casual way, replaced the legendary Collins Crime Club â a brand first established in 1930.

Angel City

had been the most

noir

-ish

Angel tale to date, so I wanted to get back to comedy if not downright farce. Several of the plot strands were ideas that had been bubbling around for a while. I had planned to feature a dodgy religious cult ever since I had met a fellow crime writer whose husband had walked out one day and signed all their possessions (and house) over to one. The fish anaesthetic featured in the sub-plot does exist and was invented by a firm in Norfolk; its launch being one of the first news stories I covered as a trainee journalist. The idea of a gypsy camp in the social services' No-Man's Land where four counties meet and no-one is sure who has responsibility was suggested to me by a Cambridgeshire traffic policeman with several hundred unserved warrants for traffic violations. I also thought it the sort of idea that would have appealed to that other (and far greater) East Anglian crime writer, Margery Allingham, with her sense of the picaresque. The bull-in-a-china-shop image of Angel's black cab Armstrong charging around inside a classic car museum was something I had wanted to shoehorn into a plot for quite a while, because it just seemed the sort of thing Angel â and Armstrong â would do.

So I had the basic framework of comic âset pieces' but I still needed some sort of narrative engine to progress the plot. I remembered a chance remark by another writer (it was either Reginald Hill or Robert Barnard) who asked me:

What sort of a detective is Angel?

What they meant (I think) was that as my series' hero wasn't a policeman or an investigative official of any sort, how did he come to be involved in all those shady goings on?

Just luck, good or bad, I suppose

was probably what I answered, though it got me thinking.

I had always followed the philosophy that Angel could do this âcrime fighting' business basically by being in the wrong place at the wrong time and by falling over clues rather than detecting them. After all, it was funnier that way, wasn't it? I was convinced that Angel, with his high quotient

of streetwise experience (âMore street-cred than wheel-clamps', as someone kindly said) was the ideal detective in his particular world; a world free of responsibilities, paperwork and the need to provide â or even bother to look for â evidence that would stand up in court. Yet as it began to coalesce, the plot of the as-yet untitled Angel #6 seemed to demand a detective who actually detected things. Now the last thing Angel could be was a police detective, so how about a private eye?

Even better; why not team Angel â reluctantly â with an inept private eye, a female private eye? The running gag would be that

he

could do the detecting business standing on his head, but the last thing he wanted was a job with all the attendant responsibilities.

She

desperately wanted to be the responsible, professional, private detective but was actual pretty rubbish at it.

So the character of Veronica Daphne Blugden was born, and she was to team up with the book's

femme fatale

(or one of them) to form the all-female Rudgard & Blugden Confidential Enquiries agency: R & B Investigations.

With Angel acting as unpaid consultant, foil and straight-man to these two would-be private eyes, the title

Angel Eyes

seemed to me to be totally appropriate. At the last minute, though, HarperCollins discovered they had reservations, as the company had already signed up an

Angel Eyes

, by the well-known American thriller writer Eric van Lustbader. Someone had to give way and inevitably it was me, so I suggested

Angel Confidential

for no other reason than I had greatly enjoyed James Ellroy's

LA Confidential

.

(I did get to use the title

Angel Eyes

for a short story in the 1999 anthology

Fresh Blood 3

, a story that was narrated by Veronica Blugden and that, for the first and only time, gave a physical description of Roy Angel, the lad himself.)

My

Confidential

came out in hardback in 1995 and was greeted with over-generous reviews, especially from the right-wing

Sunday Telegraph

and the left-wing

Tribune

. It was just the sort of review coverage I had come to expect, which is a very dangerous state of affairs. As one of my thriller-writing icons, Len Deighton, was later to tell me:

Two things destroy writers â alcohol and praise

.

At the time, however, things seemed to be going swimmingly. Even before the book came out, I was asked by HarperCollins to consider another two-book deal with another, improved advance. Naturally I assumed that paperback sales of

Angel City

were proving healthy â if fact they weren't â and of course I was very flattered, but the truth was I'd had an idea for a book that would fill in the back-story of Angel's life, and the prospect of writing that consumed me to the extent that I could not see the

next

one until I had that one off my chest. There were other considerations too. The television rights to Angel were due to revert to me in 1996 from the production company that had held them for six years and done nothing with them. I knew â or I thought I knew â that Yorkshire TV were interested in buying an option, and HarperCollins were convinced there would be other offers once âwe' had the rights back.

