Andrew Jackson (51 page)

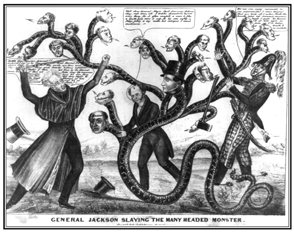

T

he Bank Veto

[LIBRARY OF CONGRESS]

J

ackson vs. Biddle

[LIBRARY OF CONGRESS]

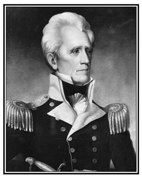

H

ero

[TENNESSEE STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES]

P

lanter

[TENNESSEE STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES]

S

tatesman

[LIBRARY OF CONGRESS]

P

atriarch

[LIBRARY OF CONGRESS]

M

adison didn’t need the reminder, but Jackson’s refusal to follow orders against the settlers made plain that the Tennessean wasn’t an ordinary general. He had his own moral compass, and his popular prestige gave him freedom to chart his own course. Madison could have fired Jackson, but he didn’t want to alienate Jackson’s many followers and perhaps tempt the general into entering the political arena. And he had to acknowledge that much of what Jackson said was true: to uproot the settlers would require sending federal troops against them. Whether or not this would provoke the civil war Jackson predicted, it would certainly be controversial. So Madison backed off. Rather than give Jackson an ultimatum, the president appointed Jackson to a commission to settle the Cherokee claims. If Jackson became responsible for the problem, Madison reasoned, he would have to accept responsibility for the solution. The other advantage of the commission was that it would postpone any difficult decisions till after the 1816 election.

Madison’s strategy did buy him time, and the apparatus of American politics prepared to make James Monroe president. Almost three decades after the constitutional convention of 1787 the system of selecting presidents continued to evolve. Political parties, unrecognized by the framers of the Constitution, had become an accepted feature of the American landscape, except that the Federalist party had essentially self-destructed, leaving the Republicans in control of national politics, with the consequence that whoever won the party’s nomination waltzed to election. That nomination lay in the hands of the party caucus, which was to say the Republican members of Congress gathered in unofficial and secret session. This hardly comported with the increasingly democratic spirit of the age, besides tilting the field in the direction of Washington insiders. Virginia, abutting the federal district and claiming the largest Republican delegation, had an apparent lock on the presidency. Of seven presidential terms thus far, six had gone to Virginians, with Monroe positioned to claim two more.

The situation prompted criticism. Aaron Burr wasn’t unbiased in viewing Virginians, but he articulated the opinions of many when he analyzed the approaching election season. “A congressional caucus will, in the course of the ensuing month, nominate James Monroe for President of the United States, and will call on all good republicans to support the nomination,” Burr told his son-in-law, Joseph Alston, who happened to be governor of South Carolina. “Whether we consider the measure itself, the character and talents of the man, or the state whence he comes, this nomination is equally exceptional and odious. I have often heard your opinion of these congressional nominations. They are hostile to all freedom and independence of suffrage. A certain junto of actual and factitious Virginians, having had possession of the government for twenty-four years, consider the United States as their property, and, by bawling ‘Support the Administration,’ have so long succeeded in duping the republican public.” Burr urged Alston to defy the party leadership. “The moment is extremely auspicious for breaking down this degrading system. The best citizens of our country acknowledge the feebleness of our administration. They acknowledge that offices are bestowed merely to preserve power, and without the smallest regard to fitness.”

Burr had just the man for the moment. It certainly wasn’t Monroe, who, besides being the beneficiary of the system, was “naturally dull and stupid, extremely illiterate, indecisive to a degree that would be incredible to one who did not know him, pusillanimous, and, of course, hypocritical.” Burr instead proposed someone who was everything Monroe wasn’t. “If, then, there be a man in the United States of firmness and decision, and having standing enough to afford even a hope of success, it is your duty to hold him up to public view. That man is

Andrew Jackson

. Nothing is wanting but a respectable nomination, made before the proclamation of the Virginia caucus, and

Jackson’s

success is inevitable.”

For obvious reasons of history, Burr couldn’t effectively forward Jackson’s candidacy himself, which was why he urged Alston to do so. But Burr’s letter arrived at just the wrong time. Alston’s wife, Burr’s daughter, Theodosia, had recently died, and the governor was prostrate from grief and kindred maladies. “I fully coincide with you in sentiment,” he told Burr, “but the spirit, the energy, the health necessary to give practical effect to sentiment, are all gone. I feel too much alone, too entirely unconnected with the world, to take much interest in any thing.”

Alston never recovered from his broken heart, and he died a short while later, leaving Jackson and the rest of the country to watch the election of 1816 unfold as Madison and the Republican leadership desired. But the many people who were hardly more enthusiastic than Burr about Monroe and the Virginians asked whether America’s manner of choosing presidents might someday be different.

E

arly September of that election year found Jackson at the Chickasaw council house in northern Mississippi hammering out a treaty with the Cherokees over the lands in dispute with the Tennesseans, and in dispute between the Tennesseans and the federal government. Jackson was still angry at William Crawford. “If all influence but the native Indian was out of the way,” he told Robert Butler, his aide, “we would have but little trouble. But a letter from the Secretary of War to the [federal Indian] agent, which had been received and read to the nation in council before our arrival, has done much mischief.”

With no little effort, Jackson and his fellow commissioners, Jesse Franklin and David Meriwether, managed to undo the mischief and reach an agreement. The Cherokees and Chickasaws surrendered title to the lands in dispute in exchange for a series of monetary payments. “We experienced some difficulty with the Chickasaws,” Jackson told Monroe, by now president in all but name. The Chickasaws referred to a treaty negotiated with President Washington, which bound the United States to prevent intrusions upon the land in question. Jackson rejected the treaty as invalid. “The fact was that both President Washington and the present secretary of war were imposed on by false representation, as neither the Chickasaws or Cherokees had any right to the territory, as the testimony will show it being in the possession of the Creeks at that time and continued to be possessed by them until we conquered the territory in the fall 1813 and spring 1814.” For Jackson, conquest provided the clearest title, which since Horseshoe Bend belonged to the United States. Yet he was willing to pay the Cherokees and Chickasaws to end the confusion. “All these conflicting claims are happily accommodated by the late treaties with those tribes at the moderate premium of 180,000 dollars payable in ten years.”

He judged the result well worth the expense. “This territory, added to the Creek cession, opens an avenue to the defence of the lower country, in a political point of view incalculable. We will now have good roads, well supplied by the industry of our own citizens, and our frontier defended by a strong population.”

W

hen Jackson learned, about this time, that Crawford was leaving the War Department, he took the opportunity to offer Monroe some advice regarding a successor. He had heard good things about William Drayton of South Carolina, he said. “He is a man of nice principles of honor and honesty, a man of military experience and pride.” He was also a Federalist, but not one of those secessionists from New England. “The moment his country was threatened, he abandoned private ease and a lucrative practice for the tented fields. Such a man as this, it is not material by what name he is called; he will always act as a true American.” For this reason Monroe ought to consider him seriously.