I also still had a day job in London, as Director of Public Relations for the Brewers & Licensed Retailers Association, as the Brewers' Society was now called, which had started to involve frequent trips to Milan (to sell British beer and pubs to the Italians) and to Brussels (to protect British beer and pubs from everyone else in Europe). Back in East Anglia, my family had grown to include a son as well as two daughters and we had moved into a bigger house in a smaller village.

Consequently, rightly or wrongly, I turned down the two-book deal but signed a contract to write one more novel,

Family of Angels

, which was published in 1996 alongside the paperback edition of

Confidential

. I had no idea that it would be my last book for HarperCollins, as not long after publication, the decision was taken, without warning or any chance at negotiation, to drop the series.

And I assumed that that would be that, until other, smaller, publishers began to show an interest in keeping the old rogue in print.

But it was my old friend and former Collins Crime Club stable-mate Walter Satterthwait who provided the key piece of inspiration when he said: âThose two girls in

Angel Confidential

, they were really good characters, you should use them again.'

Walter's advice was sound (for once!) and, as Evelyn Waugh once said: writers should never kill off good characters, as they are so difficult to create.

So R & B Investigations began to play a major part in the rather bonkers career path of Fitzroy Maclean Angel, and fairly soon the inevitable happened and he went to work for them.

I had once tried to end the Angel saga by marrying him off in

That Angel Look

in 1997, but that hadn't worked. Perhaps doing the unthinkable and giving him a regular job would do the trick â¦

Â

Mike Ripley

Colchester, 2010

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Some people would dine out for years on the experience, some might even pay for it, but no self-respecting London taxi driver would do anything but run a mile if somebody jumped in the back of their black Austin FX4S and yelled âFollow that cab!' in their auricular orifice.

To be honest, they wouldn't run a mile. They'd just sit there and turn their head and say âGet real', or âBut the traffic's solid, mate', or âNo fuckin' way', or even possibly something impolite. But let's face it, most wouldn't say auricular orifice in the first place.

I'm not a genuine, licensed, London black cabbie. Sure, I drive a genuine black cab, and if you didn't notice at first that the TAXI sign on the roof was never lit, or that the fare clock had been replaced by the tape-deck of the ICE (In-Cab Entertainment System), then you could be forgiven for making an honest mistake. Especially if you were in an area where cabs are taken for granted as part of the scenery and no-one looks for the lit sign or claims the nearest corner as their territory, arm raised hopefully. Some areas are so over-cabbed that the punter simply dives in, just assuming it's going to be empty.

I was in just such an area, Wimpole Street, and minding my own business. I had just signed off from my private orthodontist, who had finished rebuilding five of my teeth back to smiles-on-stun perfection. As the damage to the molars in question had been sustained in somewhat suspicious circumstances, I had decided to go to a private specialist rather than rely on the National Health Service. Sure enough, the only questions I got asked were about whether I wanted to pay cash or by credit card. It had cost me a packet, but rather than be a burden on the state, I had also fancied the idea of eating steak again while still in my thirties, and for once, I had the money. (Don't ask.)

I had just started up Armstrong's diesel engine and was sitting there listening to it go

thrup, thrup

as it warmed up. I was parked, legally, at the kerb and doing nothing more suspicious than admiring my new teeth in the rear-view mirror. They looked good. Very good. From all angles.

âIf you got âem, bare âem,' I said out loud, and being able to hear each word pronounced clearly for the first time in months just added to the pleasure.

Trying to drink pints of cold lager had been agony for a while, and then an intricate set of braces containing more wire than Steve McQueen could have jumped a motorbike over had made me slur any word with a âch' or a âsh' sound. Directing someone to Chichester had been a bitch.

So there I was, practising my smile and coming close to charming my own pants off when suddenly my personal allocation of daylight was halved by a large female form at the passenger-side window.

Naturally I ignored the shape, hoping it would go away. It didn't. It smacked the back of one hand against the window and brought what sounded like a sledgehammer, but was probably a handbag, down on Armstrong's roof.

âWatch the paint job,' I snarled, reaching over to pull the window down and put my new smile into action for the first time.

âFollow that cab!' bellowed the figure, trying the rear-door handle with one hand and waving vaguely down Wimpole Street with the other.

I got the window down and leaned over. I looked up and let the smile rip.

âNo.'

âBut you're not allowed to refuse a fare,' she blustered.

âOh yes I am,' I smiled.

âThis is urgent.'

âSorry,' I grinned.

âThis' â she fumbled in her handbag â âis official.'

She held out a small leather credit card holder towards me and opened it with trembling fingers.

âAnd that,' I said, still smiling, âis a National Trust membership card.'

The small black wallet withdrew.

âSorry,' she said, then thrust it at me again.

It was a business card this time, one of the sort you can get while-you-wait at a railway station that cost about three quid for 25. This one read:

VERONICA BLUGDEN

Private and Confidential Enquiries

Â

There was a phone number, but I wasn't given time to read it, let alone memorise it. I didn't feel my life was the poorer.

âNow will you follow that cab,

please

?'

she persisted, really agitated by this time and bobbing up and down so I still didn't have clear sight of her. She was also showing not the slightest interest in my new dental work.

âLook, love,' I tried, letting the smile slide into neutral, âI'm not a real taxi.'

She put her head into the window frame and I got my first good look at her. She had a moon of a face (one of Saturn's, I think) and a haircut like a World War II German helmet. The hair was unevenly hennaed auburn and her glasses were large ovals with thick brown frames. From her ears hung plastic earrings in the shape of a pair of balances, the astrological Libra sign. From the neck upwards she had still to register on the fashion scoreboard.

âOh yes you are,' she pouted.

So there was nothing wrong with the glasses prescription-wise. The problem seemed to be her brain.

âNo, I'm not. Armstrong may be a taxi â¦'

âArmstrong who?'

This

was

going to be difficult. I took a deep breath.

âThis vehicle was at one time a licensed Hackney Carriage, what lesser mortals would indeed call a taxi. But

he

is now de-licensed, to, whit: a private car. Do you see a sign saying “For Hire”? Do you see a meter? Do you â¦?'

She wasn't listening, she was staring down Wimpole Street.

âOh fish-hooks! She's gone, and it's all your fault for not taking my fare.' Her face reappeared in the window. âI'll have your number for this.'

She snarled the threat, which meant I got to see her teeth.

Because I was into teeth, I noticed she had smeared lipstick across the front two.

âBe my guest.'

I flipped the central locking off and made to get out. The central locking is one of the other improvements I've made to Armstrong's original sturdy design. Until relatively recently, black cabs in London had not been allowed by law to lock their doors. It must have stemmed from some equal opportunities charter for drunks and muggers. Cabbies, real ones or âmushers', used to have to secure their cab doors with chains and padlocks when they parked them overnight; the only time they were allowed to lock them. If they didn't, odds were the back seat had been occupied by a vagrant or a pair of young lovers who still had parents at home. The back seat and one of the jump seats held down by diagonally stretched legs is just about adequately comfortable if you're passionate enough, and young enough. (So I'm told.)

I walked around the offside of the cab until I was by the boot and pointed down at the paintwork. Armstrong had suffered several paint jobs in his time to cover up the odd scratch, dent, shotgun blast and in one case graffiti, so it was impossible now to tell that he had ever had a Hackney Carriage plate screwed there.

âIf I had a number,' I said cheerfully, âthat's where it would be.'

She looked at me as if I had just beamed down in front of her. She was taller than me, but then she was standing on the pavement and she was wearing high heels, the sort that gave her hell at the back of the ankle so she had to wear elastoplasts where they rubbed. The rest of her was enveloped in a white trench coat, the belt knotted and straining over her left hip.

âI'm on a very important case,'

she hissed, âand now you've messed it up and I won't get another chance.'

I thought for a moment she was going to hit me, but she did something far more unexpected. She stamped her right foot hard on the pavement and began to howl.

It wasn't crying. I know what crying is; I've seen

Casablanca

16 times, once in an Aberdeen oil-riggers' pub at three in the morning. That's crying. This was howling with tears.

The first thing I did was to take a step back from her so that the passers-by on the other side of Wimpole Street, who were already turning to look, could see that we were not in physical contact. Why was I worried? It was me being assaulted.

âNow, calm down, lady, will you?' I tried. I even remembered some of the lessons from the

Safety Body Language for Men

correspondence course I'd taken once (during a postal strike) and leaned back, showing her the palms of my hands. The howling turned into a staccato braying, a fair impersonation of a donkey with its tail trapped in an elevator door.

âAll I'm saying,' I said, trying not to shout, âis that I'm not a cabbie. This is a private car. You can't hire me, it would be illegal. Probably.'

She stopped braying and sobbed twice, catching her breath.

Then she said, clear as a bell, âYou could give me a lift, though.'

âWell. I suppose I could, hypothetically â¦' I said slowly.

Too slowly.

âThat's a fab idea. Shepherd's Bush Green, please.'

Two stars for cuteness, definitely. But âfab'?

âNow wait a minute. I only said could, not would. Shepherd's Bush Green is west and I'm going east, plus at this time of the day I'm going to get stuck in traffic and consequently be late for a very important social engagement this evening.'

Quite what, I hadn't decided yet, but it seemed a reasonable sort of alibi. The sort of argument any reasonable person would accept without too much strife. First mistake; thinking I was dealing with a reasonable person.

âYou did say you would, you did, you did,' she snapped, increasing the volume with each beat and, believe it or not, stamping her foot again.

This was ridiculous. What she needed was another five-year-old to run up and pull her pigtails. I scanned the street in vain. There's never one around when you want one.

âOkay, okay,' I soothed. âCalm down, foot off the pedal. Let's sit inside and we'll negotiate.'

I know I should have just driven off and left her there. But I was in a strangely generous mood. I had time on my hands, some cash in the bank for once and all my teeth back in my mouth, so I was moved to take pity on her. The mood I was in turned out to have a medical name: barking mad.

âGet inside?' she said suspiciously.

âWere you thinking of riding on the roof?' Two minutes ago she was baying at the moon because I said she couldn't get in.

I think she said âHmmm', while weighing up her options, but after no more than half a minute's thought she reached for the door handle and got in. She slid across the back seat as far as she could go, pulling the trench coat around her legs and making sure she was in grabbing distance of the offside door handle. Little did she know that one of the few lessons in the

Safety Body Language for Men

course that had got through had been the one about riding in taxis. I had never known before then that the act of getting into the back of a black London cab was such a sexual minefield, and happy hunting ground for men with the subtlety of approach of a Panzer attack and hands supple enough to count mating snakes. But then again, I don't wear short skirts. Or at least, not in the back of cabs.

I pulled down the jump seat diagonally opposite her and put my hands on my knees where she could see them. I even left the door open a tad, not so much to reassure her but to allow me a quick exit if needed.

âNow, Ms Blugden ... was it?' I don't have a good memory for names and I'd only seen her card for a second or two, but there are some that register quickly.

âIt's Miss, not Ms. I hate Ms.'

Oh, great.

âWhatever. Now, why the scene, the big production number?'

She took a breath deep enough to make her bosom wobble, and I promised myself that if she took out a lace handkerchief to dab away a tear, I'd drive her to the nearest museum and enter her in the Feminist Time-Warp section.

âI'm on assignment,' she said quietly, âa

confidential

assignment that involves ...

surveillance

.'

She said âsurveillance' with the same awe other people reserve for âGood ganga', or âHey, it's unlocked', but I remained unimpressed.

âThe girl I was following went into one of these ... these ⦠houses.' She waved a limp hand at Wimpole Street as if it was to blame. âI'd been following her all day, making notes, and then she came out and she jumped into a taxi. I hadn't expected that. I mean, she came by tube, so I thought she'd go back by tube.'

âTo Shepherd's Bush Green?' I offered helpfully.

âNo, that's where

I

live. I don't know where she lives. That's what I was trying to find out.'

âBut you said you followed her all day. Where did you start?